My Obsession with Egypt’s Greatest Voice Ahmed Adaweya

Guest contributor Gary Sullivan traces his decades-long journey into the raw emotion, street-level storytelling, and political undertones of Ahmed Adaweya.

I was a latecomer to Ahmed Adaweya. I first encountered Arabic music in 1996 when I stumbled upon Daff & Raff, a short-lived book and music store in Cambridge’s Harvard Square run by Joseph Adi and Mona Fayad, and walked out with a CD by Farid & Asmahan. Why would I do that, given that I neither speak nor read Arabic? The simplest answer is that a series of recent prior events had completely rewired my worldview.

Earlier that year friends took me to my first Bollywood film, I heard Pakistani Sufi singer Abeeda Parveen on a local college radio station, had randomly picked up a cassette from the dollar bin by Turkish arabesque singer İbrahim Tatlıses and, a week later, a bought a Persian classical music cassette from a restaurant after a particularly wonderful dinner. Just one of these experiences would have been significantly mind- and ear-altering, but four in a row?

I had studied western music composition in college, and the rapid-fire exposure to several other modalities was a revelation. If I had walked into Daff & Raff 12 months earlier, I probably would have glanced at the blur of Arabic CDs and moved on. But instead of registering the collection as opaque, my recent experiences nudged me to take a chance. When I got home and listened to the new CD, Asmahan’s ‘Ya Habibi Taala’ proved the final straw. I abandoned English-language popular music and devoted the next few decades trying to get my ears around what everyone else was doing.

When I moved to Brooklyn, New York, in 1997, I quickly realized that if you walked into an immigrant-run bodega or deli, there was a good chance they were selling cassettes or CDs from their previous homelands. I spent almost every weekend riding my bike or taking the train out to neighbourhoods across my home borough and deep into Manhattan, the Bronx and Queens, amassing a sizable yet affordable collection of international music. I became friendly with store owners and cashiers, many of whom loved to provide recommendations. Not everyone, however, understood why I kept coming into their store. A woman once asked me, when I brought a handful of Oum Kalthoum CDs up to the counter, if I understood Arabic. When I shook my head, she looked perplexed. “Why do you like her, if you can’t understand the poetry?” I tried to explain how Oum Kalthoum’s masterful voice and the sweeping orchestra in which she wrapped it had a strong visceral impact on me, but I don’t think I cobbled together the right words to get my experience across. She looked sorry for me.

Not everyone, however, understood why I kept coming into their store. A woman once asked me, when I brought a handful of Oum Kalthoum CDs up to the counter, if I understood Arabic. When I shook my head, she looked perplexed. “Why do you like her, if you can’t understand the poetry?” I tried to explain how Oum Kalthoum’s masterful voice and the sweeping orchestra in which she wrapped it had a strong visceral impact on me, but I don’t think I cobbled together the right words to get my experience across. She looked sorry for me.

It wasn’t until I moved from Brooklyn to Queens in 2010 that I finally heard Ahmed Adaweya. I still remember everything about that day. It was late autumn, a slight chill in the air, and I poked my head into the Nile Deli on Steinway Street, a 10-minute walk from my apartment. I noticed his ‘Very Best of’ CD on the rack amidst a bunch of other titles. I didn’t recognize the affable chubby guy in sunglasses on the cover, but I was always on the lookout for artists I hadn’t yet heard of, so I picked it up.

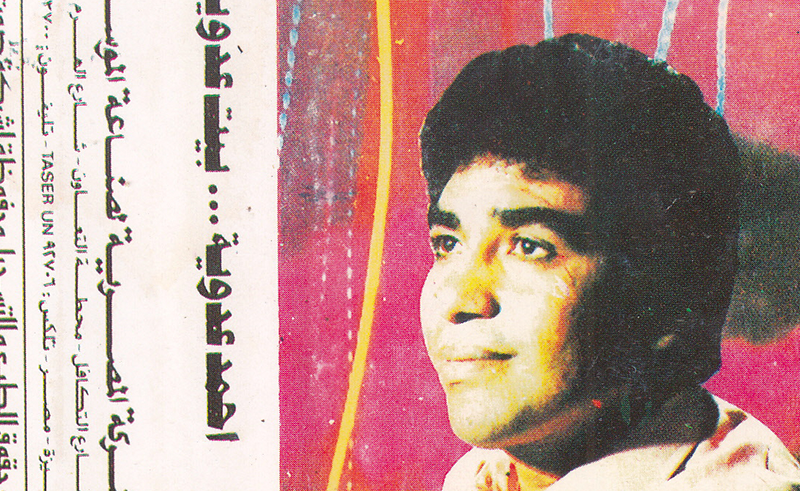

When I got home, popped the CD into my player and pressed PLAY, I was immediately taken aback. The driving drum, splashy tambourine, and warbly trumpet opening ‘El Sah El Dah Embo’ sounded more pared-down, more present-felling, and groovier than I was expecting. The increasingly complex interplay between Adaweya’s voice, his rising emotion, and the sparse instrumentation was on another level.

It was the sixth track, ‘Bint El Sultan’, that completely blew my mind. The incredible slow-burning instrumentation was immediately arresting, and as Adaweya painfully stumbled through the line, “Rabtin ala albued wala ragaeayn tanaa rahu alhabayib,” the hair on the back of my neck stood up and tears began streaming down my face. Again, I don’t know Arabic. But you don’t need to know Arabic to feel that his voice is embodying the raw energy of lovers bound together by an untraversable distance as persistent and totalising as their desire. How was it that this once-in-a-generation, maybe once-in-a-century voice had eluded me all these years? I spent the next decade-and-a-half scouring the internet to collect everything by Adaweya on cassette, CD, and eventually vinyl. As my collection grew and my research deepened, I realised that I was sitting on a couple of recordings not available to hear anywhere online. It also became clear that several of the dates associated with his cassette releases were simply wrong - sometimes off by as much as a decade. I read everything available online and in print about his art, history and impact.

I spent the next decade-and-a-half scouring the internet to collect everything by Adaweya on cassette, CD, and eventually vinyl. As my collection grew and my research deepened, I realised that I was sitting on a couple of recordings not available to hear anywhere online. It also became clear that several of the dates associated with his cassette releases were simply wrong - sometimes off by as much as a decade. I read everything available online and in print about his art, history and impact.

What Egyptians know on first listen - his focus on class and politics, his references to recent events, and his colloquial wordplay and humour - takes time for me to put together, and I’m never sure I have it even close to right, although there is never any denying the power of his voice nor the brilliance of the composers and musicians who gave his voice its platform. The more I learned about Adaweya, the more a doorway into the world of his influencers and collaborators opened. I began to find and listen for the first time to recordings by Mohamed Taha, Shafiq Galal, Abu Draa, al-Rayyis Bira, Mohamed Rushdi, and many others who had been invisible to me prior to digging into Adaweya.

The harder door for me to open has been, simply, what he’s on about. Google’s translation app is bad with Arabic, and even worse with Arabic song lyrics. I do have a sense, from the few English-language accounts of his early hits, that some of his lyrics, while seemingly about everyday street-level situations, might actually be about significant national events - ‘Salamitha Oum Hassan’, for instance, which many interpret to be about getting over the humiliation of Egypt’s 1967.

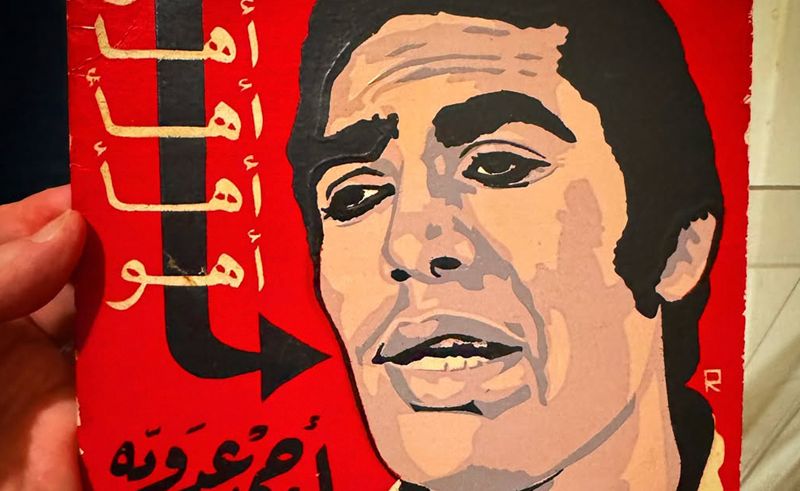

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing, and I find myself looking for hidden meanings everywhere in Adaweya’s body of work. For instance, I’ve found that looking up significant events in Egypt the year of a particular Adaweya release sometimes seems to suggest correlations: Is the title of his 1978 cassette, ‘Salam Murabae’ (‘Peace Square’) an oblique reference to the Camp David Accords of the same year? Is the track ‘6/6’ from 1981’s ‘Ahom…Ahom…Ahom…’ a reference to the failed military coup in June (the sixth month) of that year, and Sadat’s ultimate assassination on the sixth of October? While I know a few people familiar with Egyptian history and the language and even a couple who listen to Adaweya’s music, I can’t run to them every time I’m trying to figure out if a song is about simple lust or complex politics. At best, I’m going to alienate them with my constant stream of questions; at worst, they’re going to think of me as a kind of conspiracy theorist.

While I know a few people familiar with Egyptian history and the language and even a couple who listen to Adaweya’s music, I can’t run to them every time I’m trying to figure out if a song is about simple lust or complex politics. At best, I’m going to alienate them with my constant stream of questions; at worst, they’re going to think of me as a kind of conspiracy theorist.

The frustration of trying to sort out the meaning and cultural significance of his lyrics and to properly date his releases prompted me in May of 2024 to launch a blog: What’s so funny about Ahmed Adaweya? The idea was to create a space that honoured not just the singer but all those - as many as I could account for - who helped make him who he was. I also wanted to establish a more complete and reliable discography than Wikipedia or even Discogs. But, really, my hope is that friends and strangers who visit the blog may begin to offer insight into the meaning of the many songs I’m struggling with.

While I was writing and uploading the first posts, I learned of the passing of Wanisa Ahmed Atef, or Nousa, Adaweya’s wife since 1976. (They would have celebrated their 50th anniversary next year). Months later, word of Adaweya’s passing on December 29th came to me through an Instagram post by the Egyptian-Canadian musician Sam Shalabi, who reminisced about his first hearing the singer:

“… in the first 30 seconds my world was changed … the music struck me like an avalanche—it was as wild, tight and out of control as the best punk rock … and Adaweya’s voice … one of the greatest singers ever … full of panic, sex, humour and a virtuosic intensity I’d never heard anywhere. THIS was the music that connected everything I loved about Punk, Noise, Psychedelia to my Egyptian roots.”

I share Shalabi’s sense of Adaweya as thoroughly punk in attitude - and would add hip-hop to that equation. Hearing that the great singer had passed, I was heartbroken, not really sure how to process the fact that someone I had come to sense was an eternally existing presence in the fabric of Egyptian life and culture was actually gone. He was my favourite living singer. It baffles me that an artist as popular, influential and undeniably gifted as Adaweya should be this unknown outside of his home country, and that even within Egypt’s borders, his bio and output is clouded by rumors, gaps and inaccuracies. I plan to continue with the blog, hoping to set as much of the discography straight as possible, and - if possible - to inspire others to dig even deeper into his life, art and enduring influence.

Trending This Month

-

Jan 29, 2026