What Lagos Taught Me About the Fastest Growing Genre on Earth

A week in Nigeria with Spotify’s music expedition, tracing Afrobeats from Fela’s revolution to the Mavin machine shaping its global future.

Whenever I travel, I like to eavesdrop on a country’s musical zeitgeist. This usually happens filtered through a drip. A trumpet player tailing me down a Mexico City street with unsolicited mariachi. 142 bpm techno on a night (morning) in Berlin; or a friend dating the lead singer of an indie band who convinces me to see him “perform” (shout) songs about tracksuits in an East London pub. It’s a surface level understanding of the musical nuances of the place. It’s what the RL algorithm is telling you the nation’s sound is, the musical equivalent of a Youtube ‘best’ search. But why do mariachi dress like bullfighters and swing to that rhythm? How did Berlin become techno’s Vatican And also, come to think of it, why did I agree to go to that pub?

Last month I got the chance to dive deep into the cultural fabric of one of the most musically rich countries on the continent. Nigeria. Timed with the opening of Spotify’s Lagos pop up venue, Greasy Tunes, Spotify’s ‘Afrobeats: Culture in Motion’ was “music tourism” for people who prefer liner notes to landmarks: a week-long excavation of the roots, people and machinery behind a genre that’s become the country’s biggest cultural export since Jay-Jay Okocha’s step-overs.

But you can’t talk about Nigerian music without starting with Fela Kuti, the man who built Afrobeat from sweat, brass, and political defiance. His fight against corruption and cultural erasure gave Nigeria its first truly global sound, one that today’s Afrobeats stars still orbit, knowingly or not, a thread that would keep reappearing throughout the trip.

Often traveling now feels a little blasé. You see the thing, go to the thing, take the picture, check the thing off. The exploration bit rarely comes into play. Discovery and small light bulbs of inspiration everywhere, as we dived into the story behind afrobeats. Which is to also say the story of Nigeria. Over the course of a Lagos week, which is about a year in normal time - Spotify stitched together exhibitions, studio sessions, performances, fashion shows, industrial amounts :of percussion, and discussions with industry leaders shaping the genre, past, present, future.

In Lagos, everything is fast and spicy. You can apply this to almost anything from the food to the way people cut through traffic and through conversation. With a city this dense, there is little time to waste. Which is probably why, as far as my experience goes, there is no such thing as a shy Nigerian. I direct the realization to a woman dancing dramatically in a crowd at some point. She laughs mid twerk. “Shy for who? Shy for what?”. The bravado and swagger people are born with here sits on the street like humidity. The city hums with self-belief. On a pop star it becomes jet fuel. Rema. Ayra Starr. Burna Boy. Wizkid. Tems. They all have roots in this country. Rema’s ‘Calm Down’ (2.3 Billion streams on Spotify and counting) went from Benin City to the world, produced by Andre Vibez and London, then supercharged by a Selena Gomez remix that pushed it into the longest, strangest corners of global charts.

Much of that stardom has roots in one place. Mavin. Producer and executive Don Jazzy founded the Lagos based label in 2012 and built it into a finishing school and launchpad. Ayra Starr put out her second album, The Year I Turned 21, on Mavin in May 2024. Rema came through D’Prince’s Jonzing World, unveiled in 2019 within the Mavin ecosystem, and his breakout run has carried joint Jonzing World/Mavin credits with Interscope handling global push, including Calm Down. Earlier in 2024, Universal Music Group agreed to take an over $100 million majority stake in Mavin, a measure of how far the machine has scaled and where it is heading next.

It’s a slowly simmering soft power similarly seen in Korea. It doesn’t mirror the hyper-manufactured playbooks of K-pop, but there is a system. At Mavin’s studios, a cluster of old colonial villas looking out to the Atlantic, the first thing I notice is a large neon sign in the ground floor boardroom that reads The Factory. It fits. As Osamudiamen Ekunwe AKA Vaedar, Mavin’s A&R manager explains, there's a conveyor belt of raw talent being produced. Diamonds in the rough given voice training, songwriting, recording chops, styling, even cosmetic dentist appointments if needed. The second thing I notice is the walls covered in platinum selling records by the biggest afrobeats acts today. They all cut their teeth here (pun intended).

Don Jazzy has likened it to an “X-Men” model, the label approaches talent when they see potential before honing their artists’ vibe, personality, everything that would make them successful. Each artist is assigned two managers/A&Rs responsible for both brand development and day to day management.

We heard from some of the young artists benefiting from Mavin’s systems like Bayanni, Elestee and Magixx; already moving like names that matter, they have about 1.4m Instagram followers and hundreds of millions of streams between them.

They talk about long nights and early calls, but also about a supportive family and collaborative vibe that keeps them upright whilst being able to lead creatively. Maybe somewhere in the building there are the skeletons of a hundred could-have-beens who didn’t make the cut. Or maybe this is a sketch of how a modern label can run: with intent, with support, with vision, and cultural relevance - instead of the old veil of exploitation so many majors have hidden under. Everyone here is honest about the reality of the pop artist as a product, however there seems to be better product design and R & D happening before shipping.

Through the 2000s and 2010s the internet flattened taste. US and UK templates bled into MENA and Sub-Saharan Africa. Rappers laid local stories over East Coast and West Coast beats. Pop chased radio formulas built thousands of miles away. In the last few years the tide has turned. Call it a brown and black musical present. The world is leaning into sounds rooted here. Platforms like Spotify helped by dissolving geography. Somewhere in Serbia someone is playing Sawareekh’s mahraganat. In Salvador someone is deep into Omar Souleyman’s dabke. Pretty much everywhere someone has Rema on.

Amapiano for example feels like it crested in the western-trend cycle at least, the way a few micro-genres do when the algorithm gets bored. Afrobeats is still running, spawning tributaries at every tempo. Afrohouse sits in a tug of war between its Afro-centric backbone and three Berliners who are very into clouds and clout. The argument is loud because the stakes are real. The next evening I run into Vaedar backstage at the city’s biggest afrohouse club night Element House. He says Mavin is peeking into afrohouse lanes too.

Earlier in the trip we met Andre Vibez, the co producer behind ‘Calm Down’, “We need to stay true to afrobeats, and stop chasing global hits” he told us “It will end up diluting the music”. This seems to be a constant thread of tension in the current Nigerian music industry - maintaining authenticity while scaling at the rate of demand.

Two other Nigerians making an international name for themselves are rapper Vector, one of the country’s sharpest lyricists, known for weaving Yoruba philosophy and social commentary into sleek, thought-heavy hip-hop, and Spinall, a boundary-pushing DJ and producer whose blend of Afrobeats, house, and global club sounds has taken him from Lagos rooftops to Coachella.

Before meeting them we were prefaced with an Eyo display, otherwise known as the Adamu Orisha play. It’s a special type of theater Lagos usually reserves for special occasions and royal deaths and it is probably one of the hardest looking cultural-spiritual musical ceremonies in the world. A flock of hyper speed percussionists orchestrate a 30 minute performance of pure energy and ecstasy on sacred drums: the Gbedu and the Koranga. A quartet of masquerade spectres in flowing white cotton robes and veils with wide-brimmed hats, showing their house colours appear as if out of a scene from Spirited Away. They move in a slow, deliberate orbit with giant staffs striking the earth as if it was taut skin, in conversation with the percussionists. Between their passes, the women from the troupe slid in dancing with equal parts unbridled joy and disciplined synchronization. It’s a sight and sound that reaches into the cultures ancestry and will be ingrained into my brain for the foreseeable future.

Still reeling, we moved to a fireside chat with two heavyweights Spinall and Vector who discussed what it meant to be custodian for Yuruba culture in rooms that do not know what they are looking at yet. Spinall unpacked his Coachella 2024 experience where he became the first Afrobeats DJ to play a dedicated set, pulling African pop with cameos from the likes of Fireboy DML into the Sahara tent. As part of the performance he had trained Eyo dancers on stage which set off a small online skirmish, some felt staging a sacred Lagos rite outside its civic/ritual context edged into commodification, others argued it was cultural stewardship on a world stage. He explains - put traditional forms on those kinds of stages and curiosity does the rest. People go home and search. “When we sample traditional music,” Spinall added, “it gives people a reason to look deeper, to find where it comes from.

Vector followed with the philosopher-king energy he’s known for. He grew up in a Lagos Island family connected to the Eyo tradition, riffing on the line between cultural appreciation and appropriation “I don’t think Africans can appropriate culture. We live it. It’s in our bloodline”.

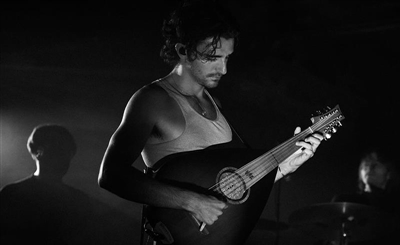

That same bloodline runs through Nigeria’s first family of music, the Kutis. We meet Fela’s grandson, genius multi-instrumentalist Mádé Kuti, who carries the lineage forward with his father Femi. Their 2021 double album Legacy+ earned a Grammy nomination. He’s calm and measured, a far cry from the frenetic, anarchic energy immortalized in the walls of the Kalakuta Museum memorializing his grandfather.

Talking about the shift from Afrobeat to today’s global Afrobeats stars, Mádé pauses to reflect, somewhat unimpressed with the braggadociousness of it all. “I think today you can chase the essence of afrobeat without it being political. It doesn’t have to be ‘the government is bad, do better.’ It’s about being introspective and being conscious. However, when there is such a stark difference, ‘I have more than you and I will flaunt it and oppress you with it’, those perspectives are anti-Africa and anti-afrobeat.”

It’s a perspective that makes more sense when you trace it back to his grandfather, Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti, the man who started it all. A musical, political and ideological vigilante and the architect of afrobeat.

I found myself staring at a newspaper clipping in Kalakuta Museum, his former home turned archive. It’s an open letter from ‘Decca Records’ about the time he commandeered the label distributing his music. Convinced he was being ripped off, he marched in with his 29 wives and the rest of his commune, occupying the premises for a couple of months to try to get the owners backed down. Not a man built for exploitation.

Fela’s music itself was radical. Long pieces built on relentless, polyrhythmic grooves, usually instrumental first, before his voice cuts in, often with horn choruses and call-and-response eruptions. Inspired by highlife, jazz, funk, traditional Yoruba rhythms and Afro-Cuban music. He sang about corruption, police brutality, and the chokehold of military rule, touring extensively throughout the 1970s and 80s, performing across Europe and in 1984 appeared at Glastonbury with his band Africa 70, later known as Egypt 80 (no we’re not going to get into the afro-centric Pyramids conversation here).

Over his lifetime, Fela was arrested more than 200 times and released upwards of 50 albums before his death in 1997. His life was chaotic, awe-inspiring, and, like many revolutionaries, seemingly only truly canonised once Western media began to fettishise his rebellion.

Half a century on, the genre has evolved from its rebellious foundation. The number of user-generated Afrobeats Spotify playlists globally has grown 135 % between 2020 and 2025. There’s been a 30% worldwide increase in Afrobeats streams in 2025, and the genre’s streams have risen 500% in MENA alone in the last five years. Getting on Spotify’s radar as an afrobeats artist then, as you can imagine, is no mean feat. I got to witness some live performances from standout emerging artists, names I’ll someday say I saw live in Nigeria before they went viral, won a Grammy, or landed a collab with Keinemusik. Kold AF, who delivered a piercingly charismatic set at a fashion show hosted by local brand Severe Nature and Spotify at Greasy Tunes, stood out as one to watch. WurlD and Spotify Radar’s Fola turned in magnetic performances, both carrying the quiet certainty of artists on the brink of global recognition, each seeming poised to hit the heights of Burna Boy or Wizkid.

The trip left me with a new playlist to flex, but also a bittersweet question. Across the Middle East and North Africa, with over 500 million people and countless hyper-local sounds, do we have one modern day artist, or even a single song, that’s truly broken through globally yet? For all the streaming success of acts like ElGrande Toto, Saint Levant, and TUL8TE, there’s still no unifying track or movement that’s travelled the way Afrobeats, Amapiano, reggaeton, or K-pop have. The talent is there. The infrastructure is building. The money’s moving in.

Perhaps that’s what’s most exciting about the region right now. It's the world’s fastest-growing music market, the reason every major label, publication, and even sovereign fund is suddenly paying attention. Because the next big thing - the first big thing - hasn’t happened yet. Perhaps there’ll be an Arab-Afro pop hit playing at the pub next time. Culture, after all, doesn’t sit still.

- Previous Article El Rass Announces Homecoming Show at KED Beirut November 15th