SceneNoise x Hiya Dialogues: Sabine Salamé

Lebanese journalist and founder of Hiya, Shirine Saad speaks to street rap artist and poet Sabine Salamé about decolonial music, the Beirut rap scene, and activism in the Arab world and its diaspora.

Introduction by Riham Issa

Interview conducted by Shirine Saad

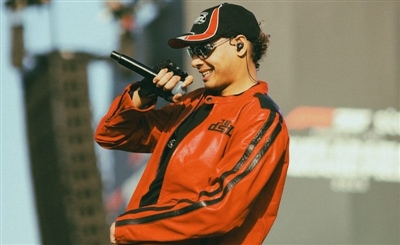

In a time where artists lmostly focus on building a certain visual identity, scavenging after digital recognition in the form of views, streams and shares, Sabine Salamé - a Lebanese street rap artist and revolutionary songwriter - favours the shadows of the underground hip-hop scene. For her, making music was never about creating short-term content to spoon-feed her audience, but rather crafting active dialogues with current political issues to build a real historical documentation of a region that’s perpetually struggling for liberation from patriarchal and colonial powers.

Despite her expansive discography in the rap scene, Sabine refuses to be labelled as ‘rapper’, nor translate her Arabic lyrics in any other language to accommodate the West. She sees her music as spoken words that happen to be influenced by her roots, the Beirut hip-hop scene, and Zajal. Growing up imbued with the classical music of Fairuz, Sabah and Asmahan, Sabine first approached making music through writing, mainly poems, as a means of self-expression. She then turned to journalism as a form of activism, but it wasn’t until she first discovered the underground hip-hop community live that she was inspired to venture into rap in an attempt to escape censorship and radically express her opinions.

Although her rap career began spontaneously, her unapologetic verses, dark, satirical and politically-charged, rendered her one of the most influential rap artists in the region who is actively persevering the gritty and raw essence of Arabic hip-hop. Her music and improvised performances, often tackling issues of immigration and political injustice, traversed borders and garnered her a loyal following across Europe.

In this new episode of SceneNoise x Hiya Dialogues, Lebanese journalist and DJ Shirine Saad speaks with Sabine about decolonizing music and how her sound evolved into what it is today. Sabine also reflects on the prime time of the Beirut rap scene, her career in journalism, and activism in the Arab world and its diaspora.

SceneNoise x Hiya Dialogues is a series conducted by Shirine Saad, highlighting radical feminist voices and influential artists from the SWANA underground scene, who are actively engaging with historical revolutionary movements to challenge the cis-heteropatriarchal and capitalist structures within the industry through their art, music, and poetry.

Shirine: Part of my personal project is to follow a train of thought that is not Western-centric, including musical language, or practising hearing in a way that is not Western-centric. Is this part of your practice as well?

Sabine: Yeah, it is just that. I write in Arabic, and a lot of people ask me why I don’t translate my songs. But a lot of them don’t translate easily because I use a lot of metaphors, and there’s a lot of play in words. Additionally, when you think in a language that is so big and wide, such as Arabic, where even the thought process and the meaning of things is different - you know, in Arabic, you have like a hundred thousand ways to say one thing, and then you have one word that means a hundred different things, and it’s funny. I can try to translate some concepts within my music, or explain what I talk about here and there, but it’s literally impossible to translate something that carries all these feelings, metaphors, and plays on words.

Shirine: Yeah, that’s so interesting, but do you feel that your audience in Europe can connect to your music in a profound way?

Sabine: That’s an interesting question… well, my Arabic-speaking audience for sure. I think people in the diaspora, especially in what I’d call the recent diaspora, who maybe grew up in their countries and had to leave in their adulthood - these people understand my music the most, because I’m mainly talking about these kinds of subjects and themes in my music.

What’s interesting, actually, is that people who don’t usually understand Arabic come to me - and this happens a lot - and tell me I didn’t understand what you were saying, but I could feel some of the energy and the feelings in this or that song. I think that’s quite beautiful as well, that people who don’t necessarily understand the words, but get some of the emotions that are there. I think that’s powerful.

Shirine: From your perspective, what are some of those feelings that this group of people connect with, and are they the same kind of feelings as they are for Arabs?

Sabine: Yeah… well, I can’t really speak for the non-Arabs because each person has their own takeaways from my music. I think a lot of what people understand and get from my performances is that there’s a specific anger that is present in a lot of my lyrics and the way I deliver the songs. I think that’s something that they can grasp without actually having to understand what I’m talking about; they can understand the feelings of sadness or nostalgia without necessarily having to understand the words I’m saying. Because when you write, it is different from when you rap or perform on stage - you’re not just writing something, and then reciting it. There’s also the effect of the sound that exists, so it’s not just words - there’s also a lot of feelings and things carried within the sound waves themselves. You know, the music that exists within the tone of your voice, like when someone’s voice breaks, you can tell they are breaking.

Shirine: How do you feel about that - that people can connect with these emotions, considering what’s going on in the world right now? There are wars and genocide in many countries in the region, fascist governments rising, refugee movements in Spain, and women’s rights movements… a lot of these topics you address directly or indirectly in your work. Do you feel that you can speak to people from different backgrounds and experiences through these themes in your music?

Sabine: First of all, I would like to address the concept of these issues of ‘right now’ because I don’t think that these issues are issues of right now, you know. I think these are issues that have always existed for the past 400 to 500 years, and they are inherently at the heart of this imperial, colonial and capitalist world that we live in. For capitalism and imperialism to function, you need to have genocide, racism, and immigration. Also, immigration is a form of resources - we are part of these resources that the West steal from what they call poor countries. And, they are poor countries because the West is stealing their resources. They are creating chaos and not allowing us to actually create our own independent governments that allow us to profit from our own resources, but also allow us to build communities.

I think this is a problem everywhere in the world, but it has one name, you know, it’s capitalist colonial imperialism. It’s the same system everywhere in the world, committing genocides, ecocides and forcing people outside of their homes and communities, and ethnically cleansing populations.

People think that colonisation stopped happening years ago, but that is not true. The only thing that changes is the branding. So, I don’t like that narrative of ‘what’s going on right now in the world’, because even the genocide of the Palestinian people didn’t start on October 7th. The Nakba happened more than 70 years ago, and there are refugee camps for Palestinians everywhere across the globe, people who were not allowed to return to their homeland even before that. And, this is something that has also been happening for over 400 years in other regions of the world - what happened in Palestine, happened in North America as well. Until today, the native population of the United States of America lives in segregated camps and reservations.

Although I like the idea that people in the US are becoming more aware of this idea of colonisation, I think they should start from the oppression that is going on in their own country first.

Shirine: How do you see the connection between your work and the history of hip-hop, how it came out in Jamaica with turntables, then migrated to New York, and the Bronx, where it lived in this sense of alienation, with people mixing records in the streets sometimes even without a mic?

Sabine: It’s not just hip-hop, but also jazz and blues and actually all of the music that exists today in the United States is music that has been appropriated from black culture and communities. Similarly, in Spain, there’s an appropriation of music that comes from South America.

This is why I don’t like to say I am a rapper, because I’m not part of that culture as well. I do create rap sometimes, it’s part of what I do, but it’s also spoken word, and there’s a lot of influence in my work from things from my own culture, which is Gazal. I have a lot of influence from it, in the way I perform. I try to bring that into my work, into something that is also from a community that I can’t really talk about, because I didn’t live it. So, I don’t even like to claim that label - I don’t do hip-hop anyway - I am not part of the hip-hop culture. I love it, but the music that I make and sing and perform to, a lot of it comes from the people of our region. Surely, they have influences from hip-hop, from a lot of different music scenes, but it also has a lot of influences from our own history and heritage.

Shrinie: Can you tell me about the music you were listening to growing up at home, and how you first started thinking about your own sound, lyrics and words, because you are a poet as well, right?

Sabine: Growing up, I never actually thought that I would rap, much less be involved in music. I liked music in general, but I think I got into it mostly because of my mom - she used to take us to jazz concerts, my brother and I, when we were kids. I used to just listen to a lot of our [classical] music, like Fairuz, Sabah, Asmahan, these kinds of stuff, but I also grew up listening to a lot of hip-hop and rap.

The aspect of writing was part of music when it came to me. I liked poetry a lot, and I started writing very early on, when I was like 11 years old. It was kind of a way for me to express myself, because I always found it so hard to express myself growing up–I’m getting better at it now. I’ve gone a long way working on myself. But it was really hard for me to admit how I feel. So, this is when I turned to writing. I needed to express these feelings somewhere, so I started writing them down into these little poems. That just stuck with me, the poetry part. Then later on, I became a journalist and started writing bigger pieces, and the poetry became something that was just for me and myself. This was up until one of my friends suggested, ‘Why don’t you start writing rap?’, because we didn’t have any female rappers in Lebanon at the time.

So, I literally started off like that, like a joke in a way, and then it suddenly developed into something. I did it once, and then sent it to that friend of mine. He sent it to everyone, and I started getting a lot of push and support from a lot of guys in the scene. Everyone was like “yeah, let’s go. We need you in here,” and so on. It was kinda like that, but I really felt that it added another layer to the poetry aspect. It is nice when I write it down, but also when I say it out loud, it gives it a different kind of power in a way.

Shirine: Tell me about the rap community in Beirut at that time. How did it influence you, and how did you feel about it?

Sabine: When I was still living in Beirut in my late teenage and early twenties, I think it was a really nice time. I got to live through a lot of events, and I got to see this rap culture kind of begin. For me, it was really important the period when we had the scene split in half; you had the guys who rapped in Arabic, and then the ones who rapped in English. And, each Wednesday, there was a group of them in Radio Beirut at the time, and I used to go there all the time, and listen to them. It was such a precious time, and there was way more space for everyone than now.

It is really nice now as well; the scene is growing in a sense where there are more rappers, and a lot of really talented guys coming out and doing really nice work. I love what they are doing. But, I feel like they have fewer places to just exist, come together, create and experiment. Back in the day, you had like two or three bars with little stages, where the guys could just hop on and just like you know, do random stuff.

To me, what was really inspirational was what Mazen [El Rass] was doing at that time. I remember when I discovered him, I was walking down the streets in Beirut and saw a poster of Adam, Darwin & El Batreek - It was the artwork for the album that he did with Homa -and, I was like, ‘Okay, let’s go and see what this is’, and I went to that concert. I remember I was completely mind-blown because I heard a lot of the guys before rapping, which was most of the time very much superficial and inspired by the West - you know, flexing or dissing each other. But when I listened to Mazen, his music was filled with all these political subjects and very rich themes, and I felt really inspired that there was a space for me to write something like that.

Mind you, I was a journalist at the time, and I had a problem with journalism, which was that I was always being extremely edited and extremely censored. There were a lot of things I wasn’t allowed to say. That really frustrated me. And then, I saw that guy [El Rass] hop on stage, basically doing a form of journalism as well, in the way that he tells you the story and the images he evokes. There was a lot there that was also informative, and a lot of events that he was documenting through his music as well.

Shirine: The scene was also important at the time, because it brought together people from different communities, and it was responding to what was going on in Palestine and Syria, etc. I was wondering how you felt about joining the scene as a woman - I guess it was about 10 years ago?

Sabine: Yeah... well, back then I wasn’t rapping. I was just someone who enjoyed rap music, and it was fine being a woman in that context, because I was like an audience member, you know. But later on, when I started rapping, I felt like it became a bit different. A lot of the guys started treating me differently as well, like I was there to compete with them or something. At the time, I realised that there are a lot of little kingdoms there, rather than one community in the Lebanese rap scene, which made me very sad.

This is something that has exhausted me for the last three years. I have been trying to change that and bring people together to create some sort of community. But then, when I do an event, if people from the scene come, I feel like they often come to size me up. I feel like this is something that has to do with the music scene in general, and how it is in Lebanon. There aren’t a lot of opportunities, so everybody feels like they have to step on the other person to make it - there’s a lot of competition.

It makes me sad because I feel like a lot of the support that I got from a lot of people in the scene was in a superficial sense, because I am a ‘woman’ or ‘talented’. You feel that people are nice to you on the surface because you have something to offer, but they don’t really try to build anything with you. Unless they see that as part of something that they are gonna profit from.

But Beirut has always been a place that’s really vicious, and now I feel like it’s a place where people kinda have to take advantage of others and be vicious themselves, in order to survive.

Shirine: I think that the problem is not only the scarcity in the local scene, but also the music scene in the region at large. A lot of people feel that to become part of the Gulf music scene, they have to have a commercial sound and use auto-tune, for example. And, for women, there’s a lot of pressure to perform femininity in so many ways, and you’re really moving away from that and keeping it very raw in your style, sound and performance. So, it’s not only because you’re a woman or in the spoken-word rap scene, I think you have so much to say. However, there are not a lot of spaces where people can understand what you say, because so many people are now accustomed to a certain commercial sound.

Sabine: Yeah, I agree that people are accustomed to a certain sound, but also, I don’t think it’s the problem of the people; it’s because the platforms that exist and the media that are in power don’t offer them anything else. I’m sure a lot of people in Lebanon would love what I do if they knew about it, but like, how are they going to know about it? Because if I don’t do the typical stuff that the industry expects of me, then I’m not going to get a push from the industry itself.

It’s actually ironic because the reason I went into music and writing was because I was very alienated as a child, only to find myself even more alienated in the music scene. This is quite sad. People would rather listen to something that is borrowed, fake and has no soul, rather than support artists who are doing something original.

One thing that I find a bit hard to accept nowadays is the idea that we are expected to be influencers as well. Yeah, I love the music that I make, and I love making music because I want to hear this kind of music, and there’s not enough female voices doing that s**t, and being hard, raw, and authentic. But, at the same time, when I do it, I feel like people are not really listening or pushing it.

At the same time, I feel that now you have to be a TikTok star to make it as a musician, but I didn’t start making music, so I stand in front of the camera and try to do this or that, and engage you with really short-term content. I feel like this is really killing music in a sense, because you have these insanely famous artists, like right now, the Arab-Americans who are even more famous than Arab artists, and you have Arab artists that are insane and putting a lot of work into their stuff, and they are giving proper content. And then you have these TikTok artists who are putting out stuff like 20-second songs, and they are even more famous because they are playing the algorithm game.

These American artists are the ones getting pushed - I call them Americans because they are Arabs who grew up in the United States, who are literally Americans, and they have no connections. Even Palestinian Americans only started talking about Palestine five minutes ago. Before that, they were just making sexy music, and now they are spearheading the whole Palestinian movement. They are now riding on this wave to make themselves famous, while artists and musicians in Palestine are eating dirt.

I feel that this aspect is very sad because it tells you a lot about the way that we consume music, and the word ‘consume’ here is very important, because this is what music has become now, it is just another thing to consume, whereas before that it had a lot of different functions that were good and others bad.

It used to be a means of resistance in a lot of places, like we said before about how hip-hop started as a means of resistance. But, now it is just something to consume, whitewashed - another aspect of capitalism and destruction. Yes, music should be something that’s for resistance, but it doesn’t mean it necessarily is, because in a lot of places it is now being used as a distraction, and a way to fetishise certain ideas. There’s just a lot of performative activism within music itself, now. Most people who now listen to music about Palestine are mainly listening to an American rapper in the diaspora talking about the Palestinian struggle, not actual Palestinian artists.

Yeah, music has the capacity to be a form of resistance, but it is also being used against us. Now, it’s more important for us to be out there, rather than being in here, creating. I feel like we’ve reached a point where making music is pointless. To me, right now, making music is not resistance. I am not resisting with my music. I’m just making music, making sounds to make myself feel better. To me, resistance right now is actually disrupting, going on the streets, trying to stop these big corporations and stop their weapons from going there. This is resistance, a direct action right there.

I’m sick of hearing that music is a means of resistance, no, shut the f*** up. Unless you’re a Palestinian musician living in Palestine, or like a Palestinian refugee, really suffering from the occupation in one way or another. Then, your music is not resistance. It is just a side quest for this resistance.

Shirine: As you said yourself, often, musicians and poets are saying things that aren’t being said anywhere else - they are speaking the truth that is not on TV, newspapers or in history books. And, your music is directly more political than a lot of the music that is coming out of the region at the moment. Certainly, in the region, there’s so much censorship in terms of the music industry, but there is still a connection, though, between the streets and the music that is coming out of the underground. I think it’s a dialogue and not isolated.

Sabine: For sure, you still have the underground artists, and those artists in the streets, there’s a form of resistance in that sense. I was talking specifically about the Western musicians who are profiting from all of that music-washing.

Sabine: For sure, you still have the underground artists, and those artists in the streets, there’s a form of resistance in that sense. I was talking specifically about the Western musicians who are profiting from all of that music-washing.

But if you look at the underground scene in the Egyptian music scene, you see entire subcultures of young rappers who are making music that’s very authentic and poetic – these guys are piss poor making that music. It's the same in Lebanon; you have these guys making music with literally zero money, and really trying to create. To me, that’s definitely part of the culture, and their music is what pushes the culture. But you are never going to see these artists on big stages or garnering hundreds of thousands of views. You are never going to see them at Coachella, or whatever.

Shirine: Elhamdullah! The space for free expression is very limited. There is this idea of constant repression. We are being repressed by the industry and the government, in the underground and in the streets. Like, in Beirut, you’re always scared that the police are going to show up, and the same in Egypt.

Sabine: Yeah, in Egypt, I know this exists because I worked with Egyptian artists, and basically, they have to censor themselves. I had this conversation a lot with Ma-Beyn; we did a project together with SHLTF, the Palestinian producer. It’s a three-track EP called ‘Nahas’.

Mariam and I had discussions about this endlessly, because she also comes from a family that’s half Palestinian, and her dad is an activist. So, Ma-Beyn is very careful about what she writes, and I’m the complete opposite of that. I went into rap, so I don’t censor myself. But I do understand her as well, because if she said one word wrong, then her entire life would be gone. She’s aware that she can’t say all that she wants to, but at the same time, she still tries to say something. That makes for a lot of creative ways that she actually writes in.

To me, it’s exhausting trying to do that, because I can’t write a text thinking of how every word can affect every person in the country. I have the privilege of writing what I want, but that doesn’t mean I’m more rebellious than her; I just have a privilege at the end of the day. I can get away with things more.

Shirine: That was really a stunning album. Can you tell me how it came together, and how the two of you met, and started collaborating with SHLTF?

Sabine: We found out that we started making music around the same time. We met online first. Someone sent her my song, ‘3lby b alb 3lby’, with the animated video. She loved that song and contacted me, saying, ‘Hey, I want to make music with you’, and sent me her latest release at that time. I liked her music and vibes. So, we started working together. That was like two years ago or so in [2022]. We actually started working on a track that we didn’t end up making at the end. At the same time, I also met SHLTF online. He lives in Lebanon, I was living here in Barcelona, and Mariam was in Cairo. So, this album was very centred on the number three: three continents, three countries, and three peoples with three identities. Lebanese, Palestinian and Egyptian. We also went with three tracks, where each title consisted of three letters.

Essentially, what happened is that SHLTF sent me a beat for 'Hawa' first, and I showed it to Ma-Beyn, and she was like, ‘Oh, this is really nice, let’s hop on it together.’ So, then I talked to him, and he said that he wants to drop the track as part of a solo EP with no lyrics on it. I was like, ‘No, let’s do the EP together.’ So, we started working on 'Hawa'; we actually wrote the whole song remotely, and then I went to Egypt. Within the course of three or four days, we wrote the two other songs and recorded and filmed the videos. It was done in a very short period of time, and I’m really proud of this project because it doesn’t sound like anything out there, it has a really nice vibe, and our different styles complement each other very well.

For me, it’s an important and precious project because we talked about us being women in the music scene, and naturally, we ended up talking about Palestine, because the Israeli attacks on Gaza had just escalated at the time. It was also a way for us to really connect these different places that are part of identities, but separated through colonialism. To us, ‘NHS’ was this kind of bridge between Egypt, Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon. That’s why I was very adamant about putting in the sentence, we say a lot in the street here, which is ‘من غزة لبيروت شعب واحد ما بيموت’, and we changed it up a bit to ‘من مصر لبيروت شعب واحد ما بيموت’.

During the process, we also talked a lot about the idea of, like, how my grandmother used to hop on a train when she was a kid and go all the way to Egypt. I feel it is really cruel for this to be taken away from us, and we never get to experience that, even though we have a lot more in common than what separates us, we share the same food, traditions and culture.

Shirine: You mentioned being interested in poetry and Zajal. This poetic tradition in the Arab world is really ancient and has so many purposes, including political or spiritual ones. You’re carrying this with you as one of those wandering poets throughout history, and also a resistance poet. Is that something you connect with as well from our history?

Sabine: In my family, specifically, there have been a couple of resistance writers and poets on my paternal grandmother's side. She is related to Saed Aael, the one whom the Ottomans hanged. He was a journalist and a poet as well. My grandfather on my mother’s side, whom I have never met, used to write poetry and Zajal. I always found it interesting to read what they’ve left behind. I find that we share a lot of things in common in the poetic way he wrote.

In the sense of being a rebellious or revolutionary author, I think I owe it to myself and my community that attempt to create something that is revolutionary in a sense. Even though, like I said, I don’t think that the music that I’m making is revolutionary. I think the work that I am doing on the streets with Palestinian organisations is more revolutionary and important. But, I think that I, being a woman, and being able to speak my mind, and offering this different way of thought, and rapping, and constructing sentences in different ways of rhyming - I am contributing something that is revolutionary in a sense. But I don’t think it’s something that people are going to appreciate now. I think years from now, people are going to realise what it is that I made. I kinda feel like I am one of those people who will be famous after they die.

Shirine: You are famous in your own way. You’ve also been so prolific, it’s incredible. Can you talk more about your latest release with SHLTF and what emotions fuelled this track?

Sabine: This track is actually different from all of my other tracks, because it is not on the emotional side. It's the closest I have to the hip-hop culture and that sense of flexing. I like it because it is more on the fun, playful side of things, and it’s also me saying that I don’t have to constantly be creating super poetic and deep stuff, I can still have fun, make people dance and move. When I play it live, it is really fun and very interactive.

The track is called ‘Te3nid’, which basically means ‘stubbornness’, and it’s like a relation to the music scene, like how it is and what we were talking about. So, it’s me saying, ‘f*** you’ - you can still be toxic and I’m gonna still do my s*** and make amazing things, and drop things that not of you can't imagine and people are still going to listen to it’. It’s just me flexing that aspect and being relevant as opposed to in a non-relevant way.

Shirine: It’s so good. Is there something else or a message you want to share?

Sabine: I collaborated recently with Liliane Chlela, who is absolutely brilliant, and it is something that I am so proud of. I really appreciate the few women that we have in the music scene in Lebanon who are really pushing the envelope and creating new sounds. I feel like this is also important for me to work on now, as well- this creation of the sounds that make up our community as Lebanese female artists.

- Previous Article Hassan Yasser Drops Boom Bap-Trap Shaabi EP 'Ma3rfsh Bansa Wala La2a'

- Next Article Select 347: Looswing