Ahmed Fouad Negm and Sheikh Imam’s ‘Ana Atoub An Hobak’

The dynamic duo shook the region with their pained odes of rebellion and of hope.

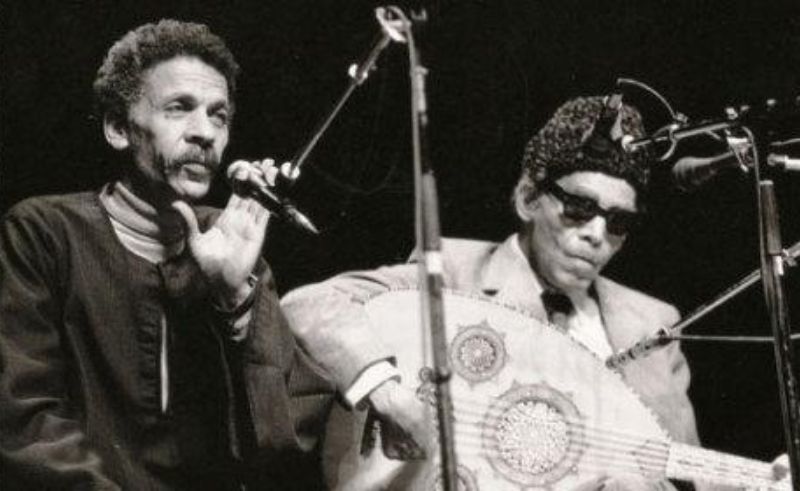

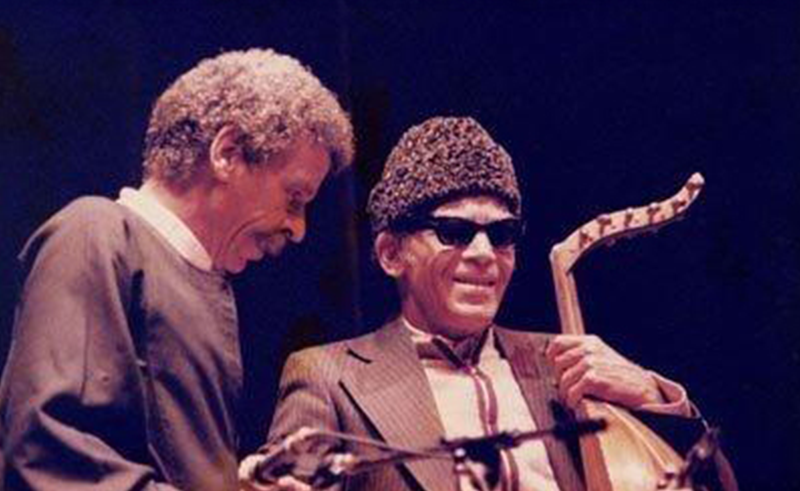

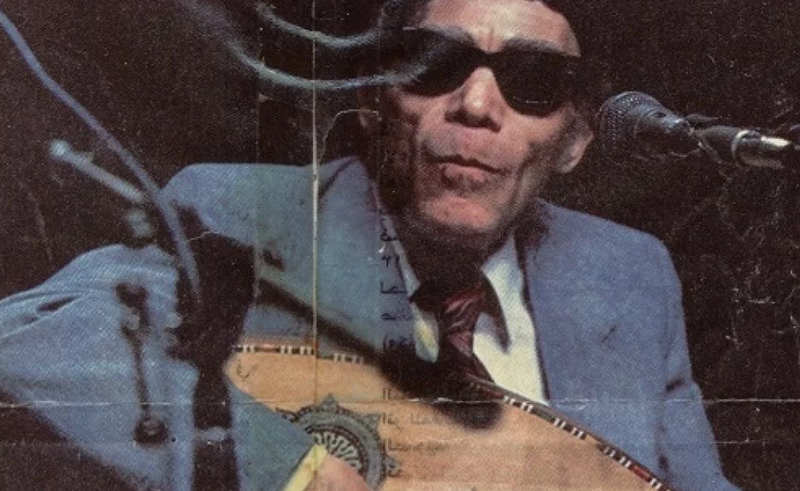

On a fateful day in 1962, a gangly, gallabeya-clad dissident poet met a blind, sunglassed balladeer and oudist at a salon hosted by famed society host Saad El Mougy. The poet had just been released from a three-year stint in prison and had emerged as a respected figure, praising the virtues and values of Egypt’s working classes. The oudist had been a prominent feature of Cairene oud salons for a while, his Quranically trained voice singing ballads against injustice. At their first meeting, the two dissidents bonded over their shared rejection of contemporary Nasserist leftism and the liberalism that had dominated Egypt under the monarchy.

To them, the way forward for a truly egalitarian Egyptian cultural and musical tradition lay in using the language of the common man over intellectual diatribes and expressing the authentic lived realities of their countrymen—unable to afford the staple foul meal, their sons enmeshed in countless lost wars, and their voices silenced by an oppressive regime. Quickly forming a strong bond that would persist for the next thirty years, the poet Ahmed Fouad Negm moved into the simple lodgings of his companion, the blind oudist Sheikh Imam. Shortly after, the duo released their first collaborative composition, “Ana Atoub An Hobak.” The song quickly became recognized in local lore as a profession of the love between the two men. As their lives became more complex and their music increasingly anti-establishment, they often found themselves apart and languishing in separate prison cells for years. The song, an expression of longing for the beloved friend, came to symbolize the profound anguish of separation from a close companion.

In the immense and profound oeuvre of the legendary duo Sheikh Imam and Ahmed Fouad Negm, their ballad “Ana Atoub An Hobak” stands out. Not an overtly political song, it is a revolutionary praise of the love that can exist between close male friends in a world that expects them to be harsh and unfeeling. Personally, the song holds much weight and very early on became a personal anthem between my brother and me. The song speaks of longing for the intimacy of the beloved after years of separation and of the strong knowledge that neither separation nor disagreements can sway the enduring strength of a brotherhood. The refrain goes, “En kan amal el 3osha2 el 2orb/Ana amaly fe hobak/ Howa el hob,” suggesting that while romantic lovers long for closeness, the brotherhood between best friends can exist simply in the fact that the love between them endures—physical closeness plays no part in the lessening or strengthening of this love.

It is perhaps one of the most classic ballads in praise of what we now colloquially call a “bromance.” Often abroad, I would listen to this song and think of my brother in Cairo, reminiscing about our growth together in the streets of a harsh city where we created our peaceful kingdom, and longing for our reunion. I knew that however much time had passed, the love shared between us would not have lessened. I would remember the ahawi, alleyways, bars, and scenes where we would play and learn the safety that comes with companionship and the softness that can exist between men in a society that seeks to create ruggedness and aggression. The song, though not political, is still a rebellion against social norms, an embrace of gentleness, and a shattering of stereotypes. My personal connection to this song is not unique, and no doubt it brings many Arab men displaced throughout the world—for political, economic, or social reasons—back to the Cairo, Damascus, Tunis, or Tripoli of their youths. It brings them back to the simplicity of walking arm-in-arm with their brothers through streets they call their own, in neighborhoods where their names are known together and not independently, to old people from the neighborhood who ask about the whereabouts of the other half when they are not with you.

My personal connection to this song is not unique, and no doubt it brings many Arab men displaced throughout the world—for political, economic, or social reasons—back to the Cairo, Damascus, Tunis, or Tripoli of their youths. It brings them back to the simplicity of walking arm-in-arm with their brothers through streets they call their own, in neighborhoods where their names are known together and not independently, to old people from the neighborhood who ask about the whereabouts of the other half when they are not with you.

In the Western imagination, Arab masculinity has, since the early days of colonialism, been viewed as savage, unenlightened, backward, and unfeeling. Oppressive toward their women and aggressive with their fellow men, the Arab man was reduced to a caricature of cruelty and provincialism. Any student of Arab masculinity, or indeed any Arab male or female, can attest to the falsity of such a perception. There exists a patriarchal essence in our societies, but to view the Arab male as solely patriarchal and unfeeling is to reduce us to a version created by those who sought to conquer, destroy, and change the beautiful ways we express tenderness.

To the softness of our men who put jasmine blossoms behind their ears in the springtime, to the image of best friends kissing and hugging and roaming the streets with arms intertwined. Perhaps the expression of tenderness often shown between Arab males has been best described in the region’s literature and music. Far beyond the ravages of our war-torn region and the socio-economic realities that have reduced numbers of our men to begging, emigrating, or falling into addiction and mental illness, there still exists in our society an immense love freely shown between males. Childhood best friends who have remained beside us into our adulthoods, old men playing tawla in our local ahawi who have known each other their whole lives, supporting each other through wars, economic depressions, and political upheavals. Perhaps no duo in our cultural scene has more representatively shown this softness, this tenderness, between male best friends than the legendary oud player Sheikh Imam and the dissident poet who was always by his side, Ahmed Fouad Negm. Particularly, their collaboration produced their most popular love song, “Ana Atoub An Hobak”—a ballad held in local lore to have been written by Negm to his lifelong companion, comrade, and strength, Sheikh Imam.

Perhaps no duo in our cultural scene has more representatively shown this softness, this tenderness, between male best friends than the legendary oud player Sheikh Imam and the dissident poet who was always by his side, Ahmed Fouad Negm. Particularly, their collaboration produced their most popular love song, “Ana Atoub An Hobak”—a ballad held in local lore to have been written by Negm to his lifelong companion, comrade, and strength, Sheikh Imam.

After one of my long stints abroad, I returned to Cairo and immediately met my brother at our local ahwa at 3 AM. The soft incense of jasmine and bougainvillea wafted in the gentle breeze of spring. After an embrace and holding back tears and lumps in our throats, we sat down, smoked a shisha, and simply looked at one another, recounting for hours all the stories that had happened in our lives during the absence of the other. Imam croons, “Tewselny seneen/ Tehgorny seneen/ Matghayarnesh ana hoby kbeer.” After our early morning catch-up, we decided to retreat for a small beer to one of our favorite Downtown bars. A den of old men who have known each other for decades, the patrons and owners of this particular bar had seen us grow from boys to men—it is one of our special spots. Upon entering, our names are called in tandem with delight by the waiters, signaling the others to organize chairs for us.

We sip on a Stella, still recounting these stories that occurred in the other's absence. Suddenly, another duo walks in and sits close by. In their possession, a tabla, an oud, and a voice like honey. The duo starts singing “Ana Atoub An Hobak,” and the boisterous heckling of the bar dies down to quiet. As the rhythm of this ode to brotherhood takes heat, hands start tapping on tabletops, and agèd refrains break out from emotional voices. The whole bar joins in, gripping the necks of their mates beside them, quavering in harmony and unison, “En kan amal el 3osha2 el 2orb/ Ana amaly fe hobak/ Howa el hob.” I look at my brother and we smile. Life imitates art once again, and the duo that once shook the region to tears and rage lives on in the duos that exist today.

- Previous Article Moroccan Artist Tawsen Releases Rai/R&B Album ‘Ne3ne3 Radio’

- Next Article XP News: MENA Artists' Iconic Performances on ColorsXStudio

Trending This Month

-

Jan 29, 2026