When Khartoum Birthed Arab Jazz: A Musical History

Khartoum was once at the height of African and Arab jazz culture, where a hedonistic group of musicians birthed Arab jazz.

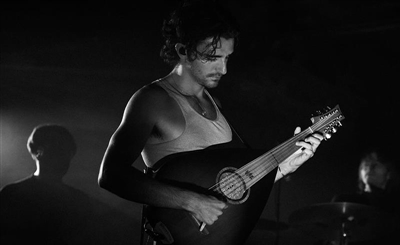

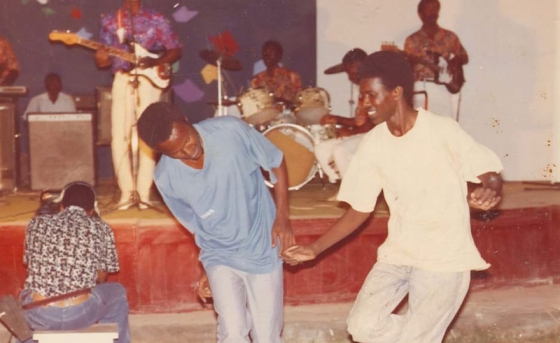

In the not so distant past, Sudan’s Khartoum was at the height of African and Arab jazz culture, an irresistible city of chic, glittering mini-skirts and coiffed beehives, and men in the swankiest suits and shining brogues dancing the tango and samba to the beats of the city’s singing kings. A hedonistic, expressive and joyful community of singers, guitarists, and percussionists of all sorts banded together at the city’s swankiest hotels and cafes to create a sound that would be at the forefront of Arab jazz for decades. Here, the names now forever-associated with that distinct, upbeat bop of Sudanese jazz accompanied by poetic and soulful vocal renditions was birthed - Sharhabil Ahmed and Mohamed El Amin chief amongst them.

The history of Sudan’s jazz culture dates back to as early as the 1920s, when a type of music known as haqeeba or ‘briefcase’ became a common sound on Mohamed Ahmed Salih’s radio show on Radio Omdurman. Rich in poetic meaning (as Sudanese lyrics in general often are), the voices of the lead singer and choir would be accompanied by the percussion of tambourines and drums. This early nascent form of jazz would morph into the sound of the more global sounding jazz in the 1940s, when haqeeba would fuse with the emerging Western-jazz movements in Egypt and the rest of the Arab world, and incorporate Western instruments such as the guitar and trumpet.

Perhaps inspired by the rise of Black music in America (which would go on to become some of the most popular music in Europe and the US during the WWII years), Sudanese jazz specifically incorporated elements of blues, rock ‘n roll and East African harmonies. As with Ethiopian jazz, which developed at a similar time, a deep melancholic melody was often merged with upbeat and falsetto vocals to create an experience of the erstwhile Western jazz which was particularly African, and in Sudan, sung in the Sudanese dialect of the Arabic language.

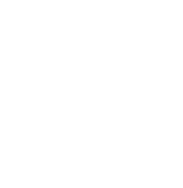

As the genre grew in traction amongst the Sudanese audience, numerous jazz bands began springing up across the capital, with the two most popular venues being the concert halls of the St. James Music Hall and the Gordon Music Hall, where swanky Khartoum hipsters and the more classically influenced dancers would merge to enjoy nights of soulful ballads and upbeat tunes. Here, bands such as the Bluestars led by William Andrea, The Scorpions featuring performers like Al-Tayeb Rabeh and Amer Nasser, and the Dayum Jazz Band would all take on their distinct characters.

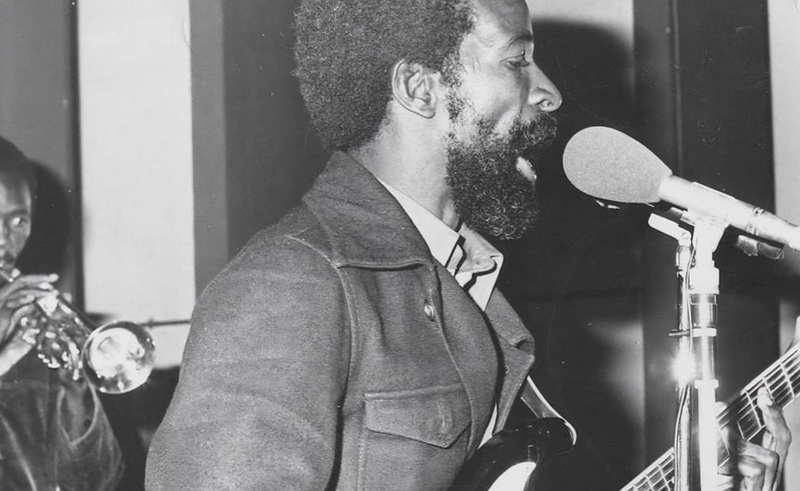

Once Sudan gained independence from the UK and Egypt in 1956, the genre flourished, with the period between the 1960s and 1983 popularly referred to as the ‘Golden Age of Sudanese Jazz’. This period saw the emergence of the still-adored artist Sharhabil Ahmed, the creator of such venerated songs as ‘Hamset Shouq’ and ‘Argos Farfish’, who has recently brought back to the popular culture through the reissuing of his records as part of a collaboration with Habibi Funk. Ahmed was born in the city of Omdurman in 1935, in its bohemian and artistic Abbaseya district - home to many of the country’s most respected artists. He subsequently became entrenched in the Khartoum jazz scene and renowned for his music all throughout Africa and the Arab world, transporting Sudanese jazz to surrounding countries and cementing his place in global musical history.

At the accession of Gaafar Nimeiry to the presidency in 1969, jazz culture took on a more flagrantly political tone. Nimeiry crafted himself as an Arab socialist a la Abdel Nasser and Gaddafi. His repressive policies towards the South Sudanese, and his abhorrence of ‘Westerness’ in general, was rebelled against both in the cosmopolitan nature of jazz itself as well as in the creation of numerous songs criticising government policy such as Kamal Keila’s songs ‘Muslims and Christians’ and ‘Agricultural Revolution’, encouraging a reconciliatory policy between Sudan’s South and North.

In the 1980s, the formerly secular Nimeiry started incorporating right wing religious Islamist policy into the nation’s laws, leading to a dramatic closing of Khartoum’s nightlife venues and flourishing music scene. Most of the legends of Sudanese music fled into exile in Egypt and neighbouring countries, and the country’s famed jazz scene was quelled into virtual nothingness.

As Sudan goes through a ravaging civil war, and mental imagery of the country is reduced to that of suffering and bloodshed, it becomes ever more acute to remember the depths of this country’s cultural and musical histories. Once the home and birthplace of Arab jazz, the melodies that made Khartoum swing in the 1960s has reemerged in modern popular culture as a joyful expression of an Arab world of mini-skirts, dancing couples and a hedonism which took the region’s youth beyond the social and political realities of the time, to a space of liberty and freedom.