Reimagining Nostalgia Through Morocco’s Nanofunk

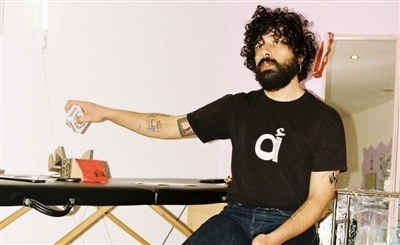

Morocco’s Jalal Yassine integrates electronic sounds with the auditory elements of classic gaming consoles.

Jalal Yassine, a Moroccan sound artist, DJ and producer, has found a way to masterfully blend electronic music with retro gaming consoles through his project, Nanofunk.

His journey began with a fascination for analog and vintage technology, particularly vintage synthesizers and drum machines. This obsession with nostalgia led him to collect several classic consoles such as those made by Atari and Sega, all of which he uses to craft a unique concept that marries his love for 8-bit retro gaming with electronic music production. He does this by using several Game Boys and Nintendo consoles, connecting them to a mixer and sampling them to incorporate sounds during live performances.

Alongside his music, Jalal also delves into photography, having launched a project called ‘Casablanca in Vexels’, a series of images captured using the Game Boy camera. As the first Moroccan, African, and possibly Middle Eastern artist to professionally work with this vintage device for photography, his series reimagines Moroccan streets and culture through a retro, pixelated lens.

His work has been showcased at a multitude of prestigious events, art zones, and festivals, streaming his music on local and international electronic music platforms and radio stations, including in places like Italy and the UK.

SceneNoise caught up with him for a quick one on one to find out more about the rising talent. The first 15 minutes of our chat were spent discussing Morocco’s vibrant art scene against the sounds of what could only be described as a blender powered by shaky wifi and the roar of traffic in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where Jalal was speaking from. We couldn't make heads or tails of what the other was saying, but there was a beautiful sense of urgency about it.

So, where are you exactly?

Sorry, the cars are super loud here. I don’t know if you can hear me. It might be my Airpods too. Let me see if I can remove them.

(The sound of a large truck horn blasts by Jalal, followed by a sudden, deafening silence.)

Are you okay?

Yes, I feel like no airpods are much better.

Next time, we can call from my Game Boy.

Yes! I was hoping that would be the case this time.

Not this time, no. We have a deal for next time though.

Nanofunk is an interesting term. Is it just your stage name, or would you say it's also the genre?

Nanofunk is both. It’s the setup I use, which is very unique to me. You could say it’s my brand and my personal touch. The way I experiment with sounds is a huge part of it, and I try to push boundaries and create something that’s never been done before. But it’s also a genre in the sense that I’m constantly trying to create new and unique sounds through it. It’s a creative process, a genre that allows me to explore new ways of making music, so I’d say it’s both a personal project and a genre I’m developing.

What do you think is the relationship between nostalgia and your work?

Everything actually started a long time ago, from when I was a child. I couldn’t afford a Game Boy back then, and it was a big challenge waiting for my parents to get one. Now that I’m older, things from the past come back to me. I started collecting consoles, and that became part of my creative process.

For me, having a Game Boy in my setup is important - it’s not only for nostalgia, but also for the future. When people see the Game Boy during a live show, it triggers that childhood memory, that nostalgic feeling. But then, as the audience listens to the sounds and the music, they start to experience this mix of the past and modern music. It’s about bringing those memories into the present and creating something out of it.

Do you remember the first piece of music you ever composed?

Yeah, the first thing I did was use a sampler with my phone and the Game Boy. I’d sample sounds from old Moroccan videos I found on Instagram, mix them with music, and see what came out. It was experimental, like Tetris. Just a lot of trial and error.

Can you tell me a little bit more about the photography you do with the Game Boy camera?

Yeah, absolutely. So, I’m actually the first Moroccan and African artist, or maybe even the first Middle Eastern artist, who created a series of images using the old Game Boy camera. My series is called ‘Casablanca in Vexels’, or ‘Moroccan Vexels’. I’ve exhibited it in Morocco across many art spaces.

It’s been a crazy, unique experience both for me and the audience. Through this series, I’ve essentially given Morocco a 2-bit, old gaming aesthetic - a “vexelized” look. I’ve had collective and solo exhibitions, and the feedback has been incredible.

This project also opened the door to creating visual projections for my live performances as an artist. By using the Game Boy camera visuals, I evoke that nostalgic, back-to-the-past feeling. People connect with it because it blends the familiar warmth of the past with something fresh and unexpected.

It took some digging to find that because it wasn’t on your profile. I’m curious to know more, though - you seem to be tackling nostalgia in so many mediums.

Yeah, I don’t post a lot about it on my personal account, but the project is tagged under Moroccan Vexels. The idea behind it is about finding beauty in limitation. Today, everyone is chasing high-tech tools, high-resolution cameras, and the latest innovations. But what about imperfections?

There’s something pure and beautiful in the constraints of old technology - perfection in imperfection. That’s the essence of the project: pushing those limits to create something meaningful and unique.

I totally agree with you - imperfections have a way of keeping art grounded, especially in a time when AI and polished aesthetics are becoming more dominant every day. So, when you say “finding beauty in limitation,” does this apply to your music as well?

I mean, that’s the beauty of this concept I’m working with. I’ve noticed that everyone interprets the images and sounds differently, which is so fascinating. Sometimes, I’ll ask people, ‘What do you see here?’ and the responses are always completely unique. That’s the thing about the low-fi, blurry quality I embrace—much like my music, it creates space for imagination, it allows people to project their own ideas and experiences onto the work. It’s not about me telling them what it is; it’s about them discovering what it means to them

Speaking of your music, how did you start combining Game Boy visuals with your performances?

At first, I used a sampler and my phone alongside the Game Boy camera. I’d sample old Moroccan songs and sounds, mix them, and create experimental tracks. It was like playing Tetris - piecing together elements until they clicked.

What did you find the most difficult part of performing live with that kind of setup?

The technical limitations are definitely the biggest challenge. When you’re performing live with these old consoles, you don’t have the luxury of syncing options, so everything relies on your ears, rhythm, and intuition. You have to stay incredibly focused, and it can be really tough to keep everything in sync, but when it works, the payoff is something unique and rewarding. It’s a delicate balance between precision and improvisation.

Do you hope to see other artists explore Nanofunk as a genre, or do you feel a sense of ownership over this particular vision?

Absolutely. I want to see people connect with the past and experiment with older technologies. You don’t need the latest, high-end tools to create something impactful. Sometimes, the smallest, simplest setups can lead to the most meaningful expressions.

I don’t want to take up too much of your time, but this has been a really great conversation. I appreciate you sharing so much, and I wish you all the best with what’s ahead.

Hey, no, thank you. I’ve really enjoyed this, too. Hopefully next time we do an interview, it’ll be in Egypt, and I’ll be performing there.

You can find Jalal’s music on Instagram under @nano.funkmusic and on Soundcloud under ‘nanofunk’