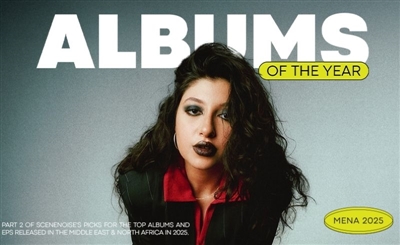

On Sahar, a Peek Inside Tamino’s Pandemic Quarters

Scene Noise caught up with the Egyptian/Belgian artist on tour in New York to discuss his latest record, his new love affair with the oud, and returning to the stage.

Tamino ended his U.S. tour on a rainy Brooklyn night in mid-October, the weather and season and music together foretelling the cold months ahead. When the lights came up, the artist was alone onstage, fog curling around his lanky figure, the angled beams sharpening the planes of his face. He opened with ‘A Drop of Blood’, a somber ballad that uses the oud as a main accompanying instrument. There is a tendency in Tamino’s music for songs to build in intensity, from a low pitch to a soaring falsetto, a gentle strum to a full acoustic sound. His opening number leaned into that form, the oud growing louder, the reverb more insistent, his voice slowly filling up the room’s negative space.

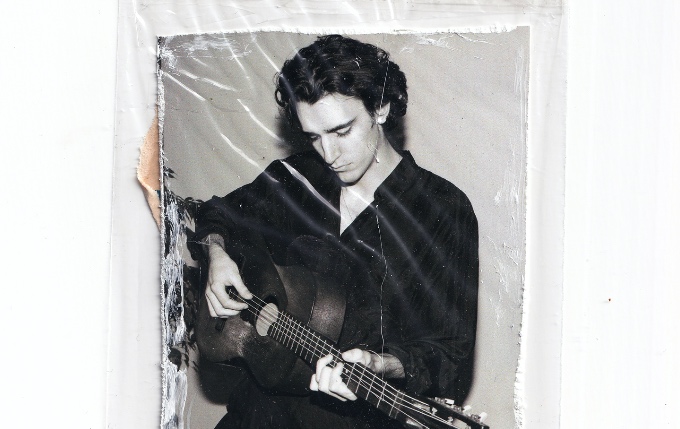

Photo Credit: Gabriel De Rossi

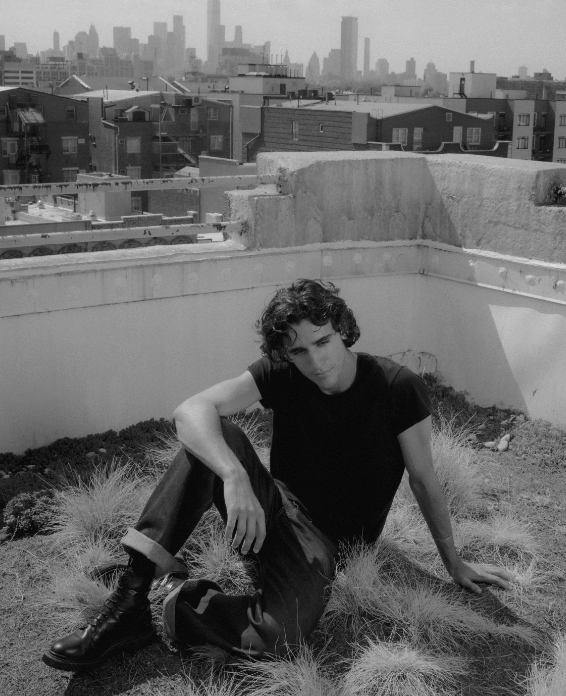

Photo Credit: Gabriel De Rossi

The tour marked the release of the Belgian-Egyptian singer-songwriter’s second album Sahar, an Arabic word that means ‘just before dawn’. Compared to his debut record, this one is more understated and roomy, qualities that he attributes to the period in which it was written.

“It's very true to what my life looked like sonically. I wasn't performing at that time,” Tamino told SceneNoise. “On the first record I think you really hear the influence of playing live. You know, being on stage and being in front of big crowds for the first time in my life.”

After winning a Belgian radio competition five years ago at the age of 21, Tamino-Amir Moharam Fouad, known mononymously as Tamino, catapulted to major stages across Europe, attracting the admiration of artists such as Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood and Lana Del Ray. His debut album Amir came together during this time, its Arabic orchestral arrangements, indie rock riffs, and wide vocal range producing a unique sound that won him fans from Paris to Istanbul.

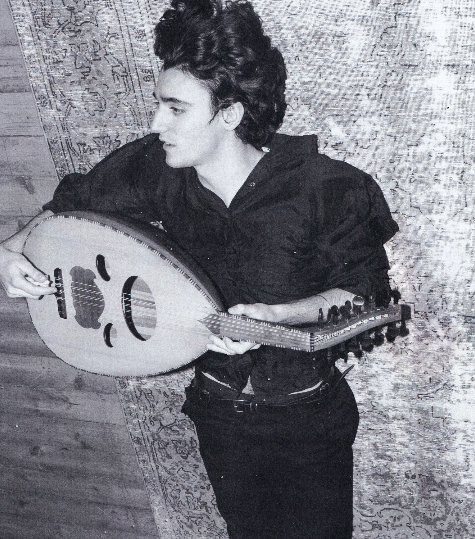

Photo Credit: Jeton Bakalli

But while on the road promoting the album, the pandemic broke out, cutting short his tour. The artist suddenly found himself back in his hometown of Antwerp under lockdown. He moved into a new flat and, with the time to finally process the past several years, started writing music. The result of that introspective period is the ten tracks that make up Sahar, an album that is at once subdued and stirring. On it, we are let into Tamino’s pandemic quarters where he spent time experimenting with blends of different acoustic instruments, pedals and synthesizers.

While Sahar is decidedly less cinematic than Amir, it is not without its surprising moments. On ‘Fascination’, a simple acoustic riff is interrupted by a shock of rhythm as the band comes in, and major seventh chords add a mysterious depth to the melody. The album takes another unpredictable turn with ‘Cinnamon’, a loose and summery track inspired by Tamino’s college years in Amsterdam where he spent time smoking hash in his room rather than realizing the “big dreams” he’d had for his life there. And then there’s ‘A Drop of Blood’, which he says is the only track on the album that he pictured before writing. He knew that he wanted to write a song on the oud in the same tradition as his grandfather, the legendary Egyptian musician and actor Muharram El-Fouad. He began learning to play the instrument with the help of a Syrian musician who had found refuge in Belgium, and gradually gained proficiency.

Photo Credit: Jan Philipzen

Writing songs on the oud is a vastly different experience to what he is used to, Tamino said. On guitar, a musician selects a key and works within its harmonic world. The oud, on the other hand, asks players to construct melodies without consideration for scales or chord formations. He described the process as “liberating.”

“They call it the instrument of the soul and I kind of get it now. It sort of lures you to just play very naturally whatever comes up,” he said. “It made me write songs that I would have never written otherwise.”

If the years of writing and experimentation in his home studio were freeing, a return to the stage threatens to provoke the opposite sensation. Tamino enjoys touring, describing the chief job of a musician as bringing people together to experience a moment. Ideally, he mused, they are individuals from different walks of life or political perspectives who ordinarily would not share space. But performance can also be constricting, the prospect of a show being uploaded to the internet mere minutes after its close, discouraging live experimentation. And touring is a varied experience, a blur of cities and sound checks, some moments of inspiration and others of weariness.

“It's an illusion to think that playing the same songs night after night can bring the same amount of pleasure or surprise,” Tamino said. “Some shows are just great and you don't really know why per se, you just enjoy them more, and some aren't.” On that October night at the end of his U.S. tour, Tamino appeared gratified and at ease. He played a few opening songs before addressing the crowd.

“New York… wow.” He pronounced the name of the city as if it were a prize. “We’ve had a long tour. This is the last night, this is the last night of our tour,” he continued to thundering applause, his voice betraying his own surprise. “It’s already legendary.”

He had selected a variety of songs from his first two records for the show. From Amir, he played ‘Tummy’, a song whose listless opening verses give way to an airy and yearning chorus that everyone sang in unison, and ‘Indigo Night’, a narrative track that bears the mark of Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood in the studio. And from Sahar, among other tracks, ‘My Dearest Friend and Enemy’, a heartrending admission of young love’s propensity to hold people back from where they ought to be going.

Halfway through the show, Tamino paused to ask the crowd if there were any Chris Cornell fans amongst them. A few enthusiastic shouts, along with an “RIP!” from the back of the room made it clear that the vast majority were unfamiliar with the late singer-songwriter, best known for his work with the rock bands Soundgarden and Audioslave. Tamino then launched into ‘Seasons’, a brooding track from Cornell’s 1990s solo work. His decision to include it in the set offered a glimpse of what he’s listened to while writing Sahar and also spoke to his versatility as an artist.

While many would put Tamino squarely in the camp of indie or alternative rock, the full body of his word includes myriad influences from American folk to classic Arabic maqam and hard rock. This is what makes him exciting as an artist; he’s not afraid to let every kind of sound bleed into his music.

Tamino closed with ‘Habibi’, the smoldering crowd favorite that reveals the raw power of his voice, which sweeps effortlessly from a deep register to an operatic falsetto, even more impressive live than it is in the studio.

When he finished playing he stood grinning at the shouts and thundering applause, and then slowly made his way up the ramp to the door leading backstage. He stole one last look behind him and raised his hand in farewell as the lights cut out.

- Previous Article test list 1 noise 2024-03-13

- Next Article Need For Speed Unbound’ OST to Feature Several Arab Rappers

Trending This Month

-

Dec 15, 2025

-

Dec 24, 2025