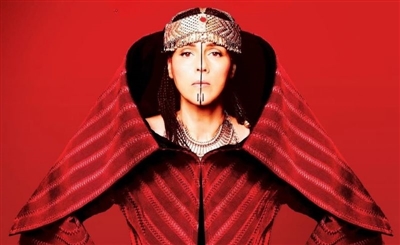

Meet Khaled Rohaim: the Egyptian Producing for Ariana Grande & Rihanna

In this exclusive interview with Grammy-nominated and multi-Platinum producer Khaled Rohaim, we learn all about how he stays humble - and how that led him to work alongside Doja Cat, Rihanna and Wegz.

I learned of the name ‘Khaled Rohaim’ a few months ago. As is common when someone is a global success, whispers began of his return to Egypt, his homeland. “He’s produced for Rihanna,” and “He’s worked with Wegz”, were amongst a few of the claims that perked my ears.

As an Afro-Arab third culture person with a near obsession with seeing ‘our people’ cross over to the mainstream, I was surprised at my unfamiliarity with the name, and did my research. His jaw-dropping resume wasn’t hard to find - multi-Platinum, Grammy-nominated producer/composer, credited alongside the likes of Ariana Grande, Zayn Malik, Meghan Trainor, Travis Scott, The Kid LAROI, and more.

Questions began swirling. I had the privilege of meeting and becoming acquainted with his manager of affairs in the MENA region Menna Dief and asked if Rohaim would be down for an interview. Eventually, I was (virtually) face-to-face with one of the music industry’s most prized producers. The conversation that ensued was nothing short of spectacular.

Speaking to me from Sydney, Australia, where Rohaim was born and raised, Rohaim began detailing his beginnings in a thick Australian accent. “My mother moved here when she was about nine or ten years old. My Dad was touring with Omar Khorshid, the guitar player as his keyboard player and music director for the band. When Omar Khorshid passed, Allah yer7amo, my dad married my mother and started a new life in Australia.”

Omar Khorshid, for those who may not know, is what Rohaim once described in an interview with The Sydney Herald earlier this year as “The Santana of Arabia” -- a globally renowned Egyptian guitarist and composer. For Rohaim’s father to be his keyboardist and musical director tells us that music is in Rohaim’s blood. Later in the conversation I learn that his ancestors are legends in music as well, playing for Egypt’s biggest artists, such as Abdel Halim. “This is what I saw growing up,” Rohaim tells me about carrying on the tradition of providing through music. “I had so many different production names over the years…so I was like, I’m just going to use my full name. Because that’s our family’s legacy.”

It was apparent that music was in Rohaim’s destiny since he was as young as nine, when he started producing, knowing for certain this was his path. An inspiring start -- marred, however, by the unfortunate passing of his mother. “After my mother passed, Allah yerhama, my father felt like he had nothing. He sold everything and we packed up and moved back to Egypt.”

It was a short return, as two years later they moved back to Sydney -- but the visit was long enough to keep Egypt in Rohaim’s heart. “I love Egypt. If I could live there I would.” There was longing in his voice -- intriguing to hear from someone planning a move to LA, the city of glitz and glamour, to be closer to his work as a hit producer in an enviable industry. This, however, is where Rohaim’s core persona as a humble family man is revealed.

“Family is important and I have a large family in Egypt who I love very much. And there’s something about being in the Middle East as opposed to the West, especially as a Muslim. It’s tough growing up Muslim in the West.”

Rohaim, who considers himself a practicising Muslim, found intolerance towards his faith in the home he grew up in. This, as well as an occasionally insatiable living situation, drove Rohaim to want to leave his hometown in Sydney. “There were times when we were sleeping on the floor for ten years at a time. I also married really young, at 19, had a kid by 20… I was working four jobs at a time and doing music at night. Music felt like a way out for me, for sure.”

How does one in those circumstances eventually come to produce for some of the biggest artists in the world? They say luck favours the prepared, and in Rohaim’s case, his stroke of luck, his blessing, came in the most serendipitous form. “I was working as a pest exterminator. I went to spray this dude’s house one day, and he had Australian APRA music awards up,” Rohaim shares. “He turned out to be a producer and songwriter. I just told him, ‘I make beats bro,’ and he said ‘Send some,’ so I did, and ended up getting my first placement on a major label here.”

With a $4,000 cheque in hand as a result of perhaps a few hours of work, made easy by years of experience, Rohaim saw a tangible opportunity to make a living from his craft. After partnering with Filipino songwriter, producer, and artist Israel Cruz, Rohaim found himself at a production gig in New York. “I was proving myself. I didn’t leave the studio, I slept there for like a week straight, and I just made as much music as I could possibly make. By the end of that week, I got offered a production deal for a company called Orange Factory music, and they were in-house production for Cash Money Records.”

Hip-hop heads will of course recognize this label as the legendary platform that gave rise to stars like Drake and Nicki Minaj, headed by Lil Wayne. Though Rohaim’s time at Cash Money was before these superstars were recruited, it was still the biggest opportunity of Rohaim’s life so far, and one that secured him more money at one time than he had ever seen in his life.

Most young men would go mad at such an experience. Many artists are known to blow their label advances on cars, jewellery -- superficial things. But they say that money doesn’t change you, it just reveals who you really are. And Rohaim’s initial reaction upon his success revealed the family man he is at his core. “I thought to myself, I can get my wife and two kids out.”

Rohaim speaks of his life at that point as though it were a prison, and to him it was. But some reprise was found when he used his Cash Money advance to move his family into a bigger house and set up his own studio at home. After years of work, travelling back and forth, and working with peers who are now top executives and artists in the industry, Rohaim had created a solid network for himself. And of course, his work ethic always spoke for him as much as his talent did. “I was hustling… sleeping on floors in Harlem, getting up and walking twenty blocks to get to the studio. I did the hard work from the ground up,” Rohaim tells me.

It’s impossible to not be moved by Rohaim’s story -- and challenging to not be floored by the things he experienced and sacrificed purely for the passion and potential he saw in this career. “My first trip to LA was self-funded. I borrowed a thousand dollars from a friend and had another thousand with me, and the first studio session I found myself in was with Kendrick Lamar and Jay Rock in a backyard studio in Watts, California.”

Rohaim has unseen footage of Lamar (who at the time was known as K.Dot), Jay Rock, and MixedByAli. I joked that he could sell that footage to TDE for hefty money. “I’d gift it to them if I could find the footage,” Rohaim responds -- another testament to his character. From the conversation it’s clear that Rohaim is truly as decent as they come. I wonder at this point how he has survived such a cutthroat industry, one notorious for its dirty business, backstabbing, and shady practices. There’s a reason why people say those who found success in the music industry had to ‘sell their souls’ to get there -- but Rohaim’s appears intact. I probe a little deeper, curious if there’s ever been a human glitch in the armour.

“Coming up with your peers, have there ever been any elements of competition? Any hurdles along the way?” I ask. Rohaim cuts me off here.

“So many, Nadine,” and his voice carries the burden of those experiences. “The music business is an emotional rollercoaster. There is definitely an element of competition. The older you grow, and the wiser you get, the better it becomes… I switched my mentality a really, really long time ago… At some point I just decided, I just want to collaborate with all my friends doing music, and until now we do, and we kill it. Across myself and my circles, we produce everything that comes out.”

Rohaim’s catalogue can attest to this, as he’s credited as a contributing producer and songwriter on some of our generation’s most coveted hit songs. I ask him how the process of collaboration works with producers. “This person will be in this room and say ‘send me this idea’, ‘I’m working with this artist today, send me ideas,’ -- we keep it moving like that.”

This was apparently the process behind the Doja Cat collaboration, where he’s credited on ‘Love to Dream’, a song off her latest Grammy winning album ‘Woman’. “She was on the final day of handing in her album,” he explains. “She needed one more song to finish the album. My boy Digi [Jameel Shams] hit me up -- he’s half Lebanese, half African-American, from Chicago -- he produces all the Khalid stuff.” Rohaim is, of course, referring to Khalid, six-time Grammy nominated RnB and pop singer, perhaps most known for his hit 2017 song ‘Location’.

It takes a second to distance my mind from the astounding casualness with which these names are said. It’s like someone telling you they were just having breakfast with Michael Jackson. Rohaim continues: “So [Digi] had sent me a bunch of loops a while back, and myself and other collaborators sit down and just flip these ideas. We put drums on them and make full beats out of them. So he sent a pack of melody loops and we flipped 12 of them…I sent [Digi] all of them, and there was one in particular, which was ‘Love to Dream’. I literally got a phone call the day after I gave them to him and he was like, ‘We got one on Doja Cat.’”

How did that happen? This is where opportunity, meets preparation, meets the thin strings of fate that intertwine according to God’s will. Digi had sent the beats over to Kurtis McKenzie, a frequent producer for Doja Cat, working on the ‘flip’ with other producers.

“This is just the producer network,” Rohaim explains. “There will be three to four producers on a song. One will add a melody, someone else will help with another melody, someone will figure out the arrangement, another did drums. And then someone else is in the studio making the song with Doja Cat.”

A long and complicated process, but a beautiful thing, to know that one song, adored by millions, is the brain-child of so many creative minds. But what of ego? Does that ever get in the way?

“The great thing about the friends I work with is that they know how to keep their ego in check,” Rohaim explains. I became curious as to Rohaim’s personal experience with ego. After all, he is notoriously known for being one of the first producers to bring ‘vocal chops’, the process of cutting up vocals and rearranging them on the beat, to mainstream music. In fact, his main contribution to Rihanna’s ‘Needed Me’, who the nine-time Grammy award winner has dubbed as one of her favourite songs, was adding vocal chops to the hook. And yet, it’s renowned producer Mustard’s tag we hear on the intro of the track, who Rohaim worked with frequently between 2015 and 2016.

“Do you ever feel like, “Damn, I wish people knew I was a part of this?”, I ask Rohaim, a little hesitantly, not wanting to discredit his work. He’s prepared with his answer.

“Right. That’s when the shaytan comes and whispers into your heart,” he laughs. “My life motto now is, nothing matters besides your deeds… as long as I can keep working, and my circle knows me, and the people in the industry know to come to me for the specific things I do, then I don’t have an issue. Recognition is a battle with every producer. There’s definitely emotional attachment to your intellectual property, and you have to be levels above your ego to be able to control that.”

Not always easy, but thanks to Rohaim’s faith, spirituality plays a large role in grounding him. “When I think about things that are not in my control, that start to eat me alive, I make wudu and pray ra’kaatein, and think ‘God created all these people.’ And… I completely let go. It’s all about tawakkul,” the Arabic word for the Islamic concept of ‘trusting in God's plan’.

Trust in God’s plan, and talent cultivated over years of practice. So what of his process as a producer?

“I have extreme ADHD so sitting in front of the computer helps me a lot…most times I’ll just sit down and play around on a piano… I’ll end up writing a chord progression… sometimes I’ll start with a drum loop… and then I’ll go through all the other melody loops that I have and see what fits… it’s very, very different every time.”

It’s important to note here the distinction between making a beat, and producing a song. The latter implies a more collaborative, in-depth process, based as much on energy and intuition between people in a room as it is based on technical skill and working with technology. As a songwriter who has cultivated entire careers, most notably with Australian superstar Kid Laroi, Rohaim’s prowess lies within driving a session, his ability to bring the best song out of an artist’s creative repertoire.

“If I’m working one-on-one with an artist, I just try to cater to them, as far as the process and how they like to make music,” Rohaim says. “With the music we make though, I like to get them out of their comfort zone. I want to make them uncomfortable, to make something different they’re not used to making.”

This, however, does not mean that artists are ever forced into a space they don’t like. Rohaim is very comfortable with making mistakes or trashing an idea that doesn’t immediately resonate with him and the artist he’s working with. “I hate forcing things,” he says adamantly. “If there’s no flow, then we’ve gotta dump it.” Though this implies that Rohaim’s process resides in a space of metaphysical intuition and ‘channelling’ creativity, he assures me that there is often a formula involved in the process -- one founded in scientific musical theory.

“I went over to Romania and I studied with a doctor of melody, Marius Moga. He taught me so much about melody in songs and how important that is… So while the artist and I are creating, I’m doing all that stuff in my head. I’m calculating how many syllables does this hook have…does this melody feel right? So I’m doing the technical stuff while the artist is just enjoying the energy in the room.” Rohaim shares that his goal is to help an artist write the best song they’ve ever written which, aside from being a hit, Rohaim refers to as the song that the artist resonates with the most, feels represented by the most. This, however, is not the ultimate goal for the rest of his life. He admits that he wants to eventually stop music -- and when he finds his exit, he will.

So what, then, is Rohaim’s true internal calling? If music started as a means to an end for the hit-maker, and continues to be, what is the end? “All this means to me is if I’m able to help my family, then I’m really happy. That’s all I want to do. I want to change the trajectory for my progeny. That’s my main goal.”

- Previous Article test list 1 noise 2024-03-13

- Next Article Wegz Collaborates With Ash on End Of Summer Smash Single 'Amira'

Trending This Month

-

Feb 20, 2026

-

Feb 09, 2026