Architect Bernard Khoury on the Myths & Meaning of Beirut’s B018 Club

We spoke to Lebanese Architect Bernard Khoury on his rise to fame through the underground B018 club, the birthplace of electronic music in Beirut built on the site of a massacre.

This is the story of a club that’s invisible by day, but comes alive at night. The story of a building that, for 26 years, roared with life, bass and provocation. The story of a door where Naomi Campbell once waited a full 30 minutes.

It’s the story of the birthplace of electronic music in Beirut. It’s also the story of a massacre.

In 1998, architect Bernard Khoury built club B018, which became an iconic globally-recognized party destination. A Harvard graduate and founder of the Beirut-based DW5 design studio, the Lebanese creative is known for his provocative projects.

Khoury returned to post-Civil War Beirut in 1993 with hopes of reconstructing not just the buildings, but the nation as a whole. When he didn’t receive the social restoration projects he yearned for, he was commissioned to build a different kind of social institution - a nightclub. Khoury chose Karantina, or the Quarantine, as the location of his first-ever built project - a neighborhood that right-wing Christian militias burned to the ground when the civil war started 20 years earlier.

“I felt that building a club on that site was very problematic,” Khoury told SceneNoise. “Nobody told me that, I just felt it.”

The Saudi-brokered Taif Accords brought an end to the 15-year Lebanese Civil War (1975-90), which claimed the lives of over 100,000 people, turned neighbors into enemies, and reduced historic architecture to bullet-riddled rubble.

“Some of us thought that the war as we knew it was over. I had my doubts about that. Obviously there were deeper, more complex political issues that were unsolved.” Khoury, then an enthusiastic architect in his early 20s, wanted to tackle these questions through architecture. “I deeply believed and was convinced that architecture was, and is, a political act.”

In the absence of state institutions, Khoury received commissions from the private sector—but not one of the 16 commissions over the course of five years came to fruition. “They died indoors and remained on paper,” he said.

Khoury expected social housing projects, museums, operas, and schools, but the opportunities never came. Instead, he got a nightclub, the only sector that entrusted him to build.

“You wouldn’t think of a nightclub as anything that could have any sort of political relevance, as they’re usually tucked underneath buildings,” he said. “Yet, I thought that even this could be meaningful, not just a frivolous, light, temporary architectural act.”

The next step was finding a location. With little means, Khoury couldn’t find a place in the prime areas of the city. So they began to search the fringes of Beirut, where he noticed a peripheral region close to the city center that looked like a “black hole.”

It was the northeast, port-adjacent neighborhood of Karantina. Originally the Ottoman-designated quarantine for ships coming into Beirut, it turned into one of the world’s first refugee camps for Armenians fleeing from the genocide (1915-17), and later Palestinians fleeing from the Nakba in 1948, followed by Syrians, Kurds, and Lebanese Shia from the south. When the Green Line split Beirut, Karantina fell on the Christian-controlled east side, despite its largely Muslims and Palestinian population. In January 1976, right-wing Christian forces stormed the shantytown, killing between 600 and 1,500 people.

Directly on the other side of the devastated neighborhood stood the bustling area of Little Armenia. “The project started there - with the absence of building, with the contrast between density on one side and void on the other.”

However empty the site itself, it sat on the edge of a busy highway - what he called the most important vehicular artery that links north to south. The noisy billboards and cluttered buildings along the axis sought visibility for profit, Khoury said.

So, he decided that his construction should disappear underground. Khoury was convinced that invisibility would make him more visible.

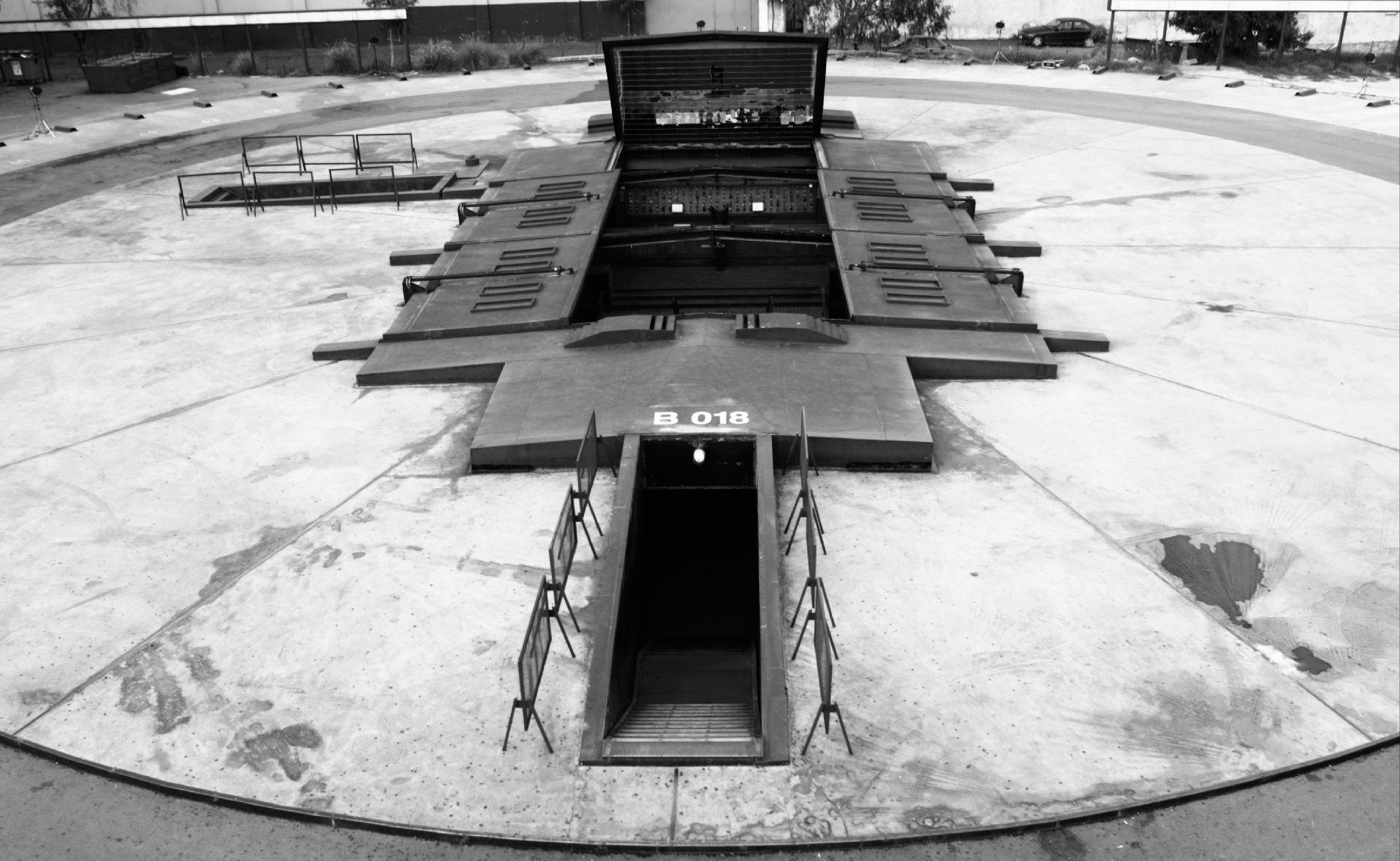

Often compared to a war bunker, B018 lies in the middle of a concrete disc that evokes a helicopter landing pad. The circumference is a parking lot that frames the club with a tarmac ring, cars moving in a carousel formation.

“When you enter the parking lot, you’ve already entered the club,” Khoury said of his design choice. The structure is only slightly visible above ground. With few surrounding buildings, Khoury wanted to open B018 up and let the music propagate. At night, the roof retracts, revealing an ethereal Beirut sky to the crowds beneath.

The architecture lends itself to an immersive experience with the city and the music. One of the panels that flips up is reflective, made out of small sections of plexiglass. “It gives a liquid image, an immaterial reflection of the movements and lights below,” Khoury explained.

From the ground level, a staircase descends to scowling bouncers below. The interior design has changed throughout the years - a 2019 renovation replaced the original mahogany furniture with solid stone boots and podiums - but throughout it all, B018 maintained a gothic, brutalist style.

However, Khoury did not always agree with the media’s narrative of B018.

“I was labelled the architect who dances on graves,” he said of the “macabre angle” the press emphasised. “A grave, a bunker-it wasn’t really that. It was a difficult task of bringing life to an area without falling into the amnesia common in the post-war 90s.”

“Maybe I should tell you the story of the name,” Khoury began. In the early 80s, he moved north of Beirut to the seashore and away from the war. His cousin Naji Gebran, a musician, moved into a studio in the same apartment complex with a collection of 3,000 vinyls and a sound system. The 30 square meter flat turned into a place for what he describes as musical therapy sessions. They stayed up until the sun rose listening to music against the backdrop of war. The club took its name from the apartment number: B018. For the first five years after opening, Gebran was the only DJ at B018.

“The beginning was literally a temple of music,” Khoury said. B018 didn’t follow trends, it set them. In 2024, Khoury said the club closed its doors due to financial mismanagement. He hopes for a revival, but he wouldn’t want to see it done the wrong way, namely as a commercial enterprise looking for quick profits.

“We were never there for the money,” he said. “But if it dies and doesn’t come back to life, what it gave was already fantastic and beautiful.”

- Previous Article Shuffle | Oct 16 - Oct 29

- Next Article SceneNoise x Beyon Al Dana Present Glass Beams & Yussef Dayes Oct 23rd

Trending This Month

-

Jan 29, 2026