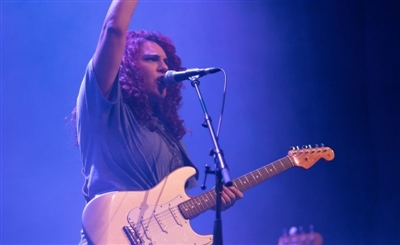

The Invisible Hands: the Future Sounds of Yesteryear

SceneNoise correspondent Kamila Metwaly gets up close and personal with the band that's putting Egyptian music on the global map, as their latest LP garners rave reviews from across the world.

Listening to Teslam by The Invisible Hands somehow throws you back to what many, including the band themselves, would call the golden age of music. On one hand, you connect with the album on many fronts, musically, lyrically, conceptually and visually, when you see the artwork. On the other hand, you are also aware that you like what you are hearing because somehow you are familiar with the sounds. You become eager and even pushed to dig deeper into your personal library of music, trying connecting the dots for yourself. Nevertheless, the music is simple, and the record feels like you are actually attending a rehearsal with them in the studio, and not listening to an album.

Teslam is the second LP released by The Invisible Handsthrough Abduction records label. International press including Pitchfork.com, Popmatters.com, Forcedexposure.com and more have critically acclaimed the album.

Their style is confined to Psychedelic Folk Rock, and that confinement is evident through both of their releases. They sing in Arabic and English, and consider themselves a non-sociopolitical group, even though many of their choices when it comes to, for example, album titles or their band name, are heavily associated with the current events happening in Egypt and the Arab region. It is unfair, though, to consider The Invisible Hands one of those bands abusing the previous and current sociopolitical climates to increase their likability. To a very large extent The Invisible Hands also seem not to give a fuck about those associations or referential art in general, and are keeping their focus on music making, and not politics. And as they claim via their Facebook page, The Invisible Hands are: “drenched in lovely Psychedelic Folk arrangements and vocal choruses with a nod to what could have potentially been music that surfaced decades ago but instead found its way into the future.” The band draws heavily from the past yet makes music in the present and embrace the “quality music, quality recording aesthetics” that has been long gone and replaced with the fast growing digital music industry in the world.

The band consists of five members, Alan Bishop (aka Alvarius B., member of legendary US band Sun City Girls and co-owner of the world famous Sublime Frequencies label), with Cairo-based musicians Cherif El Masri, Aya Hemeda, Adham Zidan and Magued Nagati. We met with The Invisible Hands to talk more about their music, their inspirations, and their new album.

Teslam is the latest release for The Invisible Hands. How do you feel about outcome of the record? And what are your personal reflections when listening to it now?

Cherif El Masri: Teslam is considered to be the first album for The Invisible Hands as a real band. Our first album was recorded in a verydifferent setting. We had to kind of pour our ideas together in this one. There was more of a cohesive unit operating when we were working on Teslam. So it has some songs that Alan wrote, some that I wrote, another that Adham wrote and generally we were all more involved in the process of laying down the tracks. I think it is a collective work that we’ve done through which we have also connected more, as musicians on a very interesting level.

What do you mean by ‘real band’?

Alan Bishop: The first record was a nucleus of Cherif, Aya and myself, then we found the drummer (Magued Nagati) who joined us at the last minute. We also did a lot of the overdubs ourselves on the keyboards and we weren’t actually a live performing band at the time. We have become a live performing band around five months after the release of our first album. Then, Adham joined the band, and finally we got Magued to be our fulltime drummer. Later we were able to rehearse together, play live shows, and so the second album came out of us being a real working band. We had all the instruments covered and it was a different process on the second album as Cherif said.

How long did you work on Teslam?

Cherif: It was recorded all together over two or three months.

Alan: The process took about six months something like that.

The sound quality on Teslam is somehow different from local Egyptian independent productions. Where was it recorded and how are you distributing the album?

Adham Zidan: Teslam and the previous record have been released through Abduction records; a record label based in Seattle. We are self-distributing the album here in Egypt, and the records going to US and Europe are going through the record label’s distributor, Forced Exposure.

Alan: We recorded in several studios in Egypt. The first album was recorded in ART Studios in Haram and the second was recorded at The Mix, which is in the Fifth Settlement. We used some proxy studios, Sonic near Mokatta, for example. So most of the recording took place in Egypt. The mixing and the mastering were done in Seattle. If I was in Cairo all year, I think we would do it all here but it is just the way that it happens. I have to manufacture and distribute in the United States and then out to the rest of the world.

Listening to Teslam felt a little bit like listening to an album record from a ‘live music performance’ aesthetic; especially when the two of the vocalists are singing together. How do you guys reflect on that?

Adham: I think it came out of us rehearsing together, and working so much on the live performance aspect because, at least when I joined the band, the songs already existed. And then it was about how to translate them from there onto the stage.

Cherif: And there is somehow the reverse of that process that we followed through with Teslam. Some of the songs were played live before we even thought to include them on the album. We really wanted to have the energy of the live performance in our record, feeling that something is getting across, not just record some project on Pro Tools with some infinite tracks. The recording aesthetic came from here; from our thoughts on how to play those songs live.

Post-January 25 Revolution, socio-politically driven bands singing Arabic Pop and Rock have been on a rise. Alan, why did you choose to create a band here? And what brought you here?

Alan: It wasn’t really a choice or a planned occurrence. I came here in November 2010 to play a show where I met Aya and Cherif. We discussed getting together again, I later went to see a rehearsal of the band Eskendarella, as they were in the group at the time, and then we met several times for coffee and we became friends. Loosely we discussed an idea of creating project together at some point and I didn’t know when was I returning. It was the first time I came to Egypt in 25 years; I was falling in love with the city again, for the second time, as I fell in love with it the first time I came in 1985. Then one thing led to another, we remained in contact through the first part of 2011. Then in the summer I got this idea, wondering will they be able to translate some of my songs that I didn’t necessarily have a home for, thinking that maybe they could work in Arabic. I started sending them songs, and they began translating and some worked really well but others were more challenging. I decided to come here in September of 2011 to start working with them on that idea, translating these songs to Arabic and then putting together a record. The first record was recorded in two languages and then it was the process of being able to figure out which songs to translate that would dictate which songs would appear on the album. I left Cairo in December 2010 without the intention of this to happen, so this developed naturally.

To what extent have your personal experiences with the Arab Spring become a latent inspiration in the composition of Teslam? And are your personal reflections to what has been happening in Egypt captured in the songs you’ve released?

Cherif: There is no way to avoid that, I mean we don’t live in a bubble and of course we also reflect upon various social, political, cultural aspects of the country we live in.

Alan: I always say that for me, it also affects the logistics of having a band in this city. Cairo in general is a difficult city to navigate, in terms of putting things together; we have to get seven people together on one day in a location that is away from where everybody lives, so we have to arrange to do this. And then, everyone has his or her own reality going on with multiple projects. Just to negotiate the basic fundamental manifestation of a recording session, or a rehearsal, is a difficult proposition sometimes. As far as the music is concerned, a lot of these songs I wrote well before 2011, so if there is any kind of similarity to what might be interpreted politically, socially or culturally, you could just say that it’s coincidental. It could maybe represent the fact that things are similar in other ways in different times in different places on this earth. So they could apply in the states, or in Europe, or in Asia, or in Africa in any period of our lifetime.

Adham: I also think, that you as a listener, you also project your own circumstances onto what you are listening to.

“Eyes in the Back of your Head” is very interesting mix and match to me. A ballad that somehow took me to Poland or Slav folklore. Yet, I also felt that the violin also interestingly hinting on Arabic music…

Alan: The root of the song is a traditional Hungarian melody and progression that is common throughout Eastern Europe. And because of the influence of Arabic music in that region through history, it all blends together quite easily. Whether or not Eyvind [Kang, the violinist] was playing Arabic scales, I am not sure what his mentality was going in, but he is playing to enhance the music in his way. I suppose it could be interpreted to have an oriental feel, it’s ambiguous if you know what I mean.

Cherif: The violin was actually the only instrument recorded outside of Egypt; it was actually recorded in the United States by a non-Egyptian.

On “Over Easy” and other singles that appear on the album, the keyboard sound feels highly inspired by The Doors…

Adham: Are you calling me Ray Manzarek?! Well, it is hard to describe the process of the making music. For me, the way I approach music is really kind of an organic situation. Whenever I try to analyse my work, I get into a different mindset, but making music is more experiential and for me music is more about creating something with other people. If I had to put that process into words, or break down the choices I make, then I could tell you that I feel that I am filling the soundscape I am surrounded by and I reflect on that soundscape specifically. I do not sit there thinking where am I going next with a certain song. I don’t approach music from a clinical perspective. Look, it is not just The Doors; the organ was used very much more prominently in music from that particular time period than it is used now. Whatever your reference is to music that’s made in the 60s - yours is The Doors so that’s where you go – there is a link between the organs and that particular time period, but I think that that specific time period is also what our common ground is, because that was the epitome of so much good in music.

Alan: It is true, I mean there was much more happening, and it was a much more exciting time, socially, culturally, musically there has been so much more experimentation happening in a more accepted popular music feel, than there has been since. Much more obscure artists could get regular contracts and be played on the radio whereas today it is just impossible. Today everyone is a musician, everyone is a photographer, everyone is a writer with a blog or Facebook, everyone is a filmmaker with a small camera, so things are diluted now. And that’s it. The rest of it is the independent world, and the independent world is wide open and it is very difficult to get an edge and get an audience, because you are competing with so many more entities. Adham is right, we do utilise a lot of the instrumentation, the tones, some of the recording techniques from this period because it’s a really fascinating period of studio production and there seems to be a lot more freedom in the music, in terms of possibility. I think these guys (Cherif, Aya, Adham) are very well established in researching in this period and getting way deeper than most in terms of looking for inspiration and ideas.

Is there a specific statement that you are intentionally making through your music?

Alan: I don’t know if there really is a statement.

Cherif: There is a record!

Alan: It’s all just a natural form of expression, and then people can read into whatever statements they want to get from it. And for us, we just do what we do, and there is no agenda, no message, and no statement. I mean, I think its either all self evident and perceptible for anyone in his or her own way. Everyone is going to take it differently anyway, and there is no sense to be absolute about it.

But I also think that calling the album Teslam is a big statement on its own because you are drawing from a certain culture, which is fine, yet you cannot neglect the fact that anyone grabbing your album from the region will associate that word with a certain statement…

Adham: But Teslam means thank you. You have a particular reference to where this word is put because maybe that’s the most popular or common reference for you. You’ve heard this word being used, and the word is just being reclaimed. And if you want to read into it and think that it’s some kind of a statement, then that’s fine.

Alan: Maybe some people will think that Adham sounds like Ray Manzarak, but maybe he sounds more like the guy from Procol Harum or maybe somebody else. Therefore all these comparisons are also pretty much personal to the listener.

I am highly intrigued by the artwork of the album. Tell us more about it?

Alan: Originally, these two collage paintings were supposed to be the artwork used on the first album. I met the artist, Monica Rene Rochester, who ironically lives in Seattle. She worked for a friend of mine and I bought the art from her so I could use it. Then, we decided to go with the graffiti instead on the first album, and I think it fits it quite well; we really love the art on the first record as well.

Adham: Alaa Awad, the graffiti artist, made the artwork on the first album; which was a part of a mural he painted on Mohamed Mahmoud.

Alan: As for the second album, we felt that this artwork finally matches our current works, so we are happy that we waited with the artwork for our second album. This is sort of how things happened, I mean when you make a record and you need to go through the system of everything that it takes to actually produce a record, manufacture it, release it, distribute it, deal with it, you come to the inevitable moment of “What are we going to do with the artwork? What are we going to do with the cover?” So its one step at a time, and then everyone kind of works together to reach a conclusion, so it’s just a part of the process.

The Invisible Hands documentary… When are we expecting that to appear and what is it about?

Alan: Currently it is still in progress; it is really hard to determine what it is because there isn’t a sequence that we can see. However the two filmmakers have been working on it since the spring of 2012 and they are from Greece, Marina Gioti and Georges Salameh, and they are still working on it. Probably I would say, that my estimation now is that it would be finished by the end of next year, perhaps.

So is it documenting everything that you have been doing since spring 2012?

Alan: It’s documenting a lot. It is impossible to really know how are they going to present it because I think we are also all collectively involved in the making of this film. And it is yet to be realised as actually what kind of a documentary it is going to be. I really want to make sure that humor is injected in this film because I think we are all very humourous people and humour is always the best way to express ideas in my opinion.

When will we see you again live?

Adham: In the spring; unknown location and time though. Sometime in April or March, we don’t have anything booked yet. For the time being, we are trying to establish a network to distribute the record here. Currently it is in Balcon (Heliopolis), in 100Copies (Downtown), The Room (Garden City) and Sufi (Zamalek). It’ll pop up elsewhere around town soon too.

Find The Invisble Hands on Facebook.

Photography by Shady Habash. Main image courtesy of CairoZoom.

- Previous Article Getting Abyusif

- Next Article DGTL: Much More than a Music Festival

Trending This Month

-

Nov 24, 2025