Radio Al Hara: The New Online Radio Station in Palestine Playing Music from the Margins

In light of a growing trend of internet radio stations emerging from the stillness brought about by the coronavirus pandemic, we speak to the founders of Palestine's Radio Al Hara, which in a matter of 3 weeks, has amassed a global following.

While our Instagram feeds continue to flood with live streams, there’s a growing desire for a less imposing form of entertainment - something to connect us to others, yes, but also something that is slightly more non-committal. Around 3 weeks ago, our - or maybe it’s just my - prayers were answered in the form of a growing trend of online radio stations, born out of the quarantine ushered in by the coronavirus outbreak. The trend started, at first, all the way in Italy with ‘Radio Quartiere’ and rippled across borders and continents to find a place in Beirut, Tunis, and in two homes between Ramallah and Bethlehem.

We decided to zoom in on Radio Al Hara, the latter and most recent addition to the trend, but one that has gained a handsome number of followers, and as handsome an amount of participants, in virtually no amount of time. Attributing their rapid rise to popularity to their striking visual presence, courtesy of Amman-based designer Mothanna Hussein who later joined the original three, siblings Elias and Youssef Anastas, and Ramallah-based visual artist Yazan Khalili, who lead the platform along with DJ and graphic designer Saeed Abu-Jaber, the station draws on all of their unique backgrounds, both within the MENA’s music scene and outside of it, to create a multifaceted cultural space emerging out of “isolation and boredom, a time where the future of the world as we know it remains unknown.”

“We will open this space for listening, discussion and debate, so that we can spend isolation communicating with each other and remembering one another,” they write on their webpage. “We hope this is the beginning of a collective space that will continue once this world crisis is over… stay tuned, from the bedroom to the living room, and the other way around.” The internet station exists within a larger platform, Ya Makan, initiated by Beirut’s Radio AlHai. Ya Makan features a number of other stations including one in Tunis called ‘Al Huma’, one in Berlin, and another in Syria.

"Being in the context of the Middle East now with the coronavirus outbreak, it's very hard to stay in touch and connect with other people, at least in person, and the radio is a medium that allows connection,” explains Elias from his home in Bethlehem - a city in the occupied West Bank, which has, for decades, been under a ‘lockdown’ that, in many ways, draws a resemblance to the state of the world today. “The idea of the radio is to defy borders and open up the platform to anyone who wants to share their cultural and musical production. It’s a platform open to everyone,” he continues.

The name ‘Radio Al Hara’ is reflective of the nature of the station - it is a close-knit community erupting from the margins, yet as Elias explains, extends to the whole world just by virtue of the unique moment we’re in now due to the emergence of a global pandemic. He says, “the whole world right now is sort of like a hara.” Although the universal element of the station is undeniable, the place it stems from is not only marked by a heavily socio-political context, but embraces it. “We’re not creating a cultural radio station about Palestine or an exclusively Palestinian radio. But we begin from this locality,” explains Khalil. “But that’s not our end goal, to teach the world about Palestine. Palestine becomes an essential part of the radio by virtue of our personal connections and network. It’s the central node where we meet.”

The daily programme of the radio station, which launched only a few weeks ago on March 20, goes from morning segments like the “ramblings” of Chef Fadi Kattan and his guests, who delve into the history of Palestinian food and how to make it; to sounds and records that heavily evoke the Global South - afrobeat, Latinx, dabke - many that are sourced by the creators of the radio themselves, particularly by Youssef and Hussein, who both boast an enormous collection of records, spanning the Arab world and beyond.

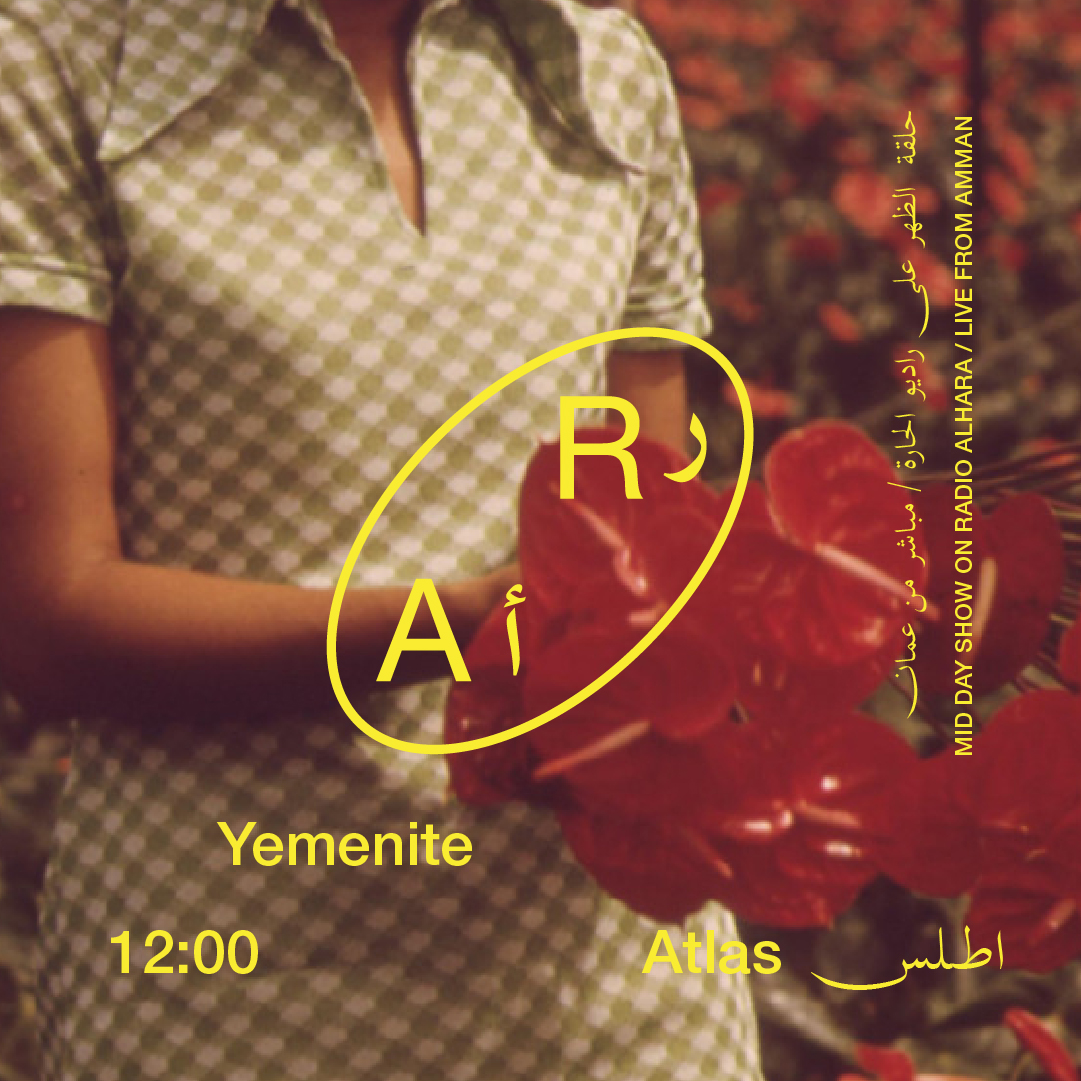

Hussein (alias Atlas) was one of the first to play his sets on the station, and along with graphic designer Saeed Abu-Jaber, his partner in Turbo, a Amman-based independent design studio, their music - ranging from funk, groove and jazz to Arab and oriental influences - was able to pave the way for what would become a haven for marginal sounds and voices, for music that comes from histories of socio-political struggle.

From the elusive sounds of post-shaabi Egyptian producer 3Phaz, to Turkish DJ Mehmet Aslan’s dance reworks of his own often obscure vinyl collection, the music they played "set a tone which other artists, not only in the region but outside of it, whose music is non-commercial, alternative, or has identity and character, became aware of." After that, "we get the sets and program it to the radio," explains Youssef. "It’s like an open and public platform in which anyone who's interested can participate."

In spite of the founders’ own rich backgrounds in music, and the contributions of some of the most promising emerging and established artists from the region - including Lebanese indie sensation Yasmine Hamdan - the founders insist that their interest lies in sound, more generally, rather than just music. Those sounds include, yes, some of the most noteworthy artists of the MENA region, but also the “ramblings” of chefs, folklore readings, oral histories woven in mesmerising tales by Palestinian audiovisual artist Jumana Abboud, and the musings of senior economist Raja Khalidi on the economies of the Arab world post-pandemic.

“The radio fills the soundscape of your home, but it doesn’t demand your attention and force you to sit down to listen to it,” explains Khalili. “It is very organic and adaptable to our lives at the moment. We’re using a Dropbox that’s open to everyone who wants to share their work or sets with us, we created a Gmail account, and all the social media accounts, so technically, we used all of the tools and resources we usually use in our day-to-day lives.” As for the musicians, artists and DJs who play live and recorded sets every day, they also use the equipment available at hand; mixers and software on their laptop, pianos and DJ controllers - which is then all broadcast through to the station. “The radio utilises the tools we all have at our disposal right now while we’re all stuck at home,” notes Khalili.

The four guys agree that the unique moment that gave rise to the station is also a large part of the reason behind its popularity. Hussein explains, “we keep gaining more and more listeners everyday because a lot of the people playing for us are actually quite big, and they’re people who, under normal circumstances, might not be available at all to take part in a project like this one.”

Online radio stations, then, at this time, present an opportunity perhaps unlike any the music industry has seen or will see - especially on local radio stations in the cities of the Arab region - of a connection between the eerily slow pace of the world at the moment, and the casual ambiance of a radio programme that showcases emerging artists’ voices and their similarly ‘slow’ and organic approach to sound, represented not only in the music they play, but in the ways they float in and out of the station to comment on the music or send messages of solidarity and hope to their listeners.

When it comes to the future of the programme, Elias says, “we’re definitely going to stay on, but how it will stay on and in what frame and how it will adapt, that’s something that will become clearer with time. We’re still experimenting and discovering our audience and the scale of our impact, and then, hopefully, we’ll know how to adapt and develop into a larger platform.”

You can follow Radio Al Hara's Instagram for their daily schedules, programmes and line-ups.

Image Credits

1. Youssef Anastas and Mothanna Hussein, (Photo courtesy of Sowt, Hussein and Anastas)

2. Design by Mothanna Hussein for Blastik's set (Photo courtesy of Elias Anastas)

3. Design by Mothanna Hussein for his own set. (Photo courtesy of Elias Anastas)

4.Design by Mothanna Hussein for his own set (Photo courtesy of Elias Anastas)

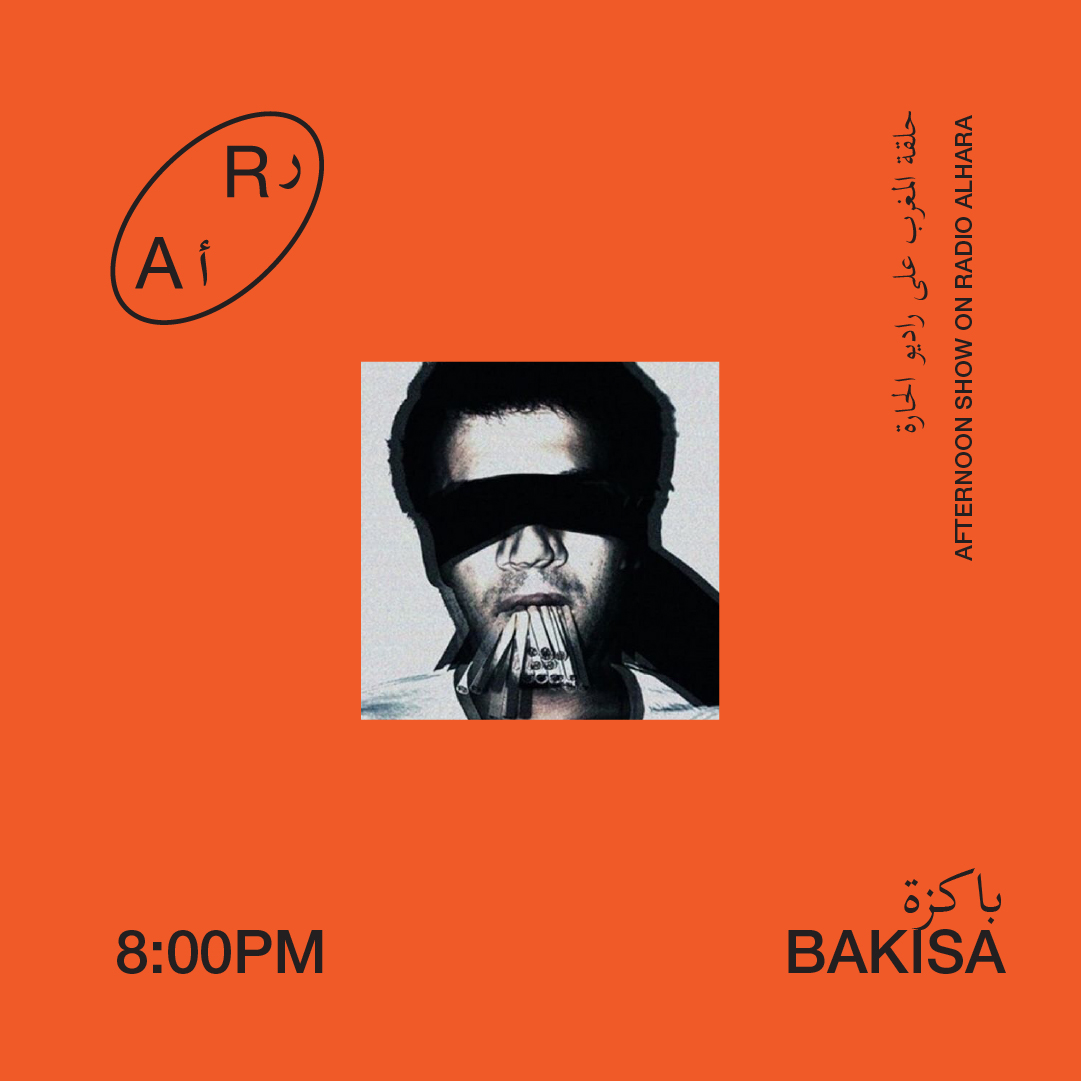

5. Design by Mothanna Hussein for Bakisa's set (Photo courtesy of Elias Anastas)

- Previous Article test list 1 noise 2024-03-13

- Next Article 23 Must-Watch Middle Eastern Music Documentaries

Trending This Month

-

Feb 20, 2026

-

Feb 09, 2026