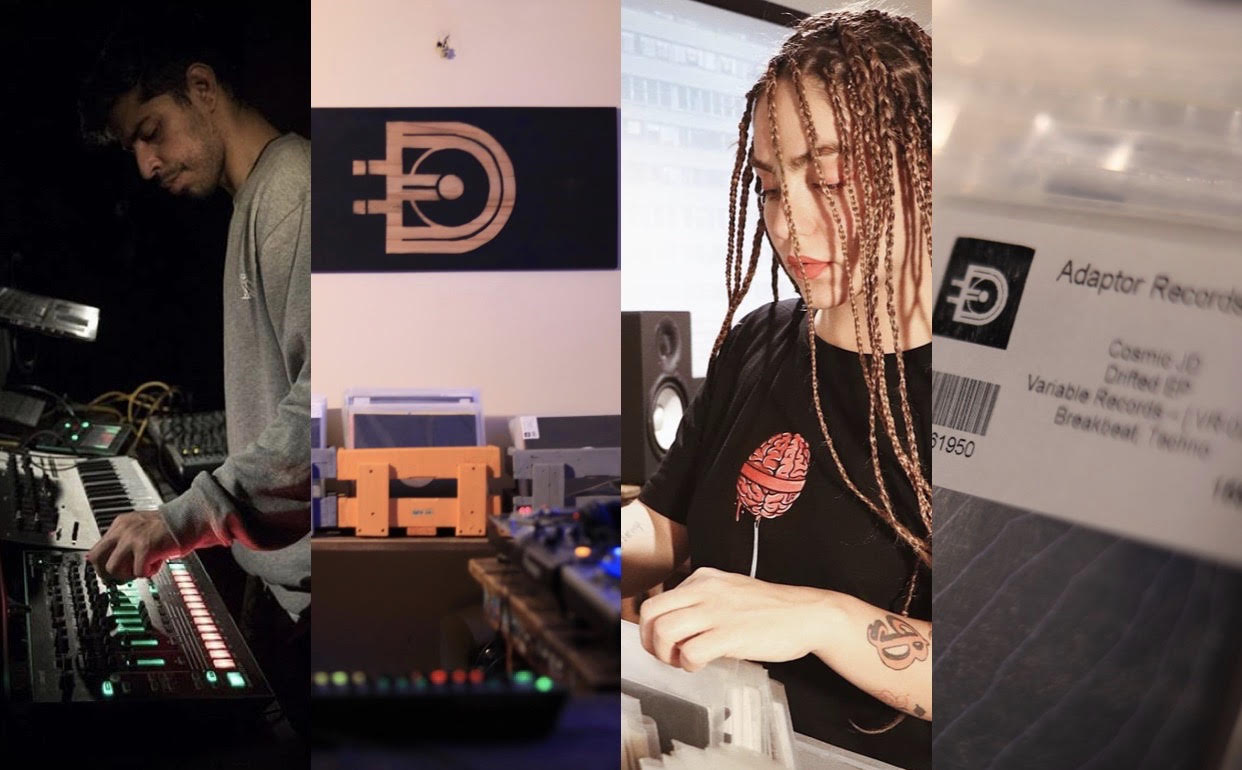

Adaptor Records Founder Amirali Hosseini on Techno, Community and Iran’s First Electronic Vinyl Store

The label co-founder and owner goes in depth on starting Iran’s first record store dedicated to electronic music, and breaking through to the global scene.

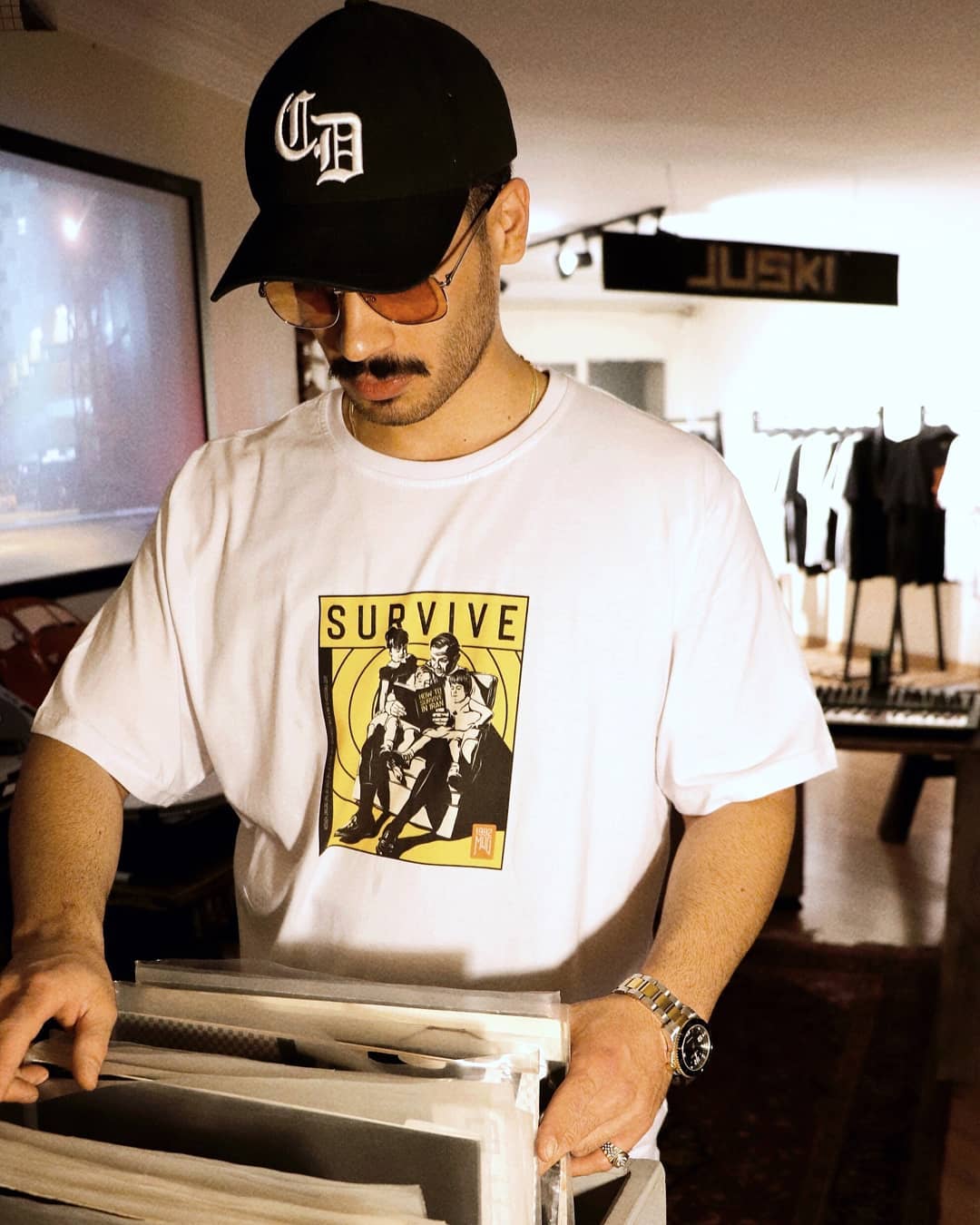

When one thinks of Tehran, a thriving electronic music scene is far from the first thought that comes to mind. Contrary to popular belief (and an overwhelming amount of western propaganda) Tehran has a burgeoning underground music culture that has been steadily breaking through to global recognition thanks to organizations like Deep House Tehran, Sampatik, and Adaptor Records (to name only a few). We spoke with 28 year old Amirali Hosseini, producer, DJ, and co-founder of Adaptor Records for an insider take on Tehran’s electronic underground and the ins and outs of opening Iran’s first record store dedicated to electronic music.

Who is the Adaptor Records Team?

It’s me, my partner Vahidreza Mahmoudi, and Shaheen Shayson, who’s our art director and [handles] all the artwork and videos.

What did the Tehran electronic scene look like before corona?

I think there were more than 20,000 people in Tehran that are involved with electronic music [across] many different genres, but everything is still underground. There’s a “pure” techno scene, a commercial techno scene, many people who are into psytrance/drum n’ bass and that kind of ’hardcore music,’ and there are about 4000-5000 people who just want to hang around and party but have no [real] idea about the music or [it’s history.]

Would you say that Tehran has a music infrastructure that supports this underground scene?

We don't have the same kind of industry for electronic music that [exists abroad]. But even though we don’t make that much money there are so many talented people who are very active [within the scene]. There are now 24-hour radio shows [for electronic music], and three or four labels hosting weekly podcasts. [At least before Corona] there were many events, but I dont think many people outside Iran know about this.

What was the initiative behind starting Adaptor Records?

There are so many talented people in Tehran. When I started Adaptor Records [a few years ago] I had the goal of showing the world that Iran has a high level of [musical] talent. Years ago there wasn’t [that much new electronic music coming from Tehran], but nowadays when you look up Iran or Tehran’s music scene there are so many results, and there are currently more than ten active electronic labels in Tehran.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/LZRH0MK74Ak" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

If you could compare Tehran’s electronic scene to any other city, what would you choose?

I feel like Tehran is like Detroit, in the sense that we’re working on music and partying but completely underground. I think if it was easy there wouldn't be such passionate artists active in Tehran’s scene. This hard lifestyle makes them more passionate about music, it makes them love music more and always try to be better.

What was the inspiration behind opening a physical record store?

It’s a long story. I was in Dubai working with Analog Room (Mehdi, Siamak Amidi, and Salar Ansari) and Mehdi — who’s like a brother to me — told me one day: “Amirali, you’re turning 30 [soon], you have to do something with your life. If you don't do something about it [you’ll burn out]. So when I came back [to Tehran] I partnered up with my friend Vahid Mahmoudi and we talked about starting a project together. After ten years in Tehran’s music scene we had made so many friends and connections, and they were all telling us to start a project together, so [it made sense].

Another friend of mine had just started a clothing company called JuskiMade, so we thought about opening a small shop together and making a space where friends of ours could [gather], spend time together, and start some kind of community. In a sense, our customers are our community. Any customer who comes to our store becomes part of the community, eventually the connection happens.

After we got the space, about a year and a half ago, we started Adaptor Records, with the goal of trying to connect Tehran’s scene with those in other countries. There’s a community of more than 80 people who play vinyl or have some connection with electronic music. So starting the shop made sense. At first Vahid and I put over 150 of our records in the shop, and had a turntable out so that people could come into the space and listen to music. After that people started giving us their turntables, speakers and instruments in order to sell for them, and things got bigger from there.

>Sometimes Vahid would travel to Istanbul, or Spain, or Germany and come back with more records. Sometimes artists in Tehran who wanted to resell their records would give them to us, and eventually we started having customers who’d show up on a monthly basis. There aren't many of them, but it’s enough for us, you know?

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/5ryoNkSkrFM" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

How difficult is it to get new vinyl to Tehran?

It’s not that easy, but this is the way things are right now, we buy vinyl from artists that we know and resell them. Before Corona we used to shop in places like Istanbul and bring the records to Tehran, or buy vinyl from artists that we know or artists visiting Tehran. Some people sell records in order to buy other records, so we ended up with a good collection. We’re trying to get more people involved in vinyl, but at this point in time with Tehran’s economy, people don't have the money to spend on records. It’s too expensive right now, but I’m hopeful that Insha’Allah things will get better.

Are there record stores in Tehran that focus on such a specific genre of music?

There are a few online vinyl record shops, for Iranian local music or more famous western records like Pink Floyd and stuff like that, but we’re the only record shop specifically for vinyl and electronic music.

Is there a particular style or genre of music that defines Tehran’s scene?

To be honest the main genre of music young people listen to here is hip-hop. But at least for electronic music I can't really say what's the mainstream sound of Tehran, there are so many spaces that play techno, spaces that play psychedelic music, or ones that play commercial music.

When I say “spaces” I’m talking about private houses where people gather with their friends to party, it’s not like clubbing. It’s also why people have such close communities around their particular styles of music. At least for “pure techno” I think there are about 3000-4000 people involved in that scene.

What are some recent projects you’ve been involved in recently despite corona and the lack of live events?

We hosted this “DJ duel” on Adaptor Records’ Instagram, where we picked 16 artists (who are all our friends) to “duel” each other on vinyl and share their music. They’d talk about the vinyl and the history of it, and because we were all friends we were laughing the whole time and having fun. We put it online and each time we had a couple of hundred people watching — which was really good for us — and when we had people like Nesa Azadikhah or people with a large following on the show the higher numbers were even higher. This was all at the beginning of this whole corona thing and we wanted to do something online that wasn't just a series of normal sets.

Any future plans for Adaptor Records?

So many plans. We’ve got some showcases coming up, two featuring music from Seoul, and another one from San Francisco with Ardalan, who’s been streaming on twitch with the collective GoodTv and we’re talking about doing something together For Adaptor. We’re going to start uploading live sets to our youtube, and for the record shop we’re trying to get it more online and let people be able to buy our records from our website. That’s at least the plan for these next couple months.

Check out Amirali’s thumping set for The Analog Room’s Tehran Showcase.

Follow Amirali on Instagram, Bandcamp, and Soundcloud

Follow Adaptor Records on Instagram, and Soundcloud

Follow the Adaptor Store on InstagramTrending This Month

-

Jan 29, 2026