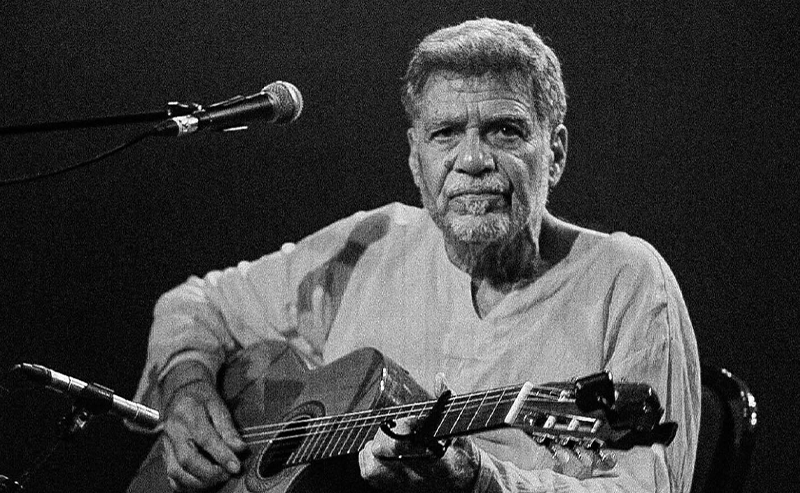

In Context: The Quiet Radicalism of Lebanese Musician Rogér Fakhr

Tracing the lost legacy of Lebanese folk musician Rogér Fakhr, shaped by war, displacement, and a body of work that refused to fade.

The story of Rogér Fakhr is one of those rare, quiet revolutions that never announced itself - a career that unfolded almost invisibly, only to resurface decades later as a missing chapter in the sonic memory of Lebanon and the wider region. While many of his contemporaries carved their names the country’s cultural golden age, Fakhr drifted in the margins, crafting a body of folk-driven, soul-leaning songs that never had the chance to reach their intended audience.

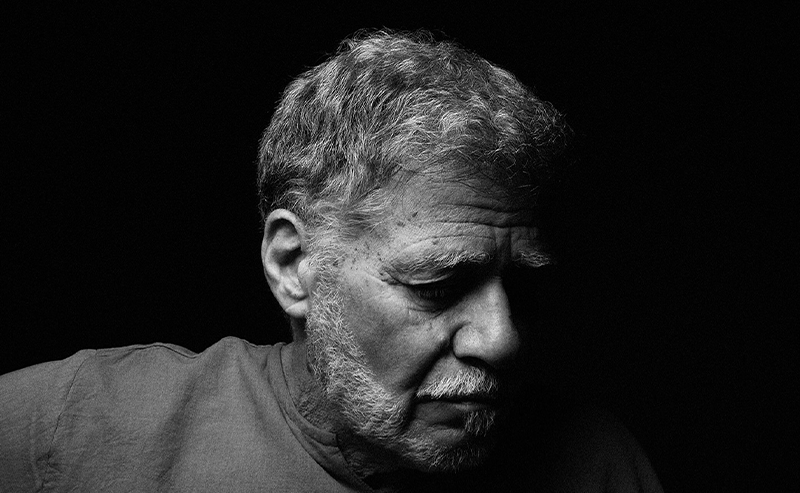

Half a century later, they re-emerged with a new lease of life, placing Fakhr as a Lebanese musician who intuitively understood global counterculture currents while remaining deeply shaped by the social and political fractures around him.

Born into a Beirut that pulsed with artistic ambition, Fakhr found himself immersed in the city’s 1970s musical ferment - a landscape animated by Fairouz’s mythic presence, Ziad Rahbani’s jazz-inflected satire, and a youthful generation reaching outward toward Western sounds. While others pursued the grand orchestral pop that dominated Beirut’s stages, Fakhr gravitated toward a gentler, more intimate style; finger-picked guitars, melancholic chord progressions, soft rock haze, and a lyrical sensibility drawn as much from American folk as from the emotional vocabulary of the Levant.

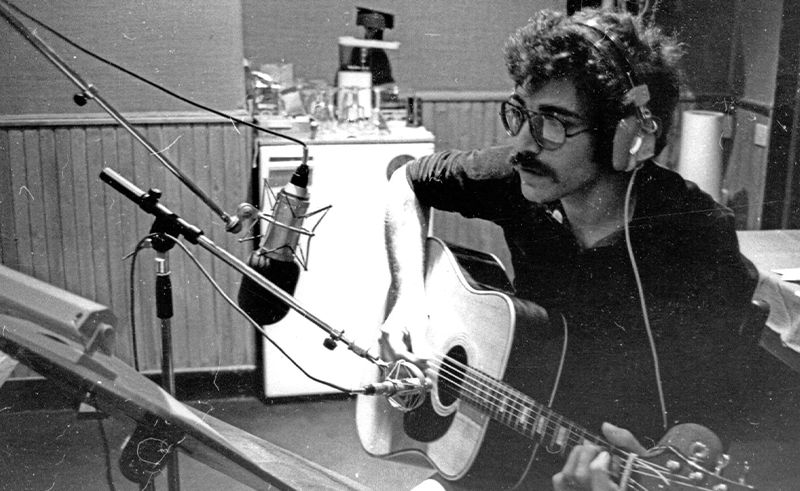

What sets his trajectory apart is not simply his sound, but the circumstances under which it was created. The Lebanese Civil War scattered artists, shuttered studios, and fractured once-vibrant communities. Fakhr, navigating this uncertainty, recorded songs in makeshift spaces such as apartments, borrowed rooms, improvised home studios. The music circulated in extremely limited cassette runs, sometimes no more than a couple hundred copies handed between friends. These tracks functioned like coded letters from a generation living through crisis - deeply personal, quietly resilient, stubbornly hopeful.

If many artists are defined by their breakout moment - the single, the performance, the spark that pushes them into public consciousness - Fakhr’s equivalent was the opposite: a disappearance. His recordings never broke into the mainstream, not because they lacked quality, but because the infrastructure around him collapsed. Where many artists chased visibility, Fakhr pursued clarity of craft, even as the world around him made it nearly impossible for his songs to travel.

But time has a way of unearthing what history buries. When Berlin-based label Habibi Funk reissued Fine Anyway in 2021, a compilation album of Rogér Fakhr’s recordings from the mid-1970s, the response was one of collective recognition; listeners across continents suddenly encountered a voice that felt timeless, unforced, and strangely familiar. Fakhr’s music carried the introspective warmth of 70s folk, the breezy confidence of Laurel Canyon soft rock, and the soul-streaked melancholy of artists who write from the edges of upheaval. Yet none of it felt imitative. Instead, it revealed an alternative vision of what Lebanese music could have been, had the war not cut so many stories short.

The reissue reframed Fakhr not as a forgotten footnote, but as an essential bridge between Lebanon’s storied past and its unrealized possibilities. His songwriting, understated but meticulously crafted, showed an intuitive grasp of phrasing and melody. His guitar work, patient and expressive, mirrored the emotional restraint of an artist who understood how to say more with silence than others could with orchestration.

Unlike many of today’s nostalgia-driven rediscoveries, Fakhr’s resurgence is not built on myth or retro fetishism. It’s built on the undeniable strength of the music itself. Tracks like 'Had to Come Back Wet' and 'Dancer' reveal a songwriter who absorbed global influences without ever abandoning the emotional textures of his environment. The intimacy of his recordings, once a byproduct of necessity, now feels intentional, like an analog minimalism that foregrounds voice, story, and sentiment.

The renewed interest in Fakhr’s work comes at a moment when the region is actively re-examining its lost archives, its underground histories, and the artists who slipped through the cracks. In this context, Fakhr’s trajectory feels symbolic. He represents the possibilities of a 1970s Lebanese counterculture that never fully materialized, interrupted, but not erased, by violent disruption. His music is proof that cultural memory is rarely linear; sometimes, it loops back on itself, revealing what the world failed to see the first time.

Today, Rogér Fakhr stands not as a rediscovered relic, but as a newly relevant artist - one whose work resonates with listeners searching for sincerity, texture, and storytelling outside the formulas of contemporary Arab pop. His career may not have followed the arc of traditional stardom, but it charts something arguably more compelling: the long, improbable journey of music that refuses to vanish.

And perhaps that is the true legacy of Fine Anyway: not simply a reissue, but the restoration of a voice, a moment, and a possibility that the region is only now ready to fully hear.

Trending This Month

-

Dec 24, 2025

-

Dec 23, 2025