How Mohamed Mounir’s ‘Shababeek’ Revolutionised Egyptian Music

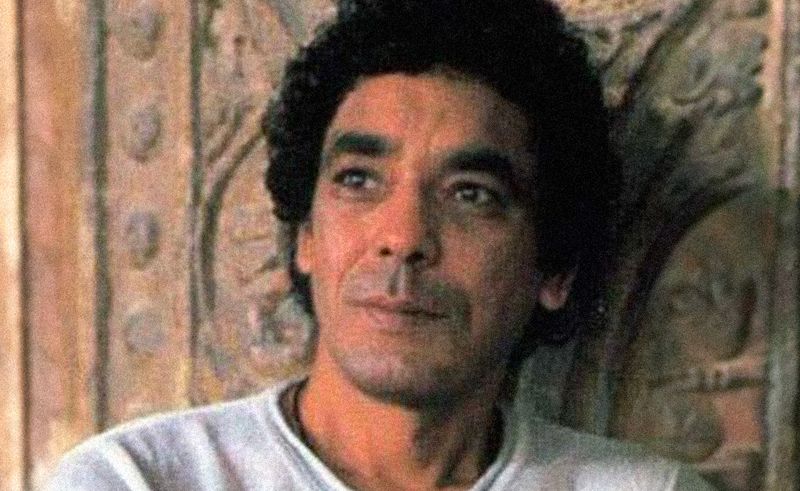

Also known as ‘El King’, Mounir’s Nubian roots created a fresh sound that blends tradition and revolution in Egyptian pop.

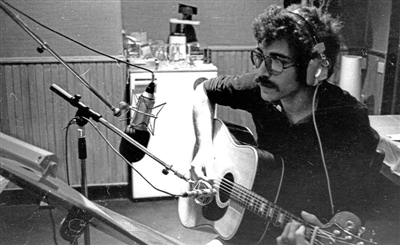

The year 1977 will forever remain pivotal in the history of Egyptian music, marking the release of Mounir’s debut album, ‘Alemony Eneeky’. A work that introduced a young, skinny, curly-haired brown Nubian man with a voice unlike anything they had heard before, who stood in stark contrast to the conventional, stereotypical image of the Egyptian singer. From the very first glimpse, he embodied the change that people had long been waiting for. Decades later, the people crowned him with the nickname ‘El King’” with his music passed down from one generation to the next, eventually becoming an inseparable part of Egypt’s cultural heritage.

Most of us have been raised in families that adore the king’s music and memorise each of his songs wholeheartedly, from 'Amana Ya Bahr’ to ‘Ya Layali', with many of his records decorating our musical shelves. The record that still intrigues many the most, however, is his 1981 studio album 'Shababeek’. Our reception of this album, as a young generation, has constantly changed throughout the years, from obsessed kids who're just repeating its lyrics without substantial understanding, to an admiring new generation that is very curious to find out more about the dexterity behind this musical achievement.

‘Shababeek’ was recorded at the onset of the cassette and tape era, when the music distribution business was radically changing - along with shifts in musical genres, as the people felt the need for something new. All of these factors combined played a major role in the massive success of what is arguably El King's best-ever album, and one of the best Arab and African studio albums ever recorded. Mounir’s third album was a very natural reaction to the immense changes Egypt underwent in the 1970s. These began with the death of President Nasser, marking the end of the socialist era, and continued with the rise of President Sadat, who embraced capitalism and a free market economy. Mounir and his generation lived through this transformative period, which not only reshaped Egypt politically and economically but also profoundly impacted art, culture and society as a whole.

Mounir’s third album was a very natural reaction to the immense changes Egypt underwent in the 1970s. These began with the death of President Nasser, marking the end of the socialist era, and continued with the rise of President Sadat, who embraced capitalism and a free market economy. Mounir and his generation lived through this transformative period, which not only reshaped Egypt politically and economically but also profoundly impacted art, culture and society as a whole.

‘Shababeek’ was a very provocative album upon its release as it was way ahead of its time, a fusion of Jazz, Reggae, Pop and Folk with a Nubian blend in an unprecedented harmony, thanks to the incredible execution by the jazz enthusiast Yehia Khalil and his band. It was the album that introduced Mounir to the public as an innovative pioneer and someone who has something to say - something that was completely unheard of up to that point.

El King’s 1981 album was a sincerely authentic reflection of his Nubian roots and his transition from Aswan to Cairo, as his family was forced to relocate to Cairo, when his village was destroyed in a flood following the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Yet, Mounir brought his roots all along the way with him, bringing a brand new sound to the Egyptian pop scene, a sound that carries tradition in its essence and revolution in its pursuance at the same time.

To complement this peerless sound and voice, Mounir ensured collaboration with top-tier Egyptian songwriters like Abdelrahim Mansour, Fouad Haddad, Magdy Naguib and Shawky Higab – poets deeply connected to the Egyptian street, its problems and underlying struggles. The same applies to the melodies, with Mounir collaborating with some of the greatest Egyptian composers of all time, such as Baligh Hamdy, Ahmad Mounib and Yehia Khalil himself.Each and every song in ‘Shababeek’ holds a story within its melody and lyrics, from 'Shagar El Lamoun' that addressed the Palestinian cause, ‘Shababeek’ and the detention period of its poet Magdy Naguib in the Nasserist era, 'Al Madina' and the false fantasy and fallacious imaginations around the city. 'El Leila Ya Samra' spoke from the heart to Egypt herself, while 'Ashki Le Meen' reflected the struggles of a young man in times of uncertainties and radical change, and ‘Al Kon Kolo Beydoor’ covered the complexity of the human condition. Shababeek still remains a depiction of many controversies. Whether societal, political, humanitarian or emotional, it's a sketch of our profound thoughts, pain, joy and broken dreams.

Mounir previously mentioned in an interview with Omar Taher that he wanted to end the centrality of Cairo in Egypt’s music industry, which is something he manifested throughout his whole career. He wanted to give a voice to all the people of Egypt; he wanted Egypt’s music to be filled with the spirit of all of its cities and villages and not to let the Egyptian music scene represent the people or character of a particular city. Mounir was a legitimate artist, not just a craftsman, and he was fully aware that Egypt’s musical heritage was extremely rich that it was the raw material for an unrivalled inventive and creative space, and that reducing it and restricting it to specific sounds would be extremely unfair to this ancient culture. Mounir carried the concerns, burdens, and dreams of an entire generation that always wanted to change Egyptian music but was afraid to take the initiative, and his arduous journey from Aswan to Cairo brought him to the hearts of all of Egypt’s people.

Trending This Month

-

Dec 24, 2025

-

Dec 15, 2025