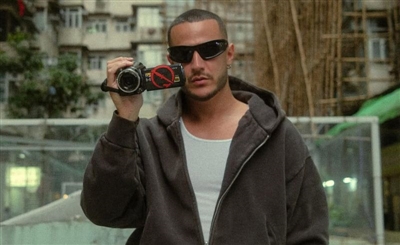

Noise 101: James Zabiela

We sit down for a fascinating talk with one of the world's biggest electronic music innovators following his gig in Cairo.

In music and the arts, the word 'guru' is thrown around all too easily. One man who can definitely justify the title, however, is UK DJ and producer, James Zabiela, who some have even gone further in crowning him a 'technical Jedi'. High praise, indeed. The Brit doesn't only push the boundaries of DJing to their limits — he creates them, quite literally, as he took part of the creation and firmware development of much of the equipment that are now an industry standard.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/Gkr4bXDpPLU" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

We sat down with him following a memorable gig in Cairo, where his energy dominated the wide, green open spaces of Royal Mohamed Aly Club and his music tore it apart, so to speak. The enthusiasm that oozed out of him was that of a kid playing with toys (more on that later), and the crowd was, in no uncertain terms, feeling it. It was when we sat down with him that we discovered that he really is kid at heart, full of enthusiasm and wanting to do one, seemingly simple thing: to play good music.

As a DJ who started his career playing on turntables, how was the transition to digital? What finally pushed you to switch?

It was really difficult. When I used to play vinyl, I was such a physical DJ — you jump around, put record sleeves left, right and center. I would turn the DJ booth into my messy bedroom. I loved the whole physicality of it and not knowing the names of all the tracks. I’ve ruined all of my records because I wrote on all of their labels. I still buy a lot of vinyl, but they’re in pristine condition because I don’t play them as much. The hardest part was figuring out a way to organise all my music, which I still modify all the time. Now the USB can carry thousands of tracks, but all you do in a gig is scroll through them while looking in a screen for two minutes. Some call it 'Serato face'. Vinyl is more fun. There’s no screen and you’re more connected to the music because you have to listen. You’re just using your ears and that's where all the focus is.

You say this, but you've also had a hand in the transition to digital...

Yeah, maybe a bit. I’ve worked a lot on a lot on the firmware modifications of some of the Pioneer equipment. When the CDJ 2000s first came out, the head of product planning in Europe came with me on tour, and we had them in flight cases, testing them before they came out and fixing all the firmware bugs. We waited for things to go wrong during the gig so that we could fix them. It’s actually insane to think about, because I wouldn’t do this now. I was just a bit more carefree when I was younger. I was once at a huge festival and the thing just crashed. I was like “Sorryyyy, just give me a sec, I’ll reboot the thing now.” So, I do feel like I contributed a little bit. That was the time when a lot of people were shifting over to laptops, and it became very trendy to play on Traktor. If they didn’t nail the CDJs in such a way…

What? Turntables would’ve died?

No, but I think that they would’ve maybe captured more of the market share. I also worked a lot with the RMX effect unit. That’s the kind of thing that I love to mess around with, because I love toys. Nowadays, Pioneer make 100 products a year, everything from midi controllers to toys for kids in their bedrooms. But I have a job: DJing. Maybe when I retire I’ll try to get a job there.

Hmmm, interesting...what was your involvement in developing the RMX?

Well, I pretty much used the EFX 1000 to death, so they wanted to make a follow-up to it, and I worked a little bit on that one, firmware-wise. But it was just an improvement of the EFX 500. I remember they sent me an initial unit which didn’t really work at all, but had basic firmware. So I didn’t really design it or anything.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/Ibnv-a5vJsA" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>How do you balance playing with effects during your set, without overwhelming the crowd?

I did that for a long while. You know when you get a new toy and want to play with it all the time? It took a while to restrain myself, or use it in a subtle way. Sometimes I play and people are like, “you didn’t really use the effects much tonight. I came to see you play your super Nintendo.” I just found ways to make the effects really help blend mixes and do subtle things, rather than spontaneous effects in the middle of the track just for the sake of it. I’m still a showoff, but I was definitely more of a showoff when I was younger.

Speaking of 'when you were younger' (well, a little younger than you're referring to), we understand that your dad was a raver. How did that influence you growing up and getting to like dance music?

I think if anything, it pushed me off. As you do, you rebel against your parents. Around 1992, he’d be going out to these illegal raves in fields. He’d just get in the car and tune the radio to get the location. So he’d do that and come home on a Sunday afternoon still awake, and I’d be seeing reporters on the news talking about evil rave music and evil rave culture and illegal parties. It was on the front pages of all the newspapers - 'Music From Satan' and all that kind of thing. I was 12 years-old at the time and I felt a little ashamed in a way. I tried to avoid that kind of thing and, at that age, I wished my dad wasn’t doing all that stuff. Then I got into The Prodigy and all that stuff and worked in a record shop when I was 15. That’s what really changed my mind.

And now here you are, with a dance music label. What's your vision for Born Electric now you've brought it back?

Yeah, I thought that it was a nice idea to bring it back. We’re trying to keep everything as natural as possible. We never went A&R for tracks.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/qYvmdnhIHLY" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>So you’re not looking for a specific sound?

Not really. We're putting out a lot of things. With most things we put out, we want it to be audible on Spotify. It’s easy to sign a couple of club weapons every month, but there are a lot of record labels doing that already.

We're going to take this interview a bit more local, now. What was your first gig in the Middle East?

It was a warm-up set for Sasha in Israel. I was really scared to go, because, three weeks beforehand. there was a suicide bomber outside of Pacha. I was really hesitant and it was one of my first gigs. But it was incredible. Since then, I’ve been to Beirut tons of times, and even for a couple of birthdays there. This year, I went to Jordan. The scene is really small there, but it was great. Dubai is kind of different to the rest.

Hold on one sec - tell us more about Sasha.

I met Lee Burridge in Bedrock one time and I kept hounding him to listen to my mixtape. I had a pocket full of cassette tapes and, actually, I used to get stopped by the security guy, who would ask me, “what are you doing with all these tapes on you?” So I gave the tape to Burridge and he foolishly gave me his phone number, because I was so keen and a bit pushy. He listened to it and, one day, he called me back and told me that he’ll give it to his agency. I didn’t know what that meant back then, but it was Sasha’s agency. The tape found its way into Sasha’s car and this is how it started. I went around with them for a little while as the little warm-up guy. I went to Romania before they sent any of the other DJs in the roster. They sent me to see what it’s like there. I couldn’t believe I was playing records for money. It didn’t feel like work. It still doesn’t, but the traveling is the tiring part.

What’s interesting you right now , globally? Is there a particular up-and-coming sound that’s grabbing you?

I think I gave up chasing sounds and trends a long time ago, because I’m just too musically confused. When I play a set now, I like to stay in the same place for a while, but then eventually go to another place. So I don’t really have a sound and I love to go from one place to the other. Which is a difficult thing because you need to be cohesive. But it’s something you learn after a while of playing.

One last (silly) question: who would you want to hangout with, dead or alive?

Mark Hollis from the 80s band Talk Talk, who passed away a few weeks ago. A real genius.

Follow James Zabiela on Soundcloud and Facebook.

Photography by Scene Noise // Ashraf Hamed

- Previous Article Getting Abyusif

- Next Article 23 Must-Watch Middle Eastern Music Documentaries