The Fringes: A Portrait of Dissonance in Ahmed Elian's Musical Debut

"Growing up into a musician’s musician is something many musicians shred for, and Elian is no exception."

"Making it to me is getting an audience that I can call an audience. I want to have a relatively strong audience. Fans, people that listen to music regularly, and more than that. Much more than that, I want the people that listen to my music to love it because they’ve listened to it in an intimate moment and connected to me through the music in a way that, I feel like only music can bring."

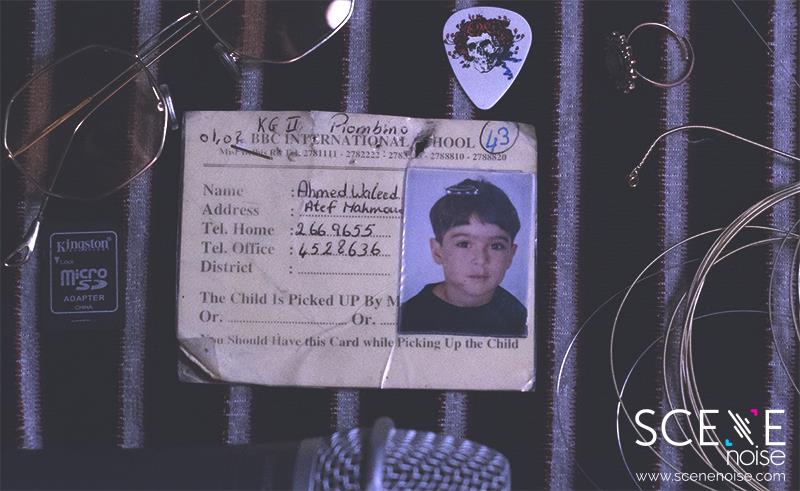

Our conversation took form amid his humble yet almost obsessive desire to stay on beat: to say the right word at the right moment, to take me up on a crescendo of metaphor and onomatopoeia, or to digress on some musical technique he’s currently playing with. Ahmed Elian, a guitarist since 7, and a producer since he found out about Garage Band, is lingering between his few month old graduation and unclear conscription status. I've met Elian as a Psychology student who made music and posted it on Soundcloud. I later attended one of his gigs with a fellow musician when they were starting out a new project: Dial-Up. Right now, he's working on a solo record: Portrait.

<iframe width="100%" height="300" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" allow="autoplay" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/162944514&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true&visual=true"></iframe>

What are you doing right now?

“I’m producing my album,” he started after a deep breath, “which I’m aiming to be a little more accessible.” I’ve known Elian for a fascination with dissonance and oddity, but he says this album promises to be something closer to what we know as “vibey” and essentially popular, but still true to what he grew to appreciate, “unlike everything else I’ve done which has been expressive of me and completely disregards accessibility.”

How did you get here?

“I’ve been raised on a lot of classic rock and progressive rock and a bit of funk and a lot of classical music. And I thought I was this whiz kid who’s into like ancient music.” As far as it goes with him, music, like all art, should be subversive. It should speak experiment to tradition and remain progressive.

“I’d always been fascinated with things like odd time signatures, odd meters.” His investment in rocking the boat came from a youthful wanking with soul, jazz and avant-garde, where “structure is literally the enemy. You try to fight structure as much as you can.” With a reference to post-modernism here and there, he realizes that his music has to still be concept-heavy, but contests that as well with the realization that legibility and relatability are also valuable to what he wants to put out there.

In that, he told me about his recent appreciation for hip-hop, which has recently grown to birth hip-pop: a genre that is now dominant in its popularity and is well above ground now. Even in Egypt, we’re starting to see the edges of artists like Abyusif in dark-lit floating venues and parties. DJs like $$$Tag$$$ have established their rapport in the music scene by playing Egyptian rap. Elian told me he grew “militant” with his music.

“I thought that rap was bullshit, and I confess that that was a very shitty part of my life because it limited my taste quite a lot,” he confessed. When Kendrick Lamar released his critically-acclaimed and widely popular as well as theoretically radical To Pimp a Butterfly, Elian decided to catch up. “And Kendrick was an incredible fucking rapper because, not only is he an amazing wordsmith, and his message is extremely powerful.” Lamar seemed to inspire in him a playful desire to stick to the dissonance he had grown to love. “This is what I’m trying to do alone. He switches beats in the middle of the song, and that’s jarring. It’s really jarring to the listener, and jarring, although 99% of the time, it’s bad, 1% of the time, it’s revolutionary, and that’s the struggle that I’m in. Where is the right amount of jarring?”

“When I started playing guitar at 7 or 8, I was into the classics: Metallica, Hotel California; just the shit that made us all get wet as kids and I really wanted to master that. After that, I started listening to more modern progressive music. Not Tool or Opeth or any of that harsh progressive music, but Plini and Sithu Aye, and I wouldn’t be surprised if anyone hasn’t heard of them because they’re fairly underground. Sithu Aye is from Scotland and is a brilliant musician. Plini is Australian, and he makes the most beautiful angelic progressive rock music with crazy time signatures.”

Growing up into a musician’s musician is something many musicians shred for, and he’s no exception. “My music will always be weird, and even if it’s off-putting to many people, it has elements a lot of musicians would appreciate, and of course that made my music completely inaccessible.”

I heard you got in touch with Plini before.

“Yeah, I had this Ask.FM account and I would ask Sithu Aye and Plini questions about production. I was using Garage Band on my MacBook at the time and the world was full of possibilities. I would ask them “how did you get the snare to sound like this?” and they would answer me, and it was amazing because you could engage with these artists which is something you can never do with Ke$ha or Bruno Mars for example.”

“Part of the Pop appeal is that they are inaccessible. They are gods, and you are the consumer and that’s going to be it. You're going to take this product and listen to it and think that they are gods and they’re above human and that’s that. Because they have a whole label working for them perfecting their music, making it sound the way it does.”

In pop, the artists are indeed hard to reach. While the art is easily consumable and accessible, it is next to impossible that mortals like us would find themselves in the presence of the likes of Kanye West or Lady Gaga. The more underground, the more accessible the artist is because they’re still not as removed or elevated. They don’t have a whole body of branding and PR, besides the production itself.

“But with these guys [Plini, Sithu Aye and other underground musicians], they’re just sitting in their bedrooms like me and millions like me in Egypt and around the world. It’s very raw and honest because it’s all coming from them.” They write their music, produce, and distribute it themselves. They are directly in charge of the art they make, as well as its marketing, and they often dwell the same streams of the internet we do. What sets them apart, in that sense, is their material art-objects, rather than their auras or the brands that surround them.

<iframe width="100%" height="300" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" allow="autoplay" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/199124492&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true&visual=true"></iframe>

What about you? You’ve talked a lot about your inspiration and how you got here. Where do you see yourself pouring that out in the album?

“I remember, I would just designate a day. I would tell my friends I’m not going out today, and I would sit in my room, not have dinner because time fucking flies when you’re producing, and I would sit and record the guitar part and then program the drums and then put the reverb. And then you would see this thing come to life and I would get very angry because it’s not a true manifestation of my artistic innards because the bitter fucking reality is: everyone, every artist or musician spends their entire life trying to get to a point where they are so technically skilled that they can truly and accurately manifest what they’ve imagined into the material world. And the sad truth is, so few get to that point. I am definitely not at that point.”

“When I started producing, I was driven by very kitschy and cliché ideas.” Elian was still on Garage band at the time. He would release his music under decadent titles like “As Deep as the Heart Goes” or “Soul Searcher.” He had lots of fun doing them. But now he’s evolved into someone more rounded and eclectic in taste.

His album, titled ‘Portrait’ is the culmination of his life-experience so far, as well as his young explorations in taste, beyond what he grew up listening to. It’s a ten-track record. He said, “I feel like I’m making something, producing something that’s kind of like a manifestation of me.” Like much of modern music, especially hip-hop, he’s fondling with samples, around “72 samples,” he explains, “so many of which are nostalgic sounds: video game sounds, Super Mario, Street Fighter,” and from film and music, like “The Nutcracker theme from the Disney movie,” as well as “classical music that inspired me [him] like Eric Satie’s Gymnopadie 1,2 and 3.”

What have you finished so far? What’s the stage you’re in right now?

“I finished 9 tracks. The first one is so accessible and funky. It’s very similar to Tom Misch’s music, featuring vocalist Lella Fadda who has a very angelic voice, very smooth, very delicate. Just glides over your ear. The second track is a complete divergence from that. It starts with a sample from a very early recording of music of a barbershop quartet which leads into a trap neo-soul-chill-lo-fi beat (with dashes) that has an electric Rhodes keyboard on top of it, and brassy elements because I’m a big fan of trumpets and trombones and sax.” I had the privilege of hearing his most vulnerable track on the album as well. He described it as “completely raw, recorded in one take, and so raw that it’s cringey, but I don’t care. That is the point. I want people to feel it was hastily recorded. And I want that vulnerability to shine through.”

“The 10th track is an 11-minute track, again straying away from that 3min 4min formula of pop that kind of aims to combine everything I’ve ever loved or have been inspired by. Films by Guillermo Del Toro, fucking readings I’ve had at AUC, music that I’ve loved, my parents, my fear of my dad’s death, what I felt like when my dog died, the love of my life, my girlfriend, fear of mortality. So many things. This is the track that’s not done yet. Honestly, that’s such a task. It’s such a daunting task because it demands so much of me, and every day I’m just adding to it a bit more and I’m trying to get that done. Sorted out.”

What are some of the struggles you’re facing right now?

“The biggest problem I’m facing right now is CPU. Literally, my computer is screaming.” He has so much going on at the same time. Recording and producing is something he described using the words “bloody” and “sweaty.” His fingers would bleed and he would find bits of skin on his guitar strings, only to find out that the sound of his mother doing the dishes bled in one of his recordings, but it’s sometimes rewarding when he hears it the following day, “and it isn’t so bad. and that’s when I know it’s working because the next day I listen to it and it still holds true. It holds its own. It’s working. Whereas before, I’d listen to something the next day or months later and I’d hate it. I’d hate my work.”

Under the current hegemony of music-streaming services, Elian, like many underground musicians, struggles to find a voice. He realizes that underground musicians lack the platform to share their music or voice their opinions on it, but recognizes the presence of new spaces like Outside and Bardo which have been pushing some new blood into these streams. Online, it’s still a pain. “Your friends aren’t enough. your friends’ shares aren’t enough. and sometimes all you want to do is scream at people, and be like: invest yourself in this, but then you realize they don’t owe you that. No one owes you that, but you have to work hard and enough and produce quality, so much that they have no choice but to engage.”

What do you want to tell this world?

“I want to tell people to give the time and attention to their artist friends: be it musician, or poet or filmmaker. Because, even though they might not be very good at their stage in life right now, even though they’re learning every day, it’s a grind. It’s a very taxing process to make art and for you to just glance over it because people just want to listen to the latest Arctic Monkeys track. It just feels like shit. It feels like you’re doing your best and it’s not enough, and everyone knows what it’s like to have a big dream, and I think it’s really important for everyone to be cognizant of that: to do their part to fulfill their friend’s dreams because support is super important and it means the world to them even if you don’t know it and, even more than support: genuineness. Be genuine with it. If you don’t like it, tell them. Tell them this is shit. But don’t do the thing where you just share mindlessly and never think about it again. Engage.”

Kairo Kid is from Elian's work in progress, Portrait.

<iframe width="100%" height="300" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" allow="autoplay" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/518636361&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true&visual=true"></iframe>

Follow him on Soundcloud and Anghami.

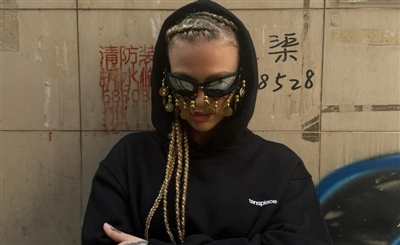

Photography by Omar Elkafrawy

This article was originally published on our sister site CairoScene.com.

- Previous Article Getting Abyusif

- Next Article 23 Must-Watch Middle Eastern Music Documentaries

Trending This Month

-

Jul 07, 2025

-

Jun 18, 2025