The Eloquent Literary Tragedy In Egyptian Shaabi Music

Shaabi music carries within its festive and celebratory tunes an abundance of deep human and existential themes, an idea that Sanabel Al-Najjar attempts to briefly delve into.

Sitting in a taxi one time, watching the flickering lights of a Cairene night, heading from Tagamo’ back to Maadi, I was exposed for the first time to Shaabi music (mahraganat). I was completely taken over by the lyrics that needed some quick deciphering (since the Egyptian dialect, when spoken in a rush, is still a challenge for me), along with the kind of melancholic Techno music and auto-tuned voices, contrasting completely with the baladi tablah and the dancey festive feel of the songs. I felt completely drawn to the songs and was happy just sitting there, feasting my ears on a genre of music completely novel to me. I was actually disappointed when the taxi driver stopped in my area and I had to step out. I asked him about the radio channel he had on, and he told me as a matter of fact “that’s my collection on USB.” I asked him for a few titles and singers. Happy with my discovery, I told a metalhead friend of mine that I loved Shaabi music. He jokingly replied to me, “fi eih ya Sanabel?”

We’re all addicted to the feel-good-I-love-him-so-much-bloody-sunshine-in-my-eyes kind of songs. The deceptive songs; the ones that do not run to your very core and scorch the hell out of it. The comfortable songs; the soothing messages. And so what is most attractive about Shaabi music is that it doesn’t abide by a false pretension of happiness and perfection, and instead musically bombards the listener with actual real problems faced by real people, the majority of which do not live so comfortably in Egypt.

After attentively listening to several Shaabi songs by different artists, I was safely able to assume that this truly deep genre of music is just as unapologetic as it is an accurate reflection of not only challenges and dilemmas faced by the less fortunate of Egypt, but simultaneously a witty exposure of universal existential themes that many of us must have headbutted against at least one time in our lives while trying to know and identify ourselves. The artistic symbolism of the human condition, the illusive idea of fate and godhood, betrayal, self-alienation, and loss as well as repent, are only some of the themes reflected in an ironically festive and all-over-the-place style of music.

The catchy tunes carry within them deep meanings that perhaps contrast and go unnoticed when played in weddings and other similarly-themed parties. I was personally shocked when I realised that the vocalists of one of the most popular mahraganat songs, Mafesh Sa7eb Yetsa7eb (with more than 24 million views on YouTube) were actually teenage boys. This made for a stark contrast with the heavy themes they sing about in the song, such as the betrayal of friends (the main theme under which fall a group of introspective topics) referenced when they says “sa7eb raagel, sa7eb faager, sa7eb beyzo2ak fi mashakel.” This translates to “a friend who is a real man (meaning is there for you or has your back), an outrageous friend, a friend who’s always getting you into trouble.” Even though this is the most integral theme of the song, which is titled accordingly, the song also reflects a defensive theme of striking back when the vocalist sings "eli bi3awarny ba3awaro" as if implying that each person should fetch for their own.

Aside from making sure to bring to light the idea that ‘we are real men’, sung repetitively in an Alexandrian accent throughout the song, the boy band also tackles the idea of sealed destinies and godhood. "Da al maktoob 3ala el gebeen 7anerdo beeh o enmashoo bi dam3 el 3een 3ala el khadein" – here the singer here is saying that whatever is destined to happen (typed on our foreheads), we will embrace with crying eyes. This astonishing (and perhaps, at a first glance, misplaced) melancholy in the song beautifully contrasts with the young age of the vocalist. This is especially the case because we find him singing about such a deep and humane aspect of feeling will-less and weak in the face of destiny and fate. "7anehrab fein men rabb el koun eli khale2na?" At this point, the vocalist poses a rhetorical question asking, ‘where will we run from the God of the universe that created us?’. Though not intentionally (or directly) blasphemous, this sentence implies the urgent need of the human being to escape the godly judgement that will inevitably take place.This ties in with another prominent concept in Shaabi songs, and that is 'repent', usually associated with running with the wrong crowd. Mahmoud El Leithy in his song Ya Donya Feeki El 3agab (How Wondrous You Are, Life), wonders about the use of money if one is not at peace. He then continues, “law kan aboya ana bi 3asayet el adab adebny makont msheit ma3 sa7eb el saw.” The vocalist here wonders why it is that his father did not beat him with a thick stick to discipline him, as that would have prevented him from going with the wrong crowd and consequently ruining his life. Going back in time and revisiting life choices (and repenting some or many of them) also characterises the honest articulation of humane concepts in Shaabi songs.Witty and artistic symbolism explode in Oka and Ortega’s Ana Kaddab (I’m A Liar). Throughout the song, the vocalist keeps singing “I’m a liar, I deceived you,” and in turn gets the choir’s reply of “no, no”. However, an almost surreal image pops out of the music when the vocalist recounts seeing an ant carrying an elephant while the car is flying and a mosquito is holding a bull. The bursting surrealism of the images in the song colliding with the choir’s denial of him admitting that he’s lying bring to our ears a strange state of mental unease while we wonder about the very reality of our everyday lives to begin with. “Bamshi wa7di bel ghaba, baftar 5arateet o dyabah,” (I roam alone in the forest, having rhinos and wolves for breakfast) is also a very dark and deeply symbolic image, perhaps referencing our agonising experience of loneliness, loss, and identity crisis. Again, this deep and unapologetic theme contrasts with the party-festive feel of this Shaabi song.What is also very striking in Shaabi music is the (absence) of the addressee, which is the person or the entity you’re addressing. In many Shaabi songs, the addressee is simply ‘el donya’ (life). In fact, in a song titled Why, Our Country?, the vocalist seems to be addressing Egypt and wondering why it is that she has been so unkind to him and favoured the cowards who betrayed her and deprived the good ones of their conscience who ended up dead. The absent addressee, or the addressee not being human, highlights the deep feeling of loss in life and the hardships that we go through as human beings in different ways.This is only the tip of the Shaabi iceberg, where more and more content keeps coming up, impressing the hell out of us, especially those among us who pay attention to the lyrics and try to view them in the authentically ironic and tragic context they are presented through. We can say nothing but ‘ta3zeem salam men gheir kalam’ to Shaabi musicians and those who always have their eyes open for the meanings these songs portray.

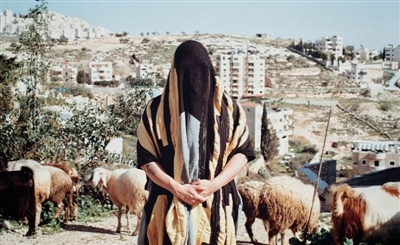

Main image published by Rolling Stone and taken by Mosa'ab Elshamy.

- Previous Article Getting Abyusif

- Next Article DGTL: Much More than a Music Festival

Trending This Month

-

Feb 20, 2026

-

Feb 09, 2026