SceneNoise x Hiya Dialogues: Badiaa Bouhrizi

Lebanese journalist and Hiya founder Shirine Saad speaks to Badiaa Bouhrizi about creating the underground anthems of the Tunisian revolution.

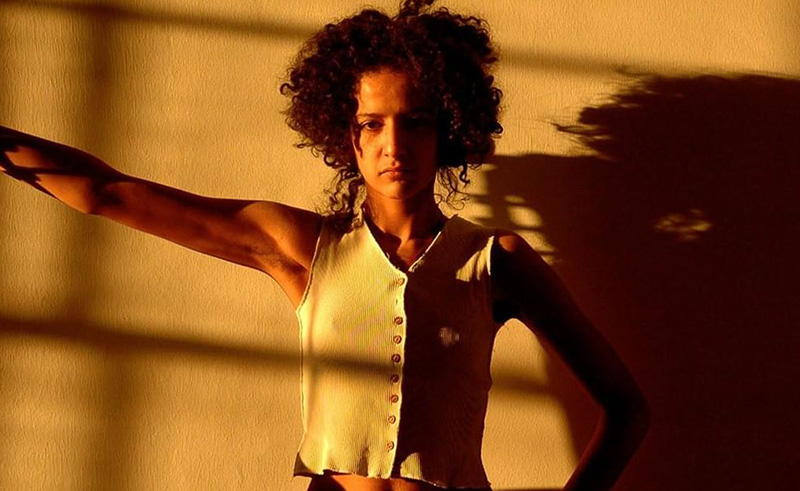

Cover image by Tayachi Bachir

Introduction by Riham Issa

Interview conducted by Shirine Saad

I first encountered Tunisian artist Badiaa Bouhrizi back in 2014 when she played at Al Azhar Park’s Geneina Theatre. I was just a 13-year-old kid accompanying my father on one of his outings with his entourage, utterly clueless about her legacy. At the time, I couldn’t fully appreciate the significance of her songs, her lore or the emotions that filled the crowd.

It wasn’t until late last year, in 2023, that I delved into her music, with a particular focus on her remarkable record ‘KahruMusiqa’ - a politically-charged musical retrospective of her early sonic experimentations when she first got her hand on music production software in the 2000s, which recently served as her first official release on streaming platforms. It was only later that I found out that she was one of the first Tunisian female electronic music producers in the regional underground scene, long before these platforms even existed.

In an era, where many artists chase fame and the superficial allure of the global spotlight, the Tunisian composer, producer and singer-songwriter doesn’t wait for industry recognition. In her words, ‘’That’s not what I started making music for.’’ Although her prolific oeuvre extends two decades back, she’s never thought of releasing her music until very recently.

Unapologetic and unfiltered, Badiaa’s music stands out as the epitome of authentic underground music, resonating with the voices of the oppressed, underrepresented and marginalized. She’s never made any compromises in the matter of free speech, actively crafting radical sonic dialogues that address political brutality and social issues around her. In Tunisia, they attach the word ‘Miltazema’ to her name, a title reserved for artists devoted to freedom of expression and social justice. In 2008, her socially-conscious songs helped fan the initial flames of protests that led to the Tunisian revolution, reverberating across the Arab uprisings across North Africa. And, despite government crackdowns on artists at the time, she fearlessly continued her work, even performing unplugged live sessions at festivals and events with police officers seated in the front rows.

Badiaa, or as her stage name goes Neysatu, managed to forge her own style, an absolute form of unrestrained improvisation rooted in the traditional North African rhythms of Malouf. She meshes together multiple cultural heritages from across the region, and influences from a myriad of genres and sounds, from Sufi, jazz and neo-soul to electronica, and Blues, into one sound that can’t be classified or labelled. It is purely and distinctly underground and most importantly hers. To this day, her ever-present courage, radiant energy and authenticity remain inspiring and influential, specifically for the young generation of emerging Arab artists. In this second episode of SceneNoise x Hiya dialogues, Shirine speaks with Badiaa about the Tunisian revolution, her musical upbringing and influences, and where she stands now as a revolutionary artist.

In this second episode of SceneNoise x Hiya dialogues, Shirine speaks with Badiaa about the Tunisian revolution, her musical upbringing and influences, and where she stands now as a revolutionary artist.

SceneNoise x Hiya Dialogues is a series conducted by Shirine Saad, highlighting radical feminist voices and influential artists from the SWANA underground scene, who are actively engaging with historical revolutionary movements to challenge the cis-heteropatriarchal and capitalist structures within the industry through their art, music and poetry.

In your music you go between two modes; from noise and rage to very meditative, contemplative and healing mode. What shaped that character you have?

There’s a backstory for that. I used to be schizophrenic. So, I am all over the place and it shows in my music. When I was in my 20s, many producers kept saying that I had to focus on one certain thing or dig in the same hole, otherwise I wouldn’t get to be ‘famous’ –which for them is the definition of success. But, I was very conscious of fame not being my road. It is not what I started making music for.

For me, music is all about communicating with something or a power that is beyond me, as a therapeutic practice. It’s something that doesn’t depend on me or revolve around me. I don’t consider myself to have any merits when it comes to making music. I think I was born with that. It didn’t come from me spending 10 hours on a piano when I was five. No, that didn’t happen at all. My approach to music is that I always compose acoustics first, then improvise, using only my internal microphone. Where were you when the revolution happened, and how did music come out of this moment for you?

Where were you when the revolution happened, and how did music come out of this moment for you?

The day when the revolution in Tunisia happened I was in London, and I went back on the second day after the strike. At the time, YouTube was censored, so you couldn’t get real info on what was happening there.

For me, the revolution really started within the artistic and cultural milieu in January 2008, and it went on for three years until that way of anger reached the world. At some point, I was performing at a beachside festival, and there were two cars of police secret services on either side of me facing the crowd. It was really intimidating. I have recordings of my voice, and it was really trembling at the beginning. Nothing happened at that very moment, I continued the show till the end, but I couldn’t play in Tunisia afterwards. Gigs were cancelled all the time. Concerts were forbidden, not in an upfront way, but rather you couldn’t even organise the smallest event in Tunisia without authorisation, at least from the nearest police station to your location.

I know that people kept passing my music through USBs. That’s how my music circulated, because, of course, I couldn’t put these songs on the internet with my name.

One of the key moments for me was when I was performing at that festival by the beach, with the police cars on both sides of me. There were so many people, and I felt an exchange of power between me and the crowd. I realised I gave them immunity through my music and made them realise their power as a collective. They also protected me in return by being so many. The police couldn’t take me then because there were so many young people, and they were really, really angry. I know that if something were to happen to me that night, they would have burned the police cars. So, I love that symbiotic kind of relationship and that way of challenging the limits of fear. This is what kept so many artists there going.

What were these songs about, that you were singing and the people were circulating on USB drives?

They were all protest songs, all related to social issues. In 2008, the first song I did was talking about the kid that they killed two months before in June. His name was Hafnewy Maghzawy. I made a song about him and in the middle of it, I was talking about the royal family. and I even named the wife of the president and their palaces and everything.

Back then, most of the leftists in the artistic sphere, especially in theatre, would talk in riddles. I was part of this generation, but I was like, “No, there should be a confrontation in our art,” like say, “This is not democracy, this royal family is corrupt.” I believe that is also what made up the Tunisian underground scene - politically explicit content. I know you and your brother had several issues with the government. Were you ever scared? And, how did you deal with that kind of censorship and fear?

I know you and your brother had several issues with the government. Were you ever scared? And, how did you deal with that kind of censorship and fear?

The fear? I have never had fear for myself really. When I was performing with cops in front of me with their guns, a small inch of freedom within me was kind of unlocked, and I felt absolutely fearless. But, I also remember having nights where I kept throwing up out of fear for my family. Because my brother was also in prison and I was super scared of what they could do to him.

He was in prison partially because he was making music as a rapper, right? Can you tell us more about his work and what he was rapping about?

Yeah, he was actually far more fearless than me because he would start his concert by saying ‘I know there are some cops here; if you are cool show yourselves, and if you are not, you know we won’t change anything’ And, at the end of each of his concerts, they would arrest him and rough him up.

His music was socially-conscious, talking about life as Tunisians and how they grow up not feeling manly because they don’t have the freedom to dream of starting a family just because they don’t have connections within the government.

You’ve always had such strong connections with other artists and mentors, did so many collaborations throughout the trajectory of your career, and still continue to thrive on connections with your community. Despite the lack of trust and the lack of safety, I feel that you were always able to find your people. How do you do that?

I think it is almost mystical how you find your people. It is like everyone appears transparent-like, but in your tribe appears full of colour and vibrant. Those connections I’ve made never happened on conversational or intellectual grounds, it generally happened spontaneously over a drink or something. Sometimes, they happened through meeting different musicians from what we call the underground music scene. But, I have no explanation for how these kinds of connections and collaborations happened to me. It feels like a divine plan or something that was beyond me and them. We were supposed to meet and like each other musically. Zeid Hamdan, for instance, is one of my favourite encounters. He is like the godfather of Arabic electronic music in the underground scene.

Sometimes, they happened through meeting different musicians from what we call the underground music scene. But, I have no explanation for how these kinds of connections and collaborations happened to me. It feels like a divine plan or something that was beyond me and them. We were supposed to meet and like each other musically. Zeid Hamdan, for instance, is one of my favourite encounters. He is like the godfather of Arabic electronic music in the underground scene.

For me, being an underground artist is making music in an unapologetic way, not caring about the industry’s expectations of what an artist should do in order to succeed. If you succeed and reach fame, you are mainstream, you’re not underground. Like, if you call yourself a rock or punk underground band and make a love song saying “He cheated on me” or something, that is not really punk though. We cannot use a subversive form with content that is politically correct. I hate that.

You have a very diverse musical upbringing. You grew up listening to classical music like Umm Kulthum and Abdel Halem, but were you also listening to political songs?

No, I wasn’t listening to political music at all. I was simply into music back then just purely for music, not for political reasons at all. I didn’t even like Sheikh Imam early on, I found it too harsh at that time. It was later when I had that kind of musicology to realise that his compositions are amazing. He is obviously a genius composer.

How did studying musicology influence you?

It taught me that music is not something that you learn at school. It is an art or science of the ears, you can develop your ear, and you can fail at naming what you’re hearing, but if you can do it, it doesn’t matter because that theoretical knowledge comes later with consistency. Like, a table won’t change because you are not calling it a table. If you can use it, you can use it, you know? Music is like that. iIf you can make notes, you can make music, it doesn’t matter what you call it. You can call the scales whatever you want.

For me, studying musicology was like an eye-opening moment, because it made me understand one thing, that you can not learn music at any school. It entirely took out a complex that I had around academic music or people who can read parts or notes. Before studying musicology, you were in a choir at a very young age, and then went through a rock phase, before going to jazz for a while. Can you walk me through all of these stages you went through?

Before studying musicology, you were in a choir at a very young age, and then went through a rock phase, before going to jazz for a while. Can you walk me through all of these stages you went through?

When I was really young, I used to be in a local choir as one of the soloists, and we sang a lot of Fairuz’s songs. Later on, there were songs by many other artists like Umm Kulthum, who I didn’t like as a kid. I liked her very late. But, I remember that one moment when I was 10, there was a song by Bob Marley called ‘Could You Be Loved’ playing on the radio, and I started going around the house spinning with my arms out because I’d just first discovered that music.

Then, I started discovering more about music, and I was very enchanted by harmony actually, and that kind of stuff, it was just so joyful you know. Maybe, because I’ve had enough of that minor scale of Arabic music so it was like, ahh, major - and not major like Beethoven-scary-major, but like a joyful major.

And, then around 14 or 15, I started discovering rock like Pink Floyd, Radiohead, Led Zeppelin and a lot of old bands. It was like a musical revelation that came during my teenage years, and I even went on and joined a rock band for two years with my friends. At the time, I didn’t realise there was a scene for that. But, when I joined that scene, I was like on a cloud, for at least the first year of it.

Later on, I started being into jazz and classical music of mwashahat which was really interesting. The people and musicians in that area were a lot like me, which wasn’t what I expected at all. They were in it for the form and the aesthetics, and they wanted to learn the real secret and the ground rules of that music.

I wanted to be a jazz singer at some point, but when I went to many jazz concerts, I didn’t like the audience. So I was like, I don’t want to sing for those. I am sorry. It was the audience that really put me off of it.

Revolutionary music. This is a topic that you have been exploring since the beginning of your practice as an activist and an artist. From your perspective, what does it mean to be a revolutionary musician and what does it mean to make revolutionary music now?

It is kind of an ocean to dive in. But, to start, I think it is very important for any artist not to feel like they have to be neutral because now everyone is saying, “Just do your art, what are you thinking integrating topics of political interests?”

For me, as an artist and a human being, my practice is linked to my expression, my emotions, and my reactions to what is happening around me all the time. You know, some people cry at home, I resolve to cry and make a song. It is organic, I’m not putting a special effort into becoming an activist. It comes naturally. I think it should also come naturally to any artist if they are true to themselves. When you are an artist, you have to be empathetic, otherwise you won’t feel the emotions of other people. I think it is hypocritical for any artist now, being known or really in the underground scene, to ignore what is happening in Palestine or Sudan, or choose not to expose the hypocrisy of the Western world.

I think it should also come naturally to any artist if they are true to themselves. When you are an artist, you have to be empathetic, otherwise you won’t feel the emotions of other people. I think it is hypocritical for any artist now, being known or really in the underground scene, to ignore what is happening in Palestine or Sudan, or choose not to expose the hypocrisy of the Western world.

That’s revolutionary music, just being yourself as an artist and not becoming a slave to capitalism or imperialism, or having those principles of competition. And, to address that question of Palestine or talk about any injustices that are around at even a small scale, that’s really the core of your practice as an artist.

For you, this revolutionary consciousness began from an experience of oppression, of an experience of I can’t say what I want to say in Tunisia?

When I first started making music, I was actually influenced by 70s rock music. It was more authentic in terms of words, it was more for now. It wasn’t only about love stories and conceptual or poetic things that would take us out of reality - it was into reality. Transposing that to my Arabic-speaking environment was how I first wrote my first songs, which came out naturally talking about the social injustice that was around me. The first movement that was doing that in Tunisia at the time was actually hip-hop. The rap scene was too in tune and talked about what was really happening back then and that’s what really gave me the first insight into the world I was living in.

It wasn’t like there was a choice though. I don’t know how I can explain it enough, I don’t remember there was a moment when I thought I’d be writing about this - about what happened to this boy who was killed in Tunisia because he went out in a protest. I was singing with my guitar and then his name came and I kept going and I would rewrite the words to make them good. But, like I said, it is all about having a very organic approach, if you are true to yourself and empathetic and not imprisoned by fear.

Being at the age of 17, when I first started doing this and writing songs, I was naturally rebellious. At that time, there was this revolutionary movement in the artistic and cultural sphere. I realised I wasn’t the only one who was part of it, so many artists were moved by the same thing. It was the question of, ‘What are the limits?’, ‘What is fear?’, ‘Is it real?’, you know. Like, ‘Where is the policeman really?’, ‘Is it inside or outside of me and can I just take it out?’

Our explicit writing about politics and naming names and so on was a kind of attempt to explore this, and undermine that organised security thing that was there to prevent us from being free. Tell us about your initial experiences of rebelling, and personally, what were you rebelling against, and what sort of limitations do you feel you had on your movement and your life?

Tell us about your initial experiences of rebelling, and personally, what were you rebelling against, and what sort of limitations do you feel you had on your movement and your life?

The first act of rebellion really wasn’t political but more against my position as a woman. Because, girls can be touched in the metro and they shouldn’t be talking about it or be aggressive, and they are not allowed to smoke in the streets. I remember being really angry and in that frame of mind of ‘No’, and I started smoking just out of spite.

I think those little things are what shaped my current mindset, and were the first things I rebelled against. Through my rebellious actions, I started to create that small window of freedom for me that started growing bigger and bigger over time. And, when you are intersectional, you realise that you are the oppressed in a very oppressed society. Men may be more free than you but they are not actually that free, and once you get to the level of freedom they have, you don’t care. You start to impose your own ideology and you do what you want and you realise it was also in your head most of the time.

Musically, what did this sound like that rage and that anger you had?

I was in a rock band so it sounded really harsh. And, we used to be really provocative. I remember one gig where there were police, and they kept trying to get me off stage, just because I kept putting the mic stand between my legs and playing sexually about it. My intentions weren’t seductive, it was really provocative. I was wearing a very short skirt and black, very rock-like clothes, and playing with the limits. And, I knew very much that I was addressing women with my actions, not men. They wanted to stop the show but they didn’t.

It’s so interesting how music has the power to provoke so much rage from legal establishments.

You mean how they feel threatened by it.

Yeah!

It’s amazing! I think they realised how music and arts are very important in shaping young minds. It happened to me, when I started really understanding the lyrics of the music I grew up listening to, it shaped my mindset at the time. I realised then that political stances and freedom can be a frontal request in music.

I think what they didn’t understand was that the more you react the more it amplifies when it concerns youngsters. I think the underground scene that I lived in gave the revolutionary adults a reason to start the revolution. I mean the ones who were between 20 and 30 in the underground scene were putting out self-composed music in Arabic criticising what was happening, which started drawing the police’s eyes and started the revolution. So, of course, they tried to shut it down - propaganda needs to shut down the dissident voices because they have the power to shape and influence many more people.

So, you have had influences from punk rock, Bob Marley’s reggae, and of course North Africa, and Arabic music. How did all of these influences come to you, and how did you first start to shape a revolutionary sound that was rooted in the place that you were in?

I remember the exact moment of revelation about that. It’s when you realise that your first political choice or life choice is also choosing the culture that you want to maintain or preserve. I started to realize that the foundations and principles my country is built on came from a previous colonialization, and there is a subtle colonisation still going on, culturally specifically. They even taught us that at school we are called the third world.

Once I realised that my hometown, Tunisia, which has ruins that trace a history of 7,000 years of civilisation, is called a third-world country. I decided to talk about that. I wanted to have a connection and to sing to my people and talk to them in my language. Even though I wrote songs in English and French, I never released them. And, it wasn’t only me who was doing that at the time, there was this awakening or renaissance movement across the Arab world. And, maybe it was linked to our generation who didn’t live under any type of colonisation.

Anyway, the choice was clear to write in Arabic. In terms of lyrics, I wanted to talk to my people and pass my emotions in my mother tongue, which all came rather organically. And, in terms of music, I left that more freely. In terms of arrangements, I don’t think that I am using only the heritage of my country, but I consider the heritage of all humanity to be mine. When you’ve also studied musicology, which addresses that there would be no evolution in music, and we would be still a monotonous thing if there were not these movements and influences from other cultures. You know, how people have those little musical sentences and then they play it in their own way and afterwards it becomes this new traditional music of that country, but at the very beginning it was coming from something else.

That being said, I consider all human musical heritage as mine. And, I realize that my voice is my identity whether I like it or not. So, it is a mix of choices and letting go of like trying to cater or to fit in an established frame.

You have been exploring through your work the mystical ecstatic tradition of Sufi music. So, tell me a little more about the voice and the drum in these traditions you’ve been exploring.

The foundations of the ‘trance movement ’ are very instinctive in organic cultures. I was very interested in exploring that. In our region, at any family gathering, the people would start chanting anthems and there’d be no other instruments but percussion and vocals. And, even when these songs don’t have any religious or spiritual purposes, there was a general element of trance to it, you know. I realised that it was all about the drums and vocals.

The vocal instrument is the one instrument that actually has all the specificities of all other instruments, which means it has strength, the chords, the air and the percussive element.

In Sufi music, the element of trance is activated by certain types of rhythms, which are called the ternary rhythms. These are the rhythms that get you in a trance and it can be controlled if you control the tempo. So, they liberate your consciousness from being in the present and enable you to actually communicate with a divine force beyond you or a divine part within yourself. You discover we are capable of everything, there are no limitations actually.

In Tunisia, we have many methods of Sufi movements. A big majority of them would be Muslim Sufism. In those, there is a little bit of trance, which is actually a state you shouldn’t enjoy. It is rather a state that is needed for some people when they have problems that they need to be freed from. Then, you have the ‘Stambeli’ movement, which really talked to me. Because, first it is very linked directly to Africa; it is a musical movement with a clear African identity. It is a spiritual movement that originated from the black community in Tunisia and expanded afterwards. Secondly, the trance element within this movement is very controlled. It’s actually good to get into that state and doesn’t make you lose control.

What I really love about it is that its rhythms have a complexity that when you dance to it, it feels as if you’re dancing in the sea. The tempo has a kind of polymetry to it - it kind of expands a little. And, you have songs that are really linked to different elements, like stuff that you’d find in Cuba for instance, the music of Orisha. The rhythm is very earthly and organic and doesn’t get you stuck in a fixed state of trance but rather takes you through a whole spectrum of movement and cadence. It takes you through small joyful jumps of trance. So, you lose control a little but with finesse.

What you are describing - that pattern of going from one thing to another with no strict structure/form or frame - is dissonance. Most non-Western artists don’t like the word ‘dissonance’, because it means out of tune. How do you feel about this word and how do you think we should reclaim it?

I think that we should reclaim it. Because through dissonance, we express dissent against the West. I mean, all of the old and even modern music, from Blues, jazz to pop, funk, house and techno now, all came because some black musicians, like from the 19th century, started playing dissonant music. For instance, the foundation of jazz was actually expressing dissidence by dissonance. White musicians would steal the music that was being played all around America, and they would play it. So, that led jazz musicians, for example, to break more rules until they got to free jazz - which if you didn’t have it in you, you couldn’t make it, or replicate it. It is not possible.

So, that’s what the West is trying to do. I think the word ‘dissonance’, we have to own it, it is like reclaiming what is kind of pejorative to being what it is, and the fact that aesthetics are not defined by one culture to the whole world and that ethnocentricity era is gone.

If you think about the sounds of war, the ecological reality of living under the bombs and not having homes - that’s created by Western imperialism. Musically, how can we sort of take that noise and reclaim it but also transform it into something that can be healing, dissident and cleansing?

I think the first step is to recognise it even musically and to express it as it is. I have a lot of respect for the work of Kamilya Jubran because I think she is expressing the dissonance and disruption of the reawakening of imperialism that’s currently happening across the Arab region. I think it is a very hard exercise. You have to be honest and get outside the spectrum of the normal feelings and emotions that we are told to express as musicians. To have that audacity and the technical luggage as well as the emotional transparency to be able to express this is a very hard exercise and not everyone can understand or get.

But, I believe that once you get to express yourself, then you can get to the healing part. It’s like Blues. In Blues, at the beginning of it, it is an expression reminding you of that moment when you were really down at rock bottom, and at the end of the piece, you feel like that feeling went away with the music. So, I think in order to get to the healing point, we have to have the courage first to express in a way that is not normal or doesn’t fit within the boxes of what would work in the music industry. Again, it’s hard.

You’ve been making music now for two decades. Today, Where do you stand as a revolutionary musician, and how have your thoughts and ideas about music changed with all of these incredible events you’ve experienced?

I feel the change but I have no control over it. It’s either what’s happening around me or what’s happening within me. For a long time, I wouldn’t know how to take someone criticising my music. But, now I am appreciating my music more, and I’m much more at ease with my weird ways. I am more comfortable with myself when I am programming my compositions. I feel like this evolution or change is symbolised in my song ‘For Longing’, that song marks something - a change in composition and arrangement. And, I love that I am going that way now, playing on those small harmony elements and slightly changing just one note or one chord and letting it resonate. It aligns with my way of thinking when I was 17, which was making music that was not obviously clear.

I think the revolution and all of that I have lived through and the people I have met, are all a huge part of that change. It made me realise that my tribe has no nationality and that we are much more than what we tend to think. There are so many entities trying to impose how much should be done, so you have to have some kind of resistance to that.

You can manipulate these elements they are imposing to make something that’s you and beautiful, and be the soldier of love.

- Previous Article Five Albums That Tell the Story of Moroccan Rap

- Next Article Trap Meets Shaabi: Is It Overused?

Trending This Month

-

Jun 04, 2025

-

Jun 05, 2025