Kafrawy: The Photographer Keeping a Lens on Cairo’s Music Subcultures

Inside Cairo’s underground parties, photographer Kafrawy is determined to remember everything through his work.

Walking amidst Cairo’s perpetual soundscape, keeping an ear and eye out for the city’s rising voices is music and documentary photographer Kafrawy. As a rising artist himself, Kafrawy brings an ethnographic approach to his work, focusing on subjects that are as young and experimental as he is. While his images document up-and-coming musicians, Kafrawy himself participates on sets and at parties - which often give him the best angle with which to take that one, all-encompassing shot.

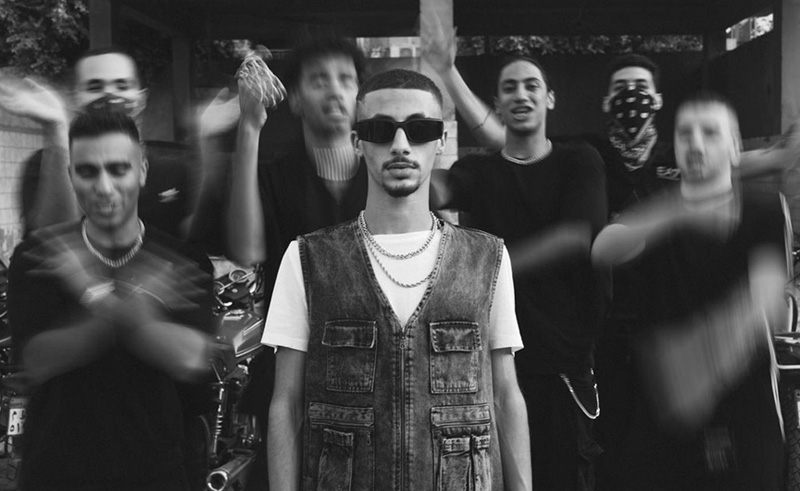

Having practised photography as a hobby between 2013 and 2017, Kafrawy would use his daily commute on Uber Scooter as an opportunity to document the streets of Cairo. In doing so he captures what he calls ‘Cairo surrealism’; a way to look beyond the bigger picture in order to see passersby’s quirky daily behaviour. Later on, he began taking pictures of parties out of a desire to capture Cairo’s quickly emerging music scene. He thinks of the first Cairo Jazz Club gig by Palestinian music label and collective BLTNM, and the rise of Egyptian trap artists Wegz and Marwan Pablo, as a personal launching point. After being a consistent presence behind the scenes with regional and local artists, Kafrawy’s latest work is now on display at the ‘Impressions’ exhibition, which is running until March 3rd as part of Cairo Photo Week and with the support of The French Institute in Egypt. His photo series features the rebellious Maadi-based crew, Maadi Town Mafia, in their neighbourhood; with black and white photos and an homage to ‘A Great Day in Harlem’ (1958), the rappers occupy gallery walls with their daring persona, as interpreted by Kafrawy.

After being a consistent presence behind the scenes with regional and local artists, Kafrawy’s latest work is now on display at the ‘Impressions’ exhibition, which is running until March 3rd as part of Cairo Photo Week and with the support of The French Institute in Egypt. His photo series features the rebellious Maadi-based crew, Maadi Town Mafia, in their neighbourhood; with black and white photos and an homage to ‘A Great Day in Harlem’ (1958), the rappers occupy gallery walls with their daring persona, as interpreted by Kafrawy.

We caught up with Kafrawy following the opening of ‘Impressions’ over a Zoom call. With a bright yellow wall that he disapproves of as his background, we talked about his urge to document, and the need to remember and remind people through his work.

The group exhibition is running till March 3rd at the French Institute in Mounira. Having captured rising and established musicians, parties, and underground spaces, did you always intend to document them?

Having captured rising and established musicians, parties, and underground spaces, did you always intend to document them?

Yes. Initially, it was smaller in my head. I've always been fascinated by music and hip-hop in Egypt so I was trying to put that into my images and keep them for myself, then I started posting on Instagram when I started feeling comfortable with my photography as a skill. But the purpose was always to remember and to remind.

Does shooting or having your camera feel like a 'way in' for example to some spaces?

How it started was that I would kind of hide behind the camera, and enter the space with it as my friend, my tool or my mask. At certain times, it became a barrier, so then I would stop taking pictures. Of course on some level, it has afforded me access to spaces and got me invited to really interesting music-related spaces, but it only happened when my effort and love for what I'm doing was acknowledged by, basically, my subjects. The people I was capturing started noticing my love for what was created out of their spaces. How did your project with Maadi Town Mafia start?

How did your project with Maadi Town Mafia start?

I noticed them and was really taken by their work when 'Agana' came out. Then I got a call from their producer to shoot BTS for their music video, ‘Logan’. From there on I started telling them to let me know when something was happening. Then I decided I want to create something about them, something that's more intentional. Less fly on the wall, and more ‘let’s make an image’. So I started sending them references. I wanted to create a ‘day in Maadi’ with them. It was inspired by ‘A Great Day in Harlem’ (1958). This picture was replicated more than once, so we met in McDonald's at Street 9 next to the Metro and did it.

Rappers in general and Maadi Town Mafia specifically have a very strong ‘persona’, is that part of your interest in documenting their journeys?

It’s very easy to place artists in the brand they choose to put out, they’re very talented and they’re performing an artistic act, and it’s a very powerful one. There is masculinity to it and there is aggression and bravado and violence. I’m quieter, but they're peaceful and nice on set. We all do enjoy a little ‘ha’ataa’ weshak’ (in reference to FL EX’s ‘Logan’ lyrics). When I first met them we loved a lot of the same things, hated the same things, and shared the same rage.  How do you approach your relationships with artists and being part of their stories?

How do you approach your relationships with artists and being part of their stories?

When it clicks, it clicks. It always comes naturally with the people I work with. I've been lucky to have been told that I’m comfortable to have around and that my presence isn't intrusive. I'm very aware of having people be comfortable on camera because it shows when they’re not. The most important part of my work is that I’m genuinely curious about the people I’m shooting and that we’re all comfortable throughout the process. You mostly document underground gigs, why is that a particular interest?

My interest in smaller gigs stems from the fact that it feels safe and comfortable to be in and to shoot intimately, and it feels important to contribute culturally to something. My presence at the party is important to it as both a party-goer and a photographer. It’s also partly about the music I enjoy, which is somewhere between weird experimental club music, grime hip-hop, and drill. Anyone can shoot up-scale parties, and it feels like there isn’t really a story there.  You’re very vocal about your responsibility as a photographer at parties, or spaces that can often lead to violence, can you share a bit about that?

You’re very vocal about your responsibility as a photographer at parties, or spaces that can often lead to violence, can you share a bit about that?

I try to put myself in the position of someone who’s part of an economy. Those parties are political, economic, and social spaces with a lot of structure. When those spaces become home to violence everyone becomes complicit.

I want to take pictures I’m proud of, and I want to signal that if I capture a space then I approve of this space and its politics. If we’re all there then we're all responsible for it, and I don’t want my images to be tainted or used to market for a violent space, I wanted to reject that.

- Previous Article test list 1 noise 2024-03-13

- Next Article ALBUM SPOTLIGHT: HUSAYN - ‘SWITCH’

Trending This Month

-

Jan 29, 2026