Diving Into Spotify’s Stream On Event and the Future of Audio

SceneNoise was invited to attend the second iteration of Spotify’s Stream On in LA to learn about the company’s roadmap, royalty payouts, artist development, and the Fan-First programme.

Founded in 2006 by Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, Spotify - the Swedish audio streaming and media service provider - has become the world’s biggest music streaming platform with over 500 million monthly active users, and 200 million subscribers in 184 markets around the world. Just last week in Los Angeles, California, Spotify put on its second Stream On event, where it announced metric milestones, new features and tools, live demos, a walk through its roadmap, and key findings from its annual Loud&Clear report.

It was the first physical iteration of the event, where it hosted hundreds of creators in the Los Angeles Arts District, giving a live platform to the company’s leaders alongside a curated list of industry icons, and creators. Speakers and testimonials came from artists including The Jonas Brothers to podcast phenomena Alex Cooper and Emma Chamberlain, following several speeches by Spotify’s CEO, Daniel Ek, Co-Presidents Gustav Söderström (CTO) and Alex Norström (Chief Business Officer), and the Global Head of Editorial Sulinna Ong, among other directorial voices from across the company.

“Today, there are more than ten million creators on Spotify with over half a billion listeners across 184 countries and markets. Think about the massive potential that represents for creators,” Daniel Ek said in his keynote speech. “No matter where you are on your own creative journey within music, podcasts or audiobooks. The potential to reach half a billion people. And that reach is about to become more powerful with what we’ve introduced today.”

“Today, there are more than ten million creators on Spotify with over half a billion listeners across 184 countries and markets. Think about the massive potential that represents for creators,” Daniel Ek said in his keynote speech. “No matter where you are on your own creative journey within music, podcasts or audiobooks. The potential to reach half a billion people. And that reach is about to become more powerful with what we’ve introduced today.”

Following the Stream On presentation, Spotify “opened the doors of its campus in Los Angeles’ Arts District to creators for its Play On event to demo products, workshop with top industry creators and get expert tips on how best to use Spotify from the people who helped develop the tools at the company.” The evening culminated with an all-female artist showcase to celebrate International Women’s Day with performances by Léon, and later, Rita Ora, followed by the legendary Gwen Stefani.

The event was impressive to say the least, to be a fly among the wall of the 200 or so people at the precipice of future tech at the intersection of media, machine learning and music. In many ways it was clear that Spotify is trying to drive its own narrative, particularly within the context of artist-centricity, copyrights and payouts.

The event was impressive to say the least, to be a fly among the wall of the 200 or so people at the precipice of future tech at the intersection of media, machine learning and music. In many ways it was clear that Spotify is trying to drive its own narrative, particularly within the context of artist-centricity, copyrights and payouts.

Over the years, Spotify, Apple Music, and other streaming platforms have been criticised for royalty breakdowns that leave the artist with only $0.013 to $0.003 per stream. And while Spotify’s payouts are on the lower end of the scale, some attest to the better and more intuitive features for artists that the platform offers, along with the merchandise integrations, and data points captured.

But is that enough? And what is Spotify’s actual ecosystem?

To answer this more transparently, Spotify recently published and made public its Loud&Clear report, offering key takeaways that are difficult to ignore when looking at how it has impacted the music industry’s economics at large. Here are some insights:

“All-time Spotify payouts to music rights holders are approaching $40 billion. Every year, Spotify pays out money in streaming royalties, resulting in record revenues and growth for rights holders on behalf of artists and songwriters. These right holders include record labels, publishers, independent distributors, performance rights organisations, and collecting societies (Spotify does not pay artists or songwriters directly).”

Meanwhile, “Spotify pays out nearly 70% of every dollar it generates from music back into the industry,” and it does so through “two sources: subscription fees from Premium listeners and fees from advertisers on music on the Free tier.”

According to Loud&Clear, the number of artists generating $1 million or more, as well as those generating over $10,000, has more than doubled over the past five years. And while Spotify has not yet met its motto of “giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art,” the royalties unlocked for them has been growing. “In 2022, 57,000 artists generated $10,000+ (up from 23,400 in 2017). And 1,060 artists generated $1 million+ (up from 460 in 2017).”

According to Loud&Clear, the number of artists generating $1 million or more, as well as those generating over $10,000, has more than doubled over the past five years. And while Spotify has not yet met its motto of “giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art,” the royalties unlocked for them has been growing. “In 2022, 57,000 artists generated $10,000+ (up from 23,400 in 2017). And 1,060 artists generated $1 million+ (up from 460 in 2017).”

Moreover, “for the first year ever, 10,100 artists generated at least $100,000 on Spotify alone. That’s up from 4,300 artists five years ago, and due to the lowered barriers to entry, these artists hail from more than 100 different countries around the world.”

“Spotify announced there are nearly 200,000 professional or professionally aspiring recording acts globally on Spotify, and they generated 95% of the total royalties in 2022, many of whom used independent distributors like DistroKid, TuneCore, CD Baby, or others to self-release.” To give more context, “Based on each platform’s average pay per stream rate, Apple Music pays double” what Spotify pays per stream, according to DI++o music blog’s recent research. “This is mainly because Spotify has significantly more users than Apple Music, which means the rate per stream is lower due to more royalty shares.”

“Spotify announced there are nearly 200,000 professional or professionally aspiring recording acts globally on Spotify, and they generated 95% of the total royalties in 2022, many of whom used independent distributors like DistroKid, TuneCore, CD Baby, or others to self-release.” To give more context, “Based on each platform’s average pay per stream rate, Apple Music pays double” what Spotify pays per stream, according to DI++o music blog’s recent research. “This is mainly because Spotify has significantly more users than Apple Music, which means the rate per stream is lower due to more royalty shares.”

When using the Apple Music Royalty Calculator, 1,000 streams will get you about ten bucks, or 100,000 will generate nearly $1,000 or EGP 30,000.

So what, then is the problem? Why does music streaming at large continue to be a polarising topic within the music industry? And where did this debate begin?

The problem often cited is that Spotify and other streaming services do not pay out enough royalties to musicians. Speaking to this point, at this year’s Stream On, Spotify confirmed paying back close to 70% of every dollar generated from music as royalties to rights holders who represent artists and songwriters. When digging into Spotify’s financial reports, the company's income statement reported over $11b in revenue, with $8.8b in cost of revenue, which consists predominantly of royalty and distribution costs related to content streaming.

There is, of course the algorithm auto-play debate, about what it means for a company to drive taste in the way Spotify is through its autoplay functions, and what that might mean for the future. Particularly if these autoplay functions end up driving music made by AI versus humans, and the hyper-capitalistic possibilities that presents.

In many ways, this is what it means to be a disruptive technology. To change the user experience but also be a catalyst for a paradigm shift in thought and contemporary discourse. According to the Loud&Clear report, “Spotify and streaming are driving a healthier, more diverse music industry than ever before. As a point of comparison, a radio station typically plays a rotation of the Top 40 songs, while one the largest record stores in the heyday of physical record sales, carried the music of a few thousand artists.” And in this finite airtime and shelf space, everyone who had access to these limited slots in a certain geography was sharing the same cultural moment, where choice was entirely pre-selected, and media was almost exclusively deployed with a top-down approach, creating ‘monocultures.’

In many ways, this is what it means to be a disruptive technology. To change the user experience but also be a catalyst for a paradigm shift in thought and contemporary discourse. According to the Loud&Clear report, “Spotify and streaming are driving a healthier, more diverse music industry than ever before. As a point of comparison, a radio station typically plays a rotation of the Top 40 songs, while one the largest record stores in the heyday of physical record sales, carried the music of a few thousand artists.” And in this finite airtime and shelf space, everyone who had access to these limited slots in a certain geography was sharing the same cultural moment, where choice was entirely pre-selected, and media was almost exclusively deployed with a top-down approach, creating ‘monocultures.’

Now, we live in a much more fragmented ecosystem of choice that breaks down cultural moments and musical styles into granular tags, and micro-subcultures that fade before they even arise. In this case, fragmentation arrives to promote experimentation and technological divisiveness to avoid homogeneous categorization that places everyone outside of the US and Europe in the “world music” or “other” box at record stores.

Meanwhile, prior to streaming services, the music industry was (and still is) notorious for its decades long exploitation of artists as a result of bad label deals that left artists owning little to nothing of the music they created and performed.

Then came the pirates.

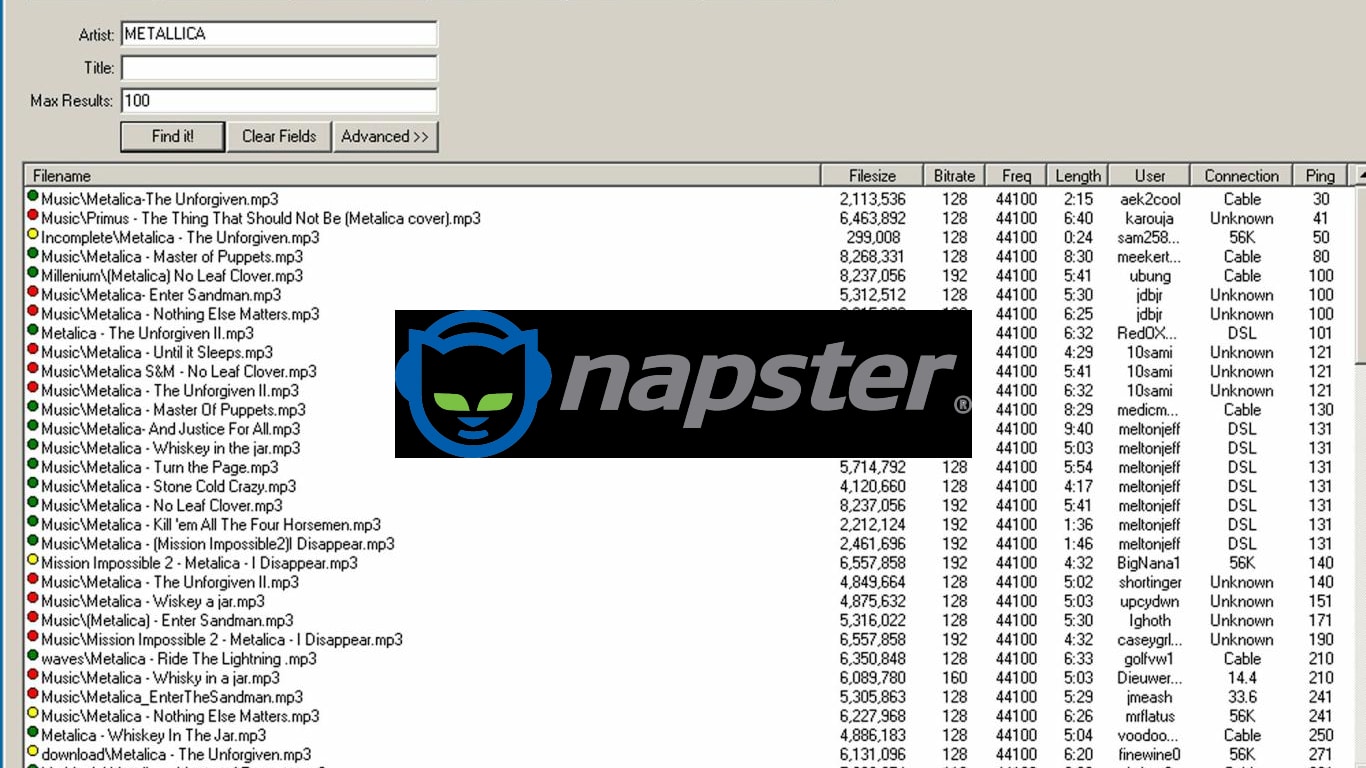

In 1999, Napster launched its free peer-to-peer file sharing service that forever altered the course of the industry by disrupting how we consume and share music. Napster was arguably a hyper-corrective technology with an almost anti-capitalistic approach, much in line with the ethos of peer-to-peer file sharing, and even though it was hugely popular, it immediately ignited many ethical and legal debates directed at the copyright, permissions and ownership of works by musicians. Despite this, nearly 80 million users downloaded Napster, while willingly and blatantly disregarding royalty ethics to freely download the music they loved most, and nothing was the same again.

Napster was eventually shut down in 2001 due to the lawsuit by the Recording Industry Association of America, the trade group for the US music industry, which confirmed that the company was facilitating the illegal transfer of copyrighted music. But the tides had already shifted, and a new MP3 course was drawn, and in 2003 Apple launched the iTunes Store and the iPod. Soon after in 2005, Pandora arrived to combine iTunes’s streamlined interface with related musical characteristics, to create an online service, which recommended new music based on a user’s listening history, allowing users to bookmark artists and discover new acts.

Napster was eventually shut down in 2001 due to the lawsuit by the Recording Industry Association of America, the trade group for the US music industry, which confirmed that the company was facilitating the illegal transfer of copyrighted music. But the tides had already shifted, and a new MP3 course was drawn, and in 2003 Apple launched the iTunes Store and the iPod. Soon after in 2005, Pandora arrived to combine iTunes’s streamlined interface with related musical characteristics, to create an online service, which recommended new music based on a user’s listening history, allowing users to bookmark artists and discover new acts.

When Spotify’s CEO Daniel Ek first co-founded Spotify in 2008, he told the New Yorker, “It came back to me constantly that Napster was such an amazing consumer experience, and I wanted to see if it could be a viable business.” And now, after announcing almost $40b in royalty payouts, it might be safe to say that Ek has succeeded in not only finding a viable business model but one that continues to scale exponentially.

Doubling down on helping artist discovery and Fan-First programs

An often overlooked perspective in the Spotify experience is that of the fan - instead the company has often been positioned as an artistic-centric platform, and music industry business. But if we look back to Spotify’s mission, it has always been upfront about its prioritisation of the fan experience in the same way it has about the artist centricity, “by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by it.”

I’m often writing from the position of both a journalist and a fangirl. And in both cases, the desire is the same: for my favourite artists to keep making and releasing new music and to make money doing so, and to improve the conditions for creativity constantly. But I also want to access their music easily, both recorded and live. With that, tension forms, and we see it playing out across streaming services whereby fans want to access their favourite artist’s music cheaply and simply.

But on the musician end of the spectrum, the days of romanticising the starving artist lifestyle are gone, and instead, we have entered a world where the creator economy is driving future tech in a way we have never seen before. While the models are still imperfect, technology like streaming is unlocking new revenue lines for artists that didn’t exist 20 years ago.

Currently, there’s also a proliferation of Web3 explorations aimed at building better conditions and infrastructures for the creator economy by putting royalties in the hands of fans, and bypassing record labels and gatekeepers altogether. But the music industry, the artists, and their fans are still very much in a Web2 world, meaning that we still look to social platforms and streaming services to connect us to the artist we love most, and the music they make.

Over the years, Spotify however, has put a significant amount of product development consciousness into the UI/UX of the platform for both fan and artist alike. As a music journalist, the discoverability of new artists and the algorithms that reward your frequent usage of the platform, have led to the finding of dozens upon of tracks I wouldn’t have otherwise heard so easily. Meanwhile, its artist development tools, analytics insights, and the discoverability channels accessible to indie musicians or podcasters is unparalleled across platforms.

Many artist teams will attest to the value of using Spotify for Artists to understand their markets, where to tour, and what songs resonate with their audience. Spotify also has offline activations like Co.Lab, a workshop and video series for professional artists and state-of-the-art studios accessible to its network of content creators, musicians and podcasters, which we toured in LA.

At Stream On, Spotify also announced a pile of new features, tools, and potential revenue lines to serve the artist ecosystem better. Chief among these, includes Spotify’s efforts in doubling down on helping creators and artist discovery with new features like ‘Smart Shuffle’, a new way to inject new music that perfectly complements an existing playlist with just the tap of a button. In addition, the platform has also introduced visual and audio previews of playlists, albums, and podcast episodes personalised to each user.

At Stream On, Spotify also announced a pile of new features, tools, and potential revenue lines to serve the artist ecosystem better. Chief among these, includes Spotify’s efforts in doubling down on helping creators and artist discovery with new features like ‘Smart Shuffle’, a new way to inject new music that perfectly complements an existing playlist with just the tap of a button. In addition, the platform has also introduced visual and audio previews of playlists, albums, and podcast episodes personalised to each user.

In an effort towards helping creators build and grow audiences with new and enhanced tools, Spotify also “showcased the next revenue line that will help artists grow: merchandise and live events.” These new concert and merchandise discovery tools are built to further connect the artist with their fans, by means of making sure concert-goers never miss another show, while letting fans buy merchandise in just a few clicks.

Meanwhile, if fans want to attend an artist's show listed on the platform, they can tap a new ‘interested’ button to save the listing to their own calendar in the Live Events Feed. Users can adjust their location and browse concerts worldwide, all personalised to their taste. These efforts also come as part of Spotify’s Fan-First programme, which includes more artists, while ensuring top listeners receive emails and notifications that give them special access to concert pre-sale and merchandise exclusives. These new features speak directly to the ongoing pressure for Spotify to add more monetisation mechanisms for creators and musicians onto the platform, while further bridging the gap between artists and fans.

Meanwhile, if fans want to attend an artist's show listed on the platform, they can tap a new ‘interested’ button to save the listing to their own calendar in the Live Events Feed. Users can adjust their location and browse concerts worldwide, all personalised to their taste. These efforts also come as part of Spotify’s Fan-First programme, which includes more artists, while ensuring top listeners receive emails and notifications that give them special access to concert pre-sale and merchandise exclusives. These new features speak directly to the ongoing pressure for Spotify to add more monetisation mechanisms for creators and musicians onto the platform, while further bridging the gap between artists and fans.

Thus the question asked by writer Cherie Hu in 2019 remains, is Spotify a consumer/fan-facing audio business or an artistic-centric one? But what I want to know is, if it is utopic to think it can be both? And if so, what kind of prioritisation does it give to the user experience, be it artist or fan? Ultimately, it is less about trying to pin one against the other; instead - what’s going on is the unfolding of an urgent discourse between what it means to make new music and the technology necessary to host and distribute it.

So I pose this question as much to myself as I do to every other fan using this or other streaming platforms to listen to music or audio content: what kind of future do we want to imagine for our artists from where we stand now, and is it possible for fans and musicians to have the best of both worlds?

- Previous Article test list 1 noise 2024-03-13

- Next Article Artist Spotlight: Xena ElShazli - Exploring Memory Through Music

Trending This Month

-

Feb 20, 2026

-

Feb 09, 2026