شهدت الفترة الأخيرة تغيرات كتيرة في مجال الموسيقى في مصر، خصوصًا بعد انتخاب المطرب مصطفى كامل رئيس لنقابة الموسيقيين. قررت النقابة إنها تتعامل مع ملف الراب والمهرجانات بشكل مختلف وتطبق شروط جديدة خاصة بالتصاريح، من أهم الشروط دي كان إنشاء شعبة "إداء صوتي" لضم مغنيين المهرجانات زي حمو بيكا، وشعبة "راب" هتضم مغنيين زي عنبة وبابلو وويجز، وفيه مغنيين هينضموا لشعبة الغناء الشعبي.

النقابة كمان قررت إن كل مغني لازم يبقى معاه فرقة موسيقية مكونة من 6 أفراد ولازم كلمات الأغاني تعدي على رقابة المصنفات وتكون فيها التزام

بقيم الأسرة المصرية.

مغنيين الراب بعد وقف عفروتو وسحب ترخيص مروان بابلو قرروا يروحوا النقابة لاجتماع مع النقيب، ويوافقوا على القرارات دي بعد منحهم مهلة لبداية ديسمبر عشان يطبقوا كل الشروط اللي أهمها الفرقة الموسيقية.

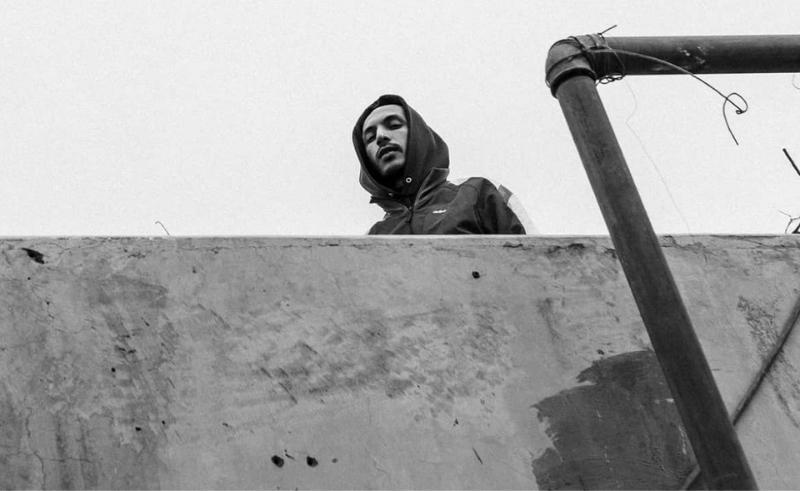

البروديوسر الموسيقي والرابر المصري "مولوتوف" اعترض على ده.

في مقابلة حصرية مع SceneNoise بيحكيلنا مولوتوف أكترعن أسباب حذفه لتراكاته مع الرابرز مروان موسى وعفروتو.

هل القرارات دي أثرت عليك بشكل مباشر؟

أثرت عليا بشكل مباشر لأني موسيقي وعازف ودي جي وبراب ومن حقي يكون عندي حرية في الحفلة بتاعتي. أنا بحاول أطور الحركة الفنية اللي اتولدت في مصر وأوصلها للعالم، وهما بيحاولوا هدم الحركة دي.

تجربتك في المعاملة مع النقابة قبل اتخاذ هذه القرارات كانت عاملة إزاي؟

لم توجه لي النقابة أي إعاقة بشكل مباشر لأني دايمًا بحاول ماحتكش بيهم أصلًا وأكون مرتبط أكتر بالشارع.

هل تعتقد أن الرقابة على كلمات الأغاني هيأثر على شكل الطرح للمواضيع الاجتماعية زي الذكورية السامة؟

اه…الذكورية مشكلة في المجتمع ولكن المنع مش بيحل أي مشكلة بل بيزيدها توتر وحل مشكلة الذكورية هو التوعية و ليس القمع.

هل تواصل معك فنانون آخرون عشان الاعتراض على القرارات؟

كتير من الفناين بيشاركوا في الاعتراض وأنا بشتغل مع مجموعة قوية في مشروع "صوت الشارع".

إيه الرسالة الموجهة من حذف شغلك مع مروان موسى وعفروتو؟

هدفي الاعتراض على الموقف بشكل قوي وتوضيح مدى غضبي وغضب الجمهورعلى اللي بيحصل وإنه لازم نقاوم القرارات الأخيرة بكل الطرق الممكنة.

ليه أزعجك أسلوب تعامل الفنانين مع النقابة؟

لأن موقفهم بشكل صريح وواضح عكس مفهوم الراب كليًا. الراب فن شارع مش محتاج نقابة وفيه ناس كثير بيحاولوا تطوير فن الراب بشكل حقيقي في مصر على عكس اللي مصممين يحولوا الفن ده لسلعة تجارية وده بييجي على حساب الفنانين وعلى حساب الموسيقي دي وتاريخها. أنا كمان معتبر ده إهانه لمصر بالذات إننا مش بلد قليلة في الراب والمهرجانات ده وعندنا تاريخ كبير جدًا…الموقف ده فضيحه قدام العالم كله.

علقت قبل كدا إن هناك حرب ضد الفن…ممكن تشرحلنا أكتر؟

دايمًا فيه حرب على الفن الحقيقي، لإن الفن الحقيقي بيكسر القيود وبيعبرعن نفسه بحرية وده مصدر الأفكار الأصلية اللي الناس بتستمتع بيها وبتحبها. الحرية هي اللي بتسمح لأنواع فن جديدة تظهر - زي المهرجانات - اللي بتكسر القيود و بتورينا أبعاد جديدة للفن والحياة. احنا بنتحارب من ناحيتين: ناحية فيها ناس بتحاول تستفيد من الفن الحقيقي ده بشكل مادي بحت فبيستغلوا الأرواح الحرة اللي بتنتج الراب والمهرجانات عشان يستفيدوا بالفلوس أو بالشهرة. ومن ناحية تانية بنتحارب من فئات في المجتمع عندها جهل وخوف تجاه أي حاجة غير مألوفة أو بتهدد مراكزهم فبيحاربونا بشراسة عان يقمعوا التغيير. بس بييجي وقت - زي اللحظة دي - و بيكون فيها ذروة الصراع…والسؤال دلوقتي هو: هل هينتصر القمع ولا المقاومة؟

ليه عايز تنشر الوعي عن الموضوع ده؟

لأن دور الفنان الحقيقي إنه يكون خادم للناس ويحس بيهم ويشاركهم كل حاجة و أنا عندي عشق لفكرة نشر الوعي وبدأت المشوار ده من زمان وعايز أكمله للآخر.

ايه الخطوة اللي جاية لمواجهة قرارات النقابة؟

في المرحلة دي لازم نطور الحركة الفنية دي من كل الجوانب، سواء كانت الموسيقى نفسها أو بداية حركة مقاومة اجتماعية وفنية قوية هدفها نشر

الوعي عن أهمية حرية الفن.

Mahraganat music has been a controversial genre in Egypt ever since its origins in the early 2010s. The genre has faced criticism over its use of lyrics and terminology that have been deemed by some to be inappropriate, and there has been an ongoing struggle for artists and performers of this genre to gain legitimacy among their peers in the music industry.

Despite these struggles, the genre has continued to grow in popularity and influence, as elements of Mahraganat have even found their way into mainstream trap, hip-hop, and electronic music. Dubbed ‘Working-Class Rap’, Mahraganat has been scrutinised by the Musicians’ Syndicate in the past. The syndicate claims that the genre doesn’t align with traditional values and ideals of society.

In October, the genre faced one of its biggest challenges yet, as newly elected Head of the Musicians Syndicate, Mostafa Kamel, announced a list of regulations that includes changing the name of the genre to ‘Vocal Performance’ and announcing that lyrics will be subject to censorship. Since then, the Musicians’ Syndicate has issued fines to rappers Marwan Pablo and Afroto, although the fines against Afroto were waived soon after. The manner in which the issue was resolved, paired with the comments made by Afroto and rapper Marwan Moussa on social media, urging fans to refrain from speaking up against the syndicate, have sparked controversy in the local music scene, as the rappers’ actions were seen to be self-serving.

In response to this series of events, Egyptian producer Molotof - one of the most vocal advocates of the genre - promptly deleted his previous collaborations with Marwan Moussa and Afroto from YouTube. In an exclusive interview with SceneNoise, the artist and producer elaborated on his reaction to the events, and on his outlook towards the situation: Scroll down to read the interview in Arabic.

How have the restrictions affected you directly?

A: As a musician, rapper and DJ, I should have the freedom to present and perform my music the way I want to. These regulations restrict my creative expression, and also undermine the artistic movement that myself and many other local artists have been building along the years, a movement that we want to share with the whole world.

What was your experience with the syndicate like before these regulations went into place?

A: The Musicians’ Syndicate hasn’t really obstructed or benefited me in the past, and I keep contact with the organisation to a minimum, as I prefer to operate in a more independent manner.

What effect do you think regulating lyrics will have on the community? Do you think it will affect social issues such as toxic masculinity?

A: Toxic masculinity is a growing problem facing society, but censorship will not resolve this issue, it will only make it more tense. The solution to this problem is awareness, not repression.

Have any other artists reached out to you in trying to spread the message of resisting these regulations?

A: Yes, there are plenty of artists who share my same feelings on the topic, and we have banded together on the project ’Soot El Share3’.

What message does deleting previous collaborations with Marwan Moussa and Afroto send?

A: I was expressing my strong disapproval of the way the situation was handled, and my actions reflect the anger that both myself and the audience felt when we saw that the rappers were complicit with the regulations.

What bothered you most about the way the artists handled the situation?

A: To be perfectly honest, the way the situation played out goes against everything rap music stands for. Rap music is the sound of the streets, the sound of the community, and it does not need a syndicate micromanaging its development. There are plenty of artists who are contributing sincere and thoughtful art in Egypt, but sadly, there are also those who approach art as a commercial endeavour. This comes at the cost of all artists, and at the cost of music and its history. Egypt has always been looked up to in the region for its artistic output and creative expression, and this situation is an embarrassment that the whole world is witnessing.

You’ve said before in a live stream that ‘this is an ongoing war against art’, could you elaborate on that statement?

A: There has always been a war against real art. Real art breaks boundaries through free expression, and it has always been the source of new and original ideas that lead the way for new forms of communication. This is what is happening with Mahraganat and other forms of contemporary music that have been pushing the limits of what is possible, by expanding our outlook on art and life in general.

The opposition to this form of art comes on two main fronts; the first comes from people who want to benefit from art in a solely materialistic way. These people exploit artists and their art for financial gain and fame. The second form of opposition stems from the fear of change that some audience members are experiencing, as music in the region has been developing rapidly, and artists have been challenging these people’s conceptions by asking them to embrace new sounds and ideas. Some people want to limit this development, and the artists’ freedom of expression by extension. In moments like these, we ask ourselves: will true art and expression overcome these limitations?

Why do you feel obligated to spread awareness on the matter?

A: Because it is the artist’s duty to serve their audience. I have started my journey of spreading awareness in my community long ago, and I intend to see it through to its conclusion.

Where does the conversation go from here? What can be done at this point?

A: Right now we are working on tackling this issue from all sides, be it through the music itself, or through the community of artists spreading awareness on the matter. We are also working with people from outside the music industry such as lawyers and journalists, and we hope to establish a solid foundation for this genre and the ideas it carries.